Inside the Search for Hundreds of Portland’s Missing Students

The voice on the other end of Taneisha Manning-Granville’s phone sounded small, and very far away.

At 1:30 in the afternoon on a weekday, the student on the line should have been in school. In fact, up until a few days ago, she was back in the classroom after a long absence, the start of a success story.

Then, tragedy: the sudden, unexpected death of her sister’s 2-year-old son brought the return of turmoil after a brief foray into routine. Suddenly, she was back at home, asking Manning-Granville to come to the memorial service and to please share the GoFundMe the family had set up for funeral expenses, because they needed help, now. There was no talk of coming back to school.

“I’m not even going to pretend there are words,” Manning-Granville says over the phone. “There are none.”

Manning-Granville, who has been in her job since 2018, is one of six outreach coordinators on the Portland Public Schools’ Reconnection Services team. They are all part caseworker, part detective. Their weapon of choice is their phones, because kids reply to texts and parents will sometimes listen to their voicemails. They spend their days trying to find answers to a question that the pandemic has laid even more bare: where are all the kids?

Taneisha Manning-Granville spends hours on her phone each day, trying to connect with kids who should be in school (and their parents). Kids reply to her texts, sometimes, while their parents might be more likely to listen to her voicemails.

Image: NASHCO PHOTO

Public school districts across the country have long been grappling with lost teens. Depressingly and predictably, students of color, those who live in poverty, and those with special needs are overrepresented in the population of those who give up or get pushed out. Historically, they’ve left for many reasons: they were bullied or their home lives were unstable, they struggled with homelessness, addiction and/or mental health, they got behind in school and despaired of catching up, or the need for a paycheck from full-time work took precedence over education.

Over the past two years of isolation and uncertainty, all those factors got turned up to 11—and fear of catching and transmitting COVID-19 was added to the list.

