D. B. Cooper: The One that Got Away

November marks the 50th anniversary of one of the Pacific Northwest’s most enduring legends. Ripe with home-grown weirdness, this tale is as uniquely us as Bigfoot and the flying disc around McMinnville. For some longtime locals, its details are as familiar as a family history.

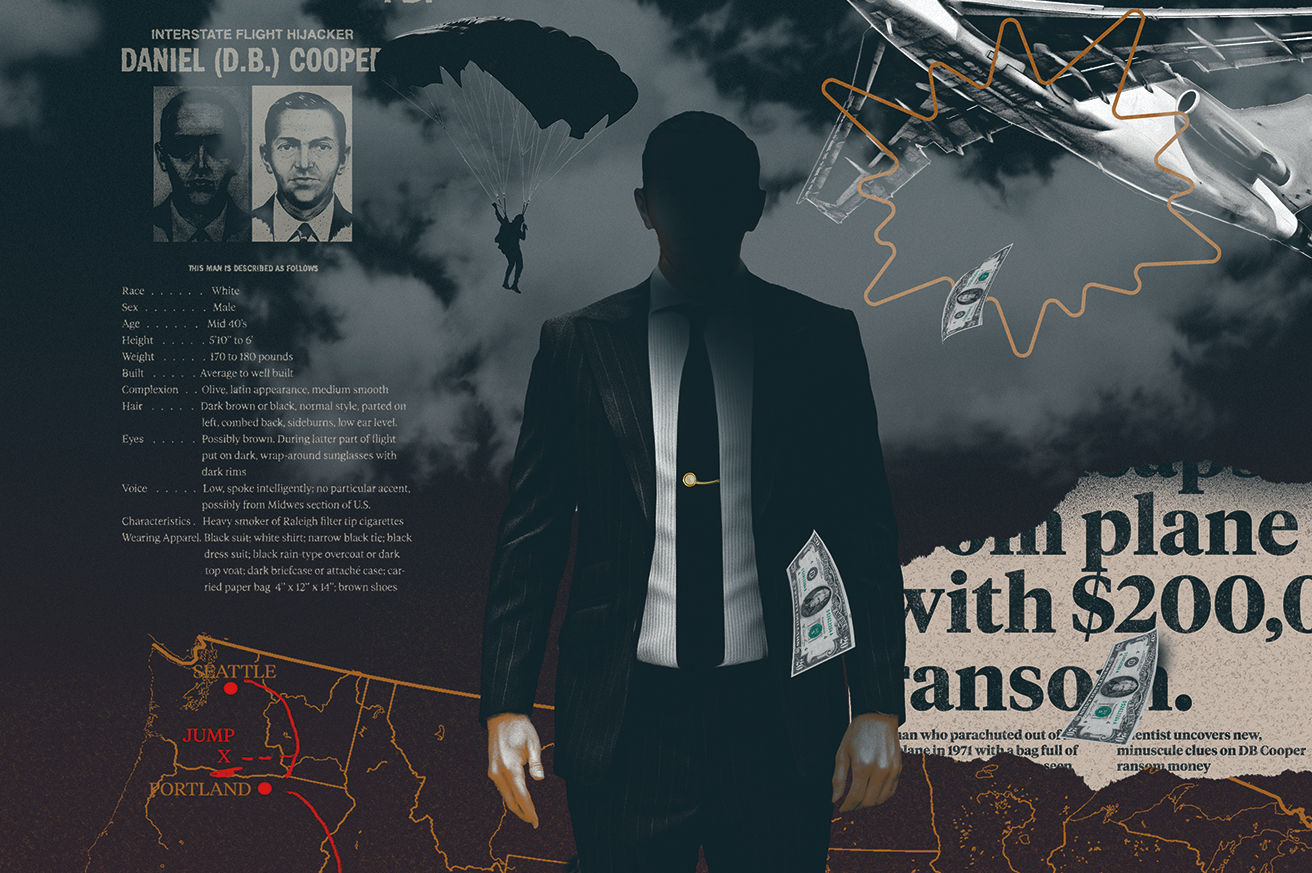

What we know: on November 24, 1971, a man identified as D. B. Cooper jumped from a Northwest Orient Airlines plane with $200,000. What we don’t know: what the hell happened after. It remains the only unsolved case of air piracy in US history. And it begins at our beloved PDX.

