The Rock that Brings the Runners

People leave all kinds of tributes at Pre's Rock in Eugene

Image: Charles Butler

Yesi Silva had big plans for a recent Saturday morning in Eugene with her fiancé Colton Hanson. They were going to visit … a rock.

Yep, a rock.

But it wasn’t just any rock. In fact, it’s more of a boulder, jutting out of Judkins Point, about a mile from the University of Oregon campus. It’s canopied by Douglas firs and coated, in parts, with poison oak.

You might think the toxic vines would keep people from getting too close. They don’t. The rock lures people like Yesi Silva. Some come to see it or touch it or even talk to it. It’s been that way for the past 47 years, ever since its namesake, Oregon’s most legendary runner, Steve Prefontaine, tragically died there when he was just 24. Now, Pre’s Rock is adorned with artifacts—running shoes, race bibs, a half-filled beer mug, and even hand-written notes to Pre—that reveal visitors’ fandom and reverence.

“It qualifies for some as a shrine. For some, it’s a place of pilgrimage where you can connect between the living and the dead,” says Daniel Wojcik, a UO professor of English and Folklore Studies who has interviewed visitors pilgrimaging to the rock over the years, recording their motivations for coming.

And it’s a site that is expected to see even more pilgrims in the coming days. Starting Friday, July 15, and running through July 24, the shiny new Hayward Field on the UO campus will host the World Athletics Championships, the first time that the mega track-and-field meet, with 2,000 athletes and upwards of 20,000 visitors, will take place in the United States. Between race sessions, many of those visitors are likely to head to Pre’s Rock.

Yesi Silva and Colton Hanson at Pre's Rock.

Image: Charles Butler

Silva and Hanson, who live in Keizer, made their visit during the USA Track and Field Championships in June, the contest that decided which athletes would make the American team competing at Worlds. With a few hours before the day’s first event, Silva, 27, had suggested that they head to Skyline Boulevard in Eugene’s Fairmount neighborhood and see the rock she had known about for years, but never visited. Hanson, 28, agreed, even though his bucket list had never included View rock memorializing deceased runner. Nodding toward Silva, a competitive distance runner at BYU, he says with a laugh, “She runs to get in running shape. I run to get in shape.”

But why did Silva need to see it? Two decades separated her birth from when Prefontaine—the gritty, charismatic runner from blue-collar Coos Bay, Oregon, who rose to American and world stardom on the track in the early 1970’s—died when his car overturned while coming down the serpentine Skyline one evening in May 1975. Silva hadn't heard of the runner until she got to junior college.

But then a coach introduced her to his legacy (eight American records at the time of his death; a memorable Olympic race in 1972) and his run-far/run-hard tenacity. She subsequently watched grainy black-and-white YouTube videos of Pre. She ran on Eugene’s popular Pre’s Trail during previous visits. She read through the collection of Pre quotes—"Somebody may beat me, but they are going to have to bleed to do it;” "To give anything less than your best is to sacrifice the gift."—that have become mantras for generations of high school runners. Like many before her and since, she became Pre-conditioned.

“I think more than anything it’s his principles and his work ethic. He is a running icon, really for anyone,” Silva says as she stood next to the Rock for the first time. And as she examined the site, which includes a permanent black stone slab dedicated to the memory of Prefontaine along with mementos left by previous visitors, she said she came away with an understanding that went beyond running. “It’s amazing how short life is,” she says, “but it is amazing the opportunity we do have to enjoy the time that we have.”

Scott Shepley of Portland brought his daughter to Pre's Rock

Image: Charles Butler

As Silva and Hanson left, a 64-year-old runner from Massachusetts arrived. Then a family from Rochester, New York, and a husband and wife from Walla Walla, Washington. Then a dad from Portland with his young daughter; he was making his fifth visit, she her first. Why come back so often? “It is paying respect,” says Scott Shepley, 43, who like Prefontaine ran middle-distance events while in high school. “[Prefontaine] gave a voice to all athletes. It is so inspiring, everything he did, the way he lived his life.” Then, looking at his daughter roaming near the Rock, Shepley says the Prefontaine style has “bled over into the way I try to raise my kid. She is into swimming right now, but she does have some of [Prefontaine’s] qualities as well.”

On this visit, Shepley saw something different. Previously, visitors needed to stand in the road to get a close look at the memorial. But this winter a sidewalk and a black metal guardrail were installed in front of the boulder. These are among the updates the City of Eugene Parks and Open Space department did to make the site safer in anticipation of increased traffic this month. Eugene has been preparing for the World Championships since it was awarded the meet in 2015. In that time, hotels have been built, new restaurants opened, and, of course, a $270-million, Phil Knight-funded stadium constructed. But resources and planning also went toward this spot off-the-beaten path.

“It was a light touch,” Emily Proudfoot says of the renovations to the space, “but it is a really nice way to create a safe space for people to come and visit.” Proudfoot is the principal landscape architect for Parks and Open Space, the department that maintains Pre’s Rock. She acknowledged that the Rock is an outlier for her team. “It is … sort of a strange place. We don’t typically memorialize people where they die, right? As a culture we memorialize people typically in a cemetery or a memorial garden,” Proudfoot said. She paused before adding, “I just think it’s awkward to memorialize someone where they died.”