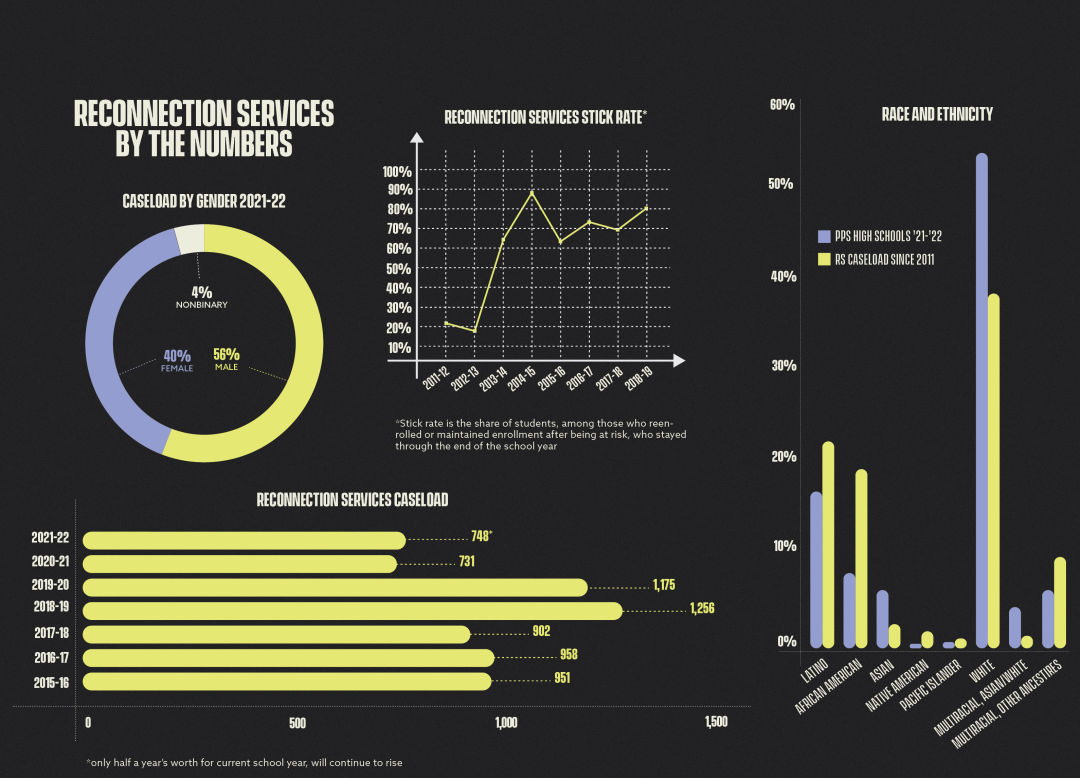

Here in Portland, 1,256 students were flagged to Reconnection Services in the 2018–2019 school year, mostly all high schoolers, with a smattering of middle schoolers. Perhaps surprisingly, the number of referrals shrank during the spring of 2020, and then contracted further, to just 731 in the disrupted school year of 2020–2021.

But that dip was not because there weren’t kids slipping through the proverbial cracks—it was because no one was around to see them fall.

Since the start of this school year, the number of students referred to Reconnection Services has been growing once again, reaching a caseload of 746 by the end of January. Some of the absences were easily tracked down and explained—the children had transferred to another school district and records hadn’t been processed, or to a private alternative, or they were home-schooling, says Manning-Granville. Case closed.

But others—hundreds of Portland’s teenagers—simply vanished.

The members of the Reconnection Services team gather for a group photograph. Each staff member is responsible for a different geographic area of the city, or for kids who are back at school after being in rehab.

Image: NASHCO PHOTO

Decades of research shows that kids who don’t graduate from high school carry the consequences for the rest of their lives, via persistent job and home instability, says Megan Kuhfeld, a researcher at the Portland-based educational nonprofit NWEA (formerly the Northwest Evaluation Association) who has been tracking the nascent effects of remote school on academic achievement.

From a research perspective, Kuhfeld says, the kids who should be in school but are not “are the hardest to understand the impacts [of the pandemic] on. In our data, they are just missing.” But previous studies on chronically absent students offer some hints, she says: there’s a direct line between how much school students miss and performance on tests and other academic measurements.

Ordinarily, if a kid doesn’t show up to class for 10 days in a row, they’re flagged in the system, triggering outreach from attendance coaches, school counselors, and teachers. During the pandemic, in an effort to give grace to parents and students coping with constant uncertainty, Oregon temporarily suspended its “10-day drop” rule. The kids having trouble staying in school were largely on their own.

Some, like Djinn Lindsay, 16, who has attended both Franklin and McDaniel High Schools, struggled to focus on the disembodied voices and black squares of his teachers and classmates on the screen in front of him, and wound up failing nearly all of his classes in distance learning, a mountain that felt impossible to start climbing again. His mother, a single parent whose job working security at events evaporated during the pandemic, was busy trying to help his two younger siblings; she didn’t realize her eldest was slipping away until it was almost too late.

Nikki Ortiz struggled with online school during the pandemic; finding a quiet place to work was a challenge, with so many younger siblings at home.

Image: NASHCO PHOTO

Some, like Nikki Ortiz, who was living in Camas, Washington, during most of the pandemic but has since moved to Portland after her parents’ divorce, struggled with a reliable Wi-Fi connection and younger siblings who needed help with their own online school. Her grades, once mostly As and Bs, turned into a string of Fs. Online school gave her “a lot of reasons to disconnect and withdraw into myself,” she says.

Some, like Dex Cross, 17, actually preferred an online format, after years of trying to acclimate to school as a nonbinary kid who once scuffled with campus security over being allowed to use the bathroom of their choice at their Hillsboro school. But the endless hours at home took a toll, leading to family breakdowns, until finally Cross left home. They slept outside and at shelters for a while, until caseworkers helped them get into transitional housing and start filing for legal emancipation. The logistics ate up hours; school felt out of reach.

Some, like Zyeira Price, 19, who has bounced between the David Douglas and Portland school districts, took full-time jobs—first, providing in-home care to Alzheimer’s and dementia patients after watching a training video or two, then working in a gift shop at the Portland International Airport, and finally landing at the Cinnabon at Lloyd Center. Schoolwork was the last thing on her mind.

Zyeira Price took a job during the pandemic, and moved in with her boyfriend. School was not at the top of her priority list.