“Maybe you can get him into down towards Portland; he might get homesick and want to land there, I don’t know.” —Ground control to NW 305 pilot

On a Wednesday afternoon, the day before Thanksgiving in 1971, a man boarded a Boeing 727 in Portland. “That’s a 727, isn’t it?” he asked as he paid for a one-way ticket to Seattle with a $20 bill. When the ticket agent asked his name, the man paused slightly and said, “Cooper. Dan Cooper.” A reporter later fumbled their notes and the name “D. B. Cooper” was born.

The suspect has been described as “compactly built in a dark business suit” and “calm, Latin looking.” The flight crew radioed that he was six-foot-one-inch, had black hair, and was roughly 50 years old. Passengers described a man with an athletic build, dark brown eyes, and a “swarthy complexion.” Some said he had marcelled hair. Wearing dark, wraparound glasses, he checked no luggage and carried only an attaché case and a brown paper bag. In short, D. B. Cooper presented like a long-lost triplet of Jake and Elwood Blues.

As Flight 305 took off, Cooper was observed and later recalled by some of the passengers. Still in his sunglasses, he chain-smoked Raleigh cigarettes. Details differ, but some recall he ordered a bourbon and 7-Up, and paid for his cocktail with another $20 bill.

Cooper sat, sipped his cocktail, looked out the window, and handed a flight attendant a note as she passed. She pocketed the slip, thinking it was just another example of the come-ons traveling salesmen were handing her all the time. But Cooper insisted she look at it, and when she did, she read the scrawled message: “I have a bomb. Sit by me.”

One of the flight attendants, Tina Mucklow, came to sit beside him. The hijacker calmly commanded her to write out his demands for another flight attendant to deliver to the captain of the plane. His asks were $200,000 in American currency, a knapsack with straps, and parachutes. He also stated that he had a bomb in his briefcase and was ready to use it. To dramatic effect, he opened his briefcase to display eight “red cylinders, a battery, and a tangle of wires.” When Mucklow asked the hijacker about his motivation, and whether Cooper had a grudge against Northwest Orient (as Northwest Airlines was then known), he replied: “I don’t have a grudge against your airline, Miss. I just have a grudge.”

The 727 flew north and eventually entered a holding pattern near Seattle, at about 4 p.m. The plane circled the city for over two hours as the ground crew gathered Cooper’s demands. Flight 305’s captain, William Scott, used the intercom to tell the passengers there was a minor mechanical issue, and the plane needed to burn off some fuel before they landed. Meanwhile Cooper, who was said to have remained calm and circumspect all the while, communicated almost exclusively with Mucklow. She said that “he was not nervous. He seemed rather nice ... and he was never cruel or nasty.” At one point he looked out the window and said, “That looks like Tacoma down there,” indicating he may have spent some time in the Pacific Northwest.

Eventually the plane landed at Sea-Tac and taxied to a secluded but well-lit section of runway, all passengers still on board. Now the hijacker changed his demands, asking for four parachutes—two front and two back—and for the plane to be refueled. And he wanted “no funny stuff.”

As the airline and law enforcement prepared Cooper’s cash, every bill was all run through a Recordak machine, so every serial number was copied. The 10,000 $20 bills weighed more than 20 pounds. When the money was dropped off on the tarmac, and Mucklow took the bag back to the hijacker, it was heavy enough that she had to drag it on the cabin floor behind her like so much dirty laundry.

“He’s indicated that he wants the show on the road, so we’re going to get her cranked up here....” —Pilot

The skyjacker told the crew he wanted to travel to Mexico City, offering Benzadrine pills (bennies or speed) he claimed to have in his pocket if the crew got sleepy during the long flight. He instructed the flight crew to “fly with the landing gear down, flaps at 15 degrees, and the rear stairway lowered.” (Called the airstair or aftstair, this set of stairs built into the rear of the plane so passengers may board or alight without a jetway is a signature feature of the Boeing 727.) The flight crew was to keep the airplane at 10,000 feet, and no higher.

Copilot Bob Radaczak told Cooper that the plane couldn’t take off with the airstair open. “Fine,” Cooper said, “then I’ll keep one of the girls back here after we take off.” Refueling delays made the hijacker uneasy, and he called the cabin demanding to “get this show on the road!” Eventually the plane was fueled and two Navy Back 6 military-issue parachutes and two Pioneer sport chutes were brought aboard, along with the money. Cooper released the passengers and two of the flight attendants. As they disembarked, most of the 36 other passengers had no idea the plane had just been hijacked. After the incident, even Ralph Himmelsbach, the FBI special agent who worked the case, conceded that “no one was unduly upset because of the ordeal.” Flight 305 departed Seattle at 7:37 p.m., heading south.

