Notes on Answering the Call to Substitute Teach in a Portland Middle School

On my first day as a substitute teacher, a strikingly blue-eyed eighth grader in an oversized Blazers jersey—I’ll call him C—blew up a condom and batted it around like a balloon while his friend made sexual innuendos sotto voce. “Isn’t that saaatisfying? I feel sooo satisfied.” D, for whom English is a second language, wedged himself into a cabinet. Kids who belonged in the class, as well as several who didn’t, kept walking in and out of the room, and nonstop talking drowned out the science video I was projecting. When the fire alarm rang and my job quickly became getting a classroom full of masked eighth-grade strangers down to an assembly point on the field, C—condomless now—said to me, with gently mocking suavity, “Don’t you worry, mommy.”

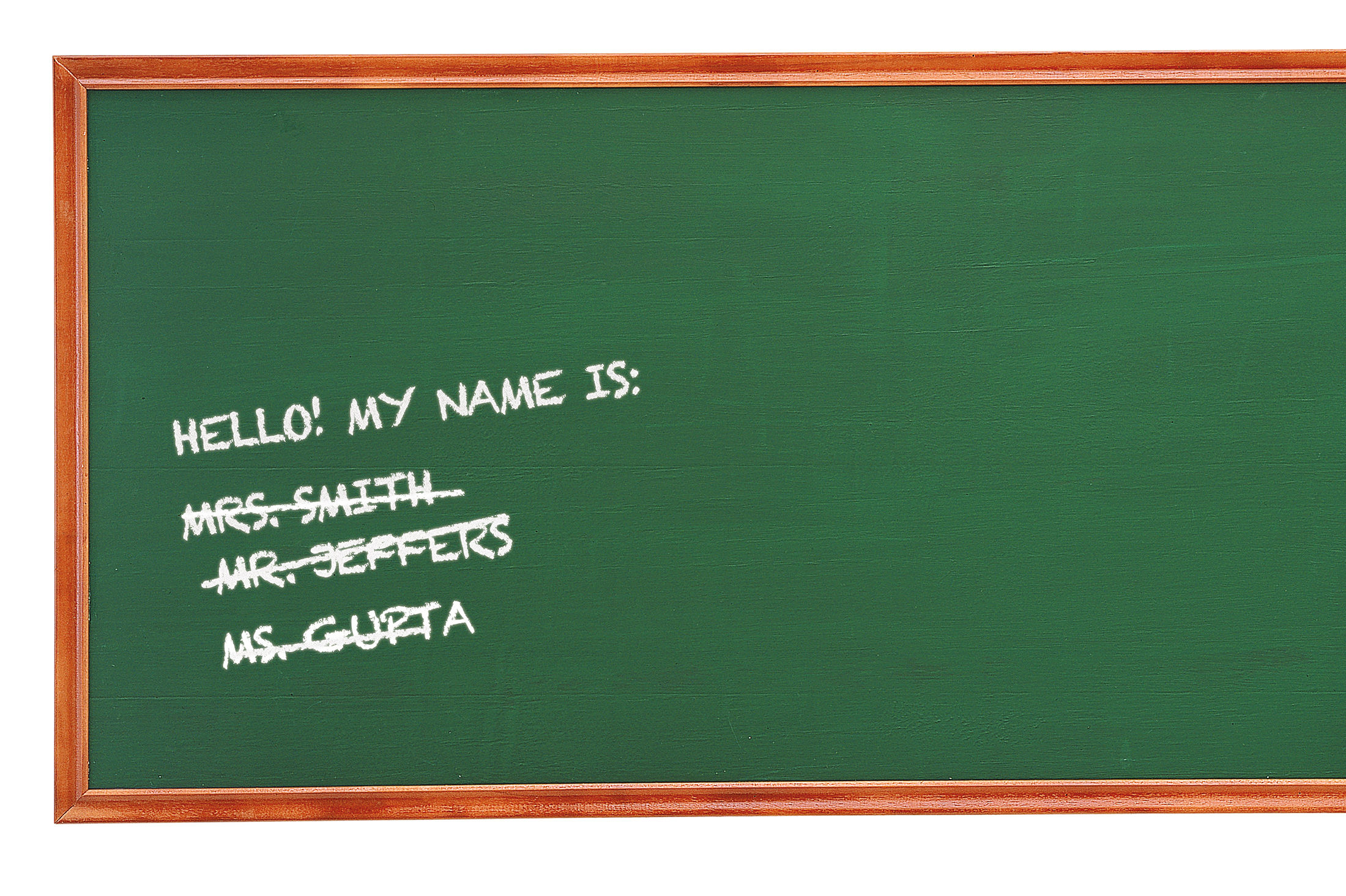

I decided to become an emergency substitute in January 2022, after reading about sick and overwhelmed teachers and an extreme shortage of subs throughout the state. My job as a writer meant long but flexible hours, and though my teaching certificate expired ages ago, I wouldn’t actually need one: in the fall of 2021, Oregon’s Teacher Standards and Practices Commission had announced any adult of “good moral character” could apply for a restricted substitute teaching license.