Image: NASHCO PHOTO

Price is just the kind of student Manning-Granville and her colleagues worry over. Even prepandemic, she was likeliest to turn up on their case list: a student unlikely to see the relevance of school. Around the end of middle school Price’s mother died from a sudden illness, leaving her and different combinations of her four siblings to bounce between family homes, from an uncle’s house to an aunt’s, her father’s home to her sister’s mom’s. Eventually, she landed at Madison High School (now called McDaniel), where all that kept her engaged was the cheer squad. A car accident set her into a spiral—skipping school, having sex, she says. When school moved online during the pandemic, it was easier than ever to give up, so she did.

“When you’re just in your own environment, you’re way lazier than you would be if you were in a school building,” she says. “I started working a lot, and school just fell through the cracks.”

Elise Huggins, who supervises the Reconnection Services team, says she thinks the true number of middle and high school kids who went missing from the school system during the pandemic is still unknown.

Complicating matters, a change in funding targeted at lower-income students led the district to briefly consider cutting the program’s staffing last summer, despite having nearly $74 million in federal funds designed specifically to combat COVID-related learning loss, on top of a $762 million operating budget.

That $74 million is use-it-or-lose-it by 2024, and in Portland the district’s plans call for spending roughly a third of it—about $24 million—in the current school year. But only $2.4 million is earmarked expressly for this particularly vulnerable group of kids, set aside for “student re-engagement and racial equity and social justice partnerships” with cultural organizations like the Latino Network. Another $8.5 million in spending on tutoring, summer programming, credit recovery, and technology investments indirectly supports this population, Huggins says. The bulk of the rest was dedicated to setting up the district’s K–12 online school offering, charter schools, and professional development for educators. And some of the money remains unspent, a district spokeswoman says, as some departments within PPS are using less of the funds than planned for.

Kuhfeld and other researchers say there’s a strong argument to be made that the federal COVID emergency relief dollars should be laser-concentrated on the most vulnerable, on whom the pandemic’s burdens landed the hardest. Huggins can imagine what that would look like. Doubling her staff and spreading out caseloads accordingly would let Reconnection specialists support this impacted generation of kids for longer, advocating for them through graduation, she says. Earmarking more of the emergency funding could allow for expanded mental health supports, or offering families help with housing and food insecurity, to give students the space they need to focus on school.

And in the wake of the pandemic, middle school Reconnection Services referrals are going up, Huggins points out, but the district hasn’t made deep investments in alternative options for that age group.

To its credit, Portland Public Schools has spent years investing in solutions for high schoolers for whom the system has failed: alternative schools, treatment therapy programs, night school classes to support workday schedules, teen pregnancy supports, online programs for those who might thrive there. Prepandemic, there were signs that those efforts were paying off. In 2011, when the Reconnection team got its start, only 22 percent of the students in their caseload wound up back in school. By the 2018–2019 school year, that number was at a much more promising 81 percent.

But data collection was suspended in 2019–2020, and the trail goes darker.

Now, Manning-Granville says, “Kids are questioning the path we have given them. They’re dealing with the fatigue of educational expectations. Jobs are available, and they know it. I see where they are living and how they are living. It’s understandable.”

On a relentlessly rainy November day, Manning-Granville shows up at one of the high schools in her territory, Roosevelt in North Portland, for a meeting with a school counselor, a student who missed months of school, and his father, to talk about his reenrollment. The text messages come in rapid succession: The boy and his father are headed to catch a bus. No, they missed that bus. Now they won’t be coming after all. Maybe next week.

There are lots of frustrating missed connections like this one. For every few families an outreach coordinator can manage to reach, there's one who doesn't reply to calls and messages and postcards (“I never get anyone to call me back from the postcard,” says Sharde Dennis, one of Manning-Granville’s colleagues) or show up for home visits and scheduled Starbucks meet-ups. Every attempt at contact is painstakingly recorded, to create a paper trail. The Reconnection team never finishes. There are always more kids. The job is demanding; the average tenure of the current staff is about four years.

Social studies teacher Catherine Volponi consults one-on-one with a student at Alliance High School at Meek.