She’ll get no argument from Linda Prefontaine. The runner’s sister said her brother’s death site had become a “marketing tool” used to attract visitors to Eugene. She has heard of groups being bussed to the site and worries that it has turned into “a circus.” She no longer visits. “That is where he took his last breath. That is not a happy place, not for me,” said Linda Prefontaine, who still lives in Coos Bay, her family’s hometown. “It doesn’t bring me any pleasure to go there. That’s where he died.”

In May, Linda Prefontaine caught a screening of “The Church of Pre” (wider distribution plans are still in the works) and got a better understanding of what can entice people to the Rock (beyond marketing gimmickry). The soon-to-be released documentary film traces the history of the memorial and the motivations of some who have sought it out. In the film, Linda recalled, “a professor was talking about why people are attracted to places like [Pre’s Rock]. There are places all over the world where people go to and visit. And there have been studies done on what that does do for people when they go.” For some, she learned, a visit can heal a pain or satisfy a curiosity. “There are,” she said, “all kinds of answers.”

Case in point: Three years ago, Ku Stevens made his first visit to Pre’s Rock. At the time he was a high school freshman living in a small Nevada town (Yerington, pop: 3,190). But he had a big dream: to run for the University of Oregon. He had first started researching the school and its track history when he was in sixth grade. He read about Prefontaine and his coaches and set about a plan to get recruited to the school. By the time he finished his senior year, he was a state cross-country and 1600-meter champion.

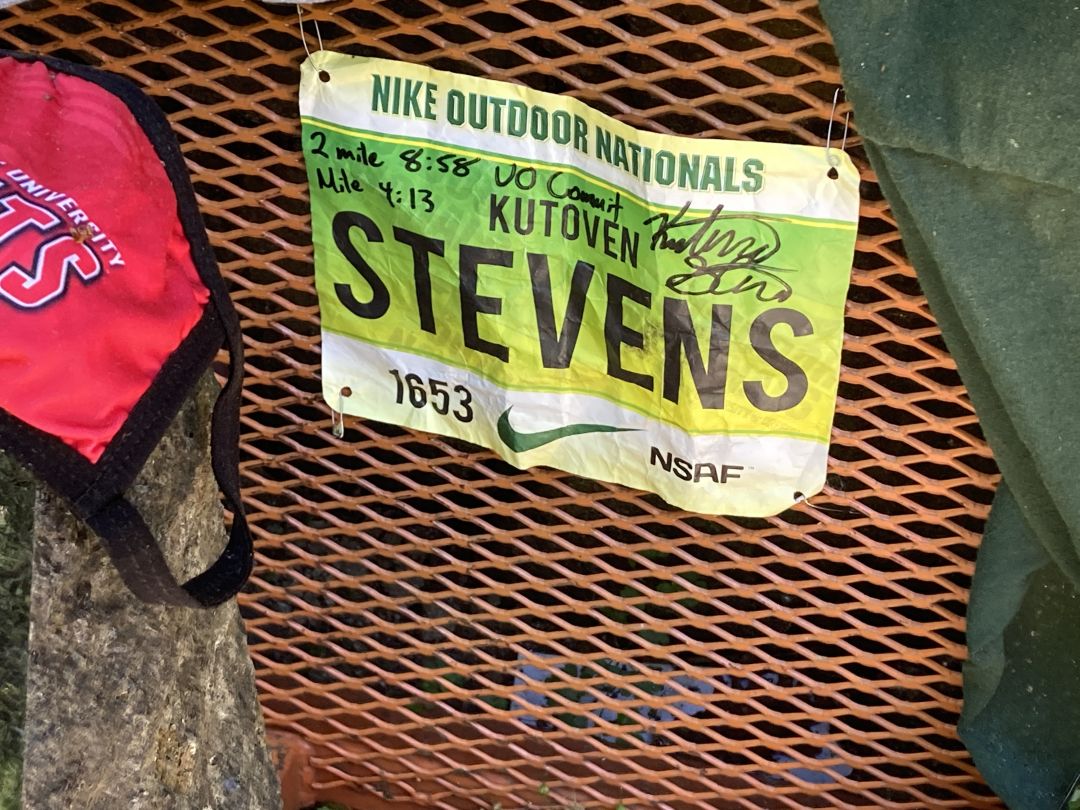

Ku Stevens, a UO track commit, left his bib at Pre's Rock.

Image: Charles Butler

This spring, he returned to Eugene to compete in a high school meet at Hayward Field. He placed fifth in the two-mile and 18th in the one-mile, but wasn’t satisfied. Later, he ran up to the Rock. He was alone. He took his race bib, and scribbled his name, his events, his times, and a message: UO Commit. He placed the bib near the Rock, and then talked to the Rock: “Hey, what’s up? Here you go. Here’s my bib. This is how I did.”

He waited a moment. “I could have done a lot better.”

And then Ky Stevens ran off.