Apply I did—and with admirable efficiency, Portland Public Schools screened me, interviewed me, and recommended me for hire. After passing a background check and completing the required online training, I was qualified to substitute. But this is very different from saying that I was prepared.

On that first day, it seemed like everything that could go wrong did. By the time the bell rang at 3:45, stress had locked my jaw; I could barely open my mouth. Later, when I tried to describe the day to my family, tears started streaming down my face. “I’m not sad,” I insisted to my daughters, students at a different PPS middle school. “I don’t even know why I’m crying.” As tough as those kids were, I’d found many of them hilarious. Charming, even, in their reckless adolescent ways.

Don’t you worry, mommy.

PPS offers substitutes incentive pay of $50 extra per day to take assignments at 23 harder-to-staff schools in the district. Some of these schools, including the one I went to, were also approved to hire additional, free-floating subs to cover any unfilled positions. And so, because my next three subbing days were better than my first (and because a sweet sixth grader gave me a beautiful origami crane, and a rowdy seventh grader told me she was trying so hard to be good, and because the exceptionally dedicated school secretary asked me to), I became the school’s regular Wednesday “guest teacher.”

Besides language arts, which I’d taught full-time 25 years ago, I covered classes in dance, PE, health, and social studies. On the rare days there were no unfilled positions, I did lunch duty and cafeteria cleanup, processed yearbook orders, or organized office supplies in the storage room. I wanted to become a familiar face in the hallways, so I always wore a striped shirt. More important, I always handed out candy. (Two pounds of Sour Patch Kids and six pounds of Jolly Ranchers by June.)

I loved talking to students—to the ones who’d talk back to me, anyway—but I can’t claim that as a guest teacher I actually taught them. Most sub plans called for monitoring independent work time, which usually meant walking around and telling kids to quit watching YouTube or scrolling TikTok. I remember repeatedly asking one physically intimidating eighth grader, B, to stop playing Fortnite on his district-provided laptop. “No,” he’d practically shout. “No.”

Even in the gentle, quiet classes, the ones where no one had beef with their neighbors or threw giant balls of paper and tape, I was often shocked by how little work got done. Why did it take forty-five minutes to answer a few questions on a worksheet? I wondered if they would’ve tried harder if their actual teacher was in the room. Maybe. But also: maybe not.

“Students realized there weren’t any consequences for not doing their work during distance learning,” one teacher told me. “They could do nothing all year and still pass.” Now they were back in school, but the consequences didn’t seem any more real. It wasn’t only about missing schoolwork, either. A lot of kids came to class late or skipped entirely. Violations of the “off and away” cell phone policy were constant. Students threw fruit at lunch, punched their laptops when frustrated, and cursed without qualms. (M, an eighth grader who spent much of every school day wandering the halls, referred to teachers who asked her for a hall pass as “those motherfuckers.”) I assumed these kids saved their worst behaviors for subs, as we all did, back when we were their age—but when I sent my detailed reports to their teachers, I got responses like, “It sounds like you had a pretty standard day (for what it’s worth haha).” Every teacher I talked to—no matter the school—said this had been the hardest year of their career.

“You’re here on purpose?” That’s what my neighbor asked when we ran into each other on the field during yet another fire drill. As a TOSA—a teacher on special assignment—she’d been pulled from her regular duties to sub at several PPS middle schools. “I come out of it feeling demoralized and with a broken heart,” she later texted.

Depending on the day, I might come out of subbing feeling energized or traumatized, happy or wrecked. But I think what I felt most was stubborn. I didn’t want to give up on that school—or on those kids, even though they likely wouldn’t care if I did. After all, I was there only once or twice a week; it was their teachers who were down in the trenches, with or without real help from the parents and the administration and the district itself.

On the last Wednesday of the school year, I got assigned to cover eighth grade language arts. The eighth graders’ graduation ceremony was that night, so they were supposed to spend the first two periods practicing. Before that, though, came the sloppy, poignant parade known as the clap-out. As I walked “my” class down hallways lined with hundreds of clapping, cheering students and teachers, I cried again, and this time I knew why. I was proud of these kids, whether they’d mocked me or told me I was their favorite substitute. Whether they’d done their work or slept through class, they’d made it. I was moved, too, by the demonstration of school-wide support, the way I’m moved by any display of solidarity, be it a protest, a group performance, or a graduation procession.

I was also thinking about my daughter, who’d be graduating from eighth grade the very next day. Our lives were rolling onward, through these years of pandemic and megafires and political upheaval. My children—and all of these children—were growing up, and before we were ready for it they’d be gone from us.

The sixth and seventh graders kept clapping; I kept wiping my eyes. For a while I walked next to B, the kid who’d refused to stop playing Fortnite. He wasn’t super excited about graduating, he confessed, but he thought he was definitely ready for high school.

Emily Chenoweth is the author of the novel Hello, Goodbye, a coauthor of the Klawde: Evil Alien Warlord Cat middle grade series, and a frequent collaborator with James Patterson. She lives with her family in Southeast Portland.