Image: NASHCO PHOTO

When they do get through, there’s a long list of boxes to check. Does the student speak English as a second language? Are they in need of special education services? A safety plan? Have they been expelled from a neighborhood school, are they pregnant, have they been in the juvenile justice system, is there an open Department of Human Services file on them, do they need mental health support, are they known to have a gang affiliation, how many credits do they need to graduate?

There are little successes to get Manning-Granville through the day, and kids who stick with her, like the one whose mother once met her at the Burgerville by Parkrose High School and poured out her heart. The boy went back into school for a while and then got into some trouble. He recently called from jail to say he wanted to try again when he was released, this time for real. Manning-Granville has attended summer school graduations, pulled over when she sees school-age kids out on the street during the weekday, stays up at night worrying over the kids she calls her babies.

Even once kids do return to school, they are fragile. Take Lindsay, who’d slipped into a video game fever dream during remote school, while tasked with keeping his younger brother, who started kindergarten in 2019 and is now in second grade, on task. Prepandemic, his motivation was already low, his mother said—the only subject that kept his interest at Franklin High was robotics. The pandemic brought a new set of challenges and family upheaval, including his now eighth-grade sister moving out to live with extended family, and Lindsay got progressively more anxious. He didn’t drop out of school, says his mother, Alexandria Roberts, so much as stop showing up.

At a automotive class at Alliance High School at Meek, the focus is on hands-on learning and practical skills.

Image: NASHCO PHOTO

Eventually, they were referred to Reconnection Services, and Lindsay got started in early winter at Alliance High in the old Meek Elementary building in Northeast Portland, one of several alternative programs for kids who’ve struggled at conventional high schools in Portland. Alliance has small classes, hands-on learning, and extra supports for a high-needs student body. Lindsay is finding his way, he says, but there are still days when he doesn’t show up there, either, needing the space for mental health breaks.

Lindsay’s not alone—teachers at Alliance, where new students are consistently incoming as they plug back into the school system, say their students needed to relearn how to be in school this year after so long outside of a school building.

At Alliance at Meek, students’ phones are never far away, even during class time.

Image: NASHCO PHOTO

In classrooms, kids keep their phones out and close by at all times, like security blankets. To break through to them, the school’s teachers get creative, seeking out projects aimed at reeling in those who are prone to disengage. In the fall, Jerry Eaton, a revered shop educator, led a group of students through the design/build of a tiny house that was donated to a Catholic nonprofit for homeless housing; when a robotics program began to prove prohibitively expensive, Eaton pivoted to teaching students to build and fly their own drones. Kids know that the attendance coach and social workers are stocked with incentives, from Burgerville gift certificates to hair-braiding sessions.

Dex Cross is hoping to attend in-person classes at Portland State next fall.

Image: NASHCO PHOTO

The Reconnection coordinators come by regularly, too, at Alliance and at other schools, to check on students they’ve helped plug back into school, in hopes they won’t wind up back on their lists. The kids who’ve benefitted from such support say it has made a difference.

Dex Cross is now settled in transitional housing, has a job at Chipotle, spent the winter holidays with their family, is back in online school, and will attend Portland State next year. After all this time, they’re finally feeling safe enough in their own skin to be back in person, Cross says.

Roxane, a sophomore at Alliance whose last name is being withheld to protect her privacy, says she counts on the staff there to help her do her best and set boundaries, after years spent in different foster homes and a stint in a rehab facility for depression. Her favorite class, she says, is her ethnic studies course: “It’s a discussion-based class—and Miss Ursula doesn’t tolerate any negative behavior,” she says.

An Alliance at Meek student who says she’s finally feeling safe and supported at school.

Image: NASHCO PHOTO

Nikki Ortiz, who struggled so hard to focus in remote school amid the din of her siblings and unreliable Wi-Fi, also points to school mental health specialists as helping her stick it out at an Alliance campus now that she is back in school; she’s hoping to go to Portland Community College afterward. “I remember going home one day after talking with one of my counselors,” she says, “and I didn’t feel immediate, awful dread for everything in life. I didn’t know counselors could be so ... upboosting. It was a shift for me.”