Cooper seemed to know quite a bit about the 727, but he didn’t know how to lower the airstair, so he had Mucklow show him. He did, however, refuse printed instructions on how to use a parachute: “I don’t need that.” He also told Mucklow that he knew where the oxygen was kept and that he would get it himself if he needed.

The hijacker sent Mucklow forward and ordered her to draw the curtain between economy and first class. As she was closing the curtain, she caught a glimpse of Cooper tying something like rope around his waist. At 8:05 p.m., the flight crew checked in over the intercom, and the hijacker said there was nothing else he needed from them. That was the last known contact between Cooper and the rest of the world. Then an indicator light on the control panel signaled that the airstair was fully extended.

At 8:12 p.m. the crew radioed, “We’re getting pressure oscillations in the cabin. He must be doing something with the stairs.” Flight 305 was paralleling Interstate 5, flying over the Cascade Mountains.

The plane was moving at 200 knots, at 10,000 feet, and the outside air temperature was minus 7 degrees Celsius. When the plane landed in Reno, Nevada, for a refueling stop, the lowered airstair banged on the tarmac, releasing sparks. Cooper was no longer in the cabin.

“Is everything OK back there? Anything we can do for you?” —Flight crew, 8:05 p.m. “NO!” —The hijacker’s emphatic reply, and the last known contact anyone had with D. B. Cooper

Most investigators believe Cooper jumped around Ariel, Washington, northeast of Woodland, and the Columbia River.

In his thin business suit, raincoat, and loafers, was he really equipped to handle such a jump? Did he have long underwear on underneath? What else was in the attaché case, under what looked like highway flares he staged as a bomb? Jump boots? A wrist altimeter? Were the flares a part of his caper, perhaps to signal for an extraction? One passenger saw Cooper emerge from the lavatory with a four-inch-tall light-colored bag, maybe burlap. He had something else with him—its contents have never been discovered.

Cooper’s timing was impeccable. It was the day before Thanksgiving, the perfect time to explain an absence from any work duties. It leaves five full days to hijack an airplane, collect a ransom, get out of the woods, stash the loot, head back home—and still make it back to your desk by Monday morning, to all appearances like any average schmuck who never did nothing about their grudge their whole goddamned life.

Cooper was never found. The FBI conducted a massive search in the rugged and thorny presumed drop zone, but neither Cooper’s body nor parachute was ever discovered. The search was so exhaustive that it even turned up two bodies the authorities weren’t looking for: a missing, murdered woman at the bottom of a cistern and an injured hunter who had died in the woods.

But a pittance of Cooper’s ill-gotten fortune was found. On Sunday, February 10, 1980, more than eight years after the hijacking, a young boy named Brian Ingram and his cousins were playing in the sand on Tena Bar on the Columbia River, about nine miles downstream of Vancouver, when Brian found some $20 bills. Two hundred and ninety of them, in fact. All of the serial numbers matched Cooper’s cache. Was the money buried near there? Had it washed downstream through the vast Columbia River watershed? To date, that’s the only money that has turned up from the heist.

In our collective imagination, in our legend, Cooper exists for just a few hours. A man named Dan shows up at the airport in Portland, buys a ticket, gets the cash and chutes in Seattle, and then jumps out of the airplane over the Cascades on a cold, windy night. But in that short time period, he built 50 years and counting of theory, conjecture, and fantasy. His is a story we own, one chock-full of individualism and opportunity; a single person, well-mannered and bourbon-sipping, brazenly vaulting into the wilds of nature and maybe, just maybe, getting away with it.

Half a century on, D. B. Cooper is a pop culture figure of iconic proportions. The black suit and tie, the sunglasses, the invented detail of jumping from an airplane with an actual briefcase in hand. The FBI sketch, featuring a suspect looking remarkably like Bob Hope. His likeness, the mystery, the shades, all have contributed to our fascination with this tale. The filmed-in-Portland TNT show Leverage had an episode about the Cooper caper. David Lynch used the name as inspiration for FBI Agent Dale Bartholomew Cooper on the Northwest-set Twin Peaks. The hijacker has been a plot element on other shows, too, from ’90s sitcom Newsradio to 2021 Marvel series Loki.

In 2016, the FBI ended its active investigation, a move that in itself just feeds the mystery. It seems if D. B. Cooper did survive his jump into darkness, into legend, that he indeed got away. Unlike other Northwest legends, most of us know we’ve never had a run-in with Bigfoot or a UFO, but any of us could have bumped into D. B. Cooper.

Whether he lived or not is almost immaterial.

Want to dig deeper? Here's a roundup of further reading, listening, and viewing on D. B. Cooper.