Keiko's Legacy, 30 Years after Free Willy

Where were you in 1993? Belting along to “I Will Always Love You” or “All Apologies” on the radio? Waiting patiently for the next episode of Melrose Place or The X-Files, before bingeing was an option?

For Howard Garrett, who would cofound the Orca Network before the decade was out, most of 1993 was spent at sea, studying killer whales in the wild. It seemed kismet, then, when he found himself in a small town on his way to the San Juan Islands, and happened past the local theater. Two words on the marquee caught his eye: Free Willy. Something drew him inside.

“When the movie started, I almost couldn’t believe what I was seeing,” he says. “It was an amazing scene, showing these beautiful animals I’d just spent months working with, swimming together in their natural habitat.”

On the screen was Keiko, the killer whale costar of the film. This year marks the 30th anniversary of the release of Free Willy, and the 20th anniversary of Keiko’s death. In his honor, we look back at the legacy of the iconic orca, whose life drew admiration from a whole generation of ’90s kids, and ultimately changed the trajectory of marine wildlife conservation efforts for the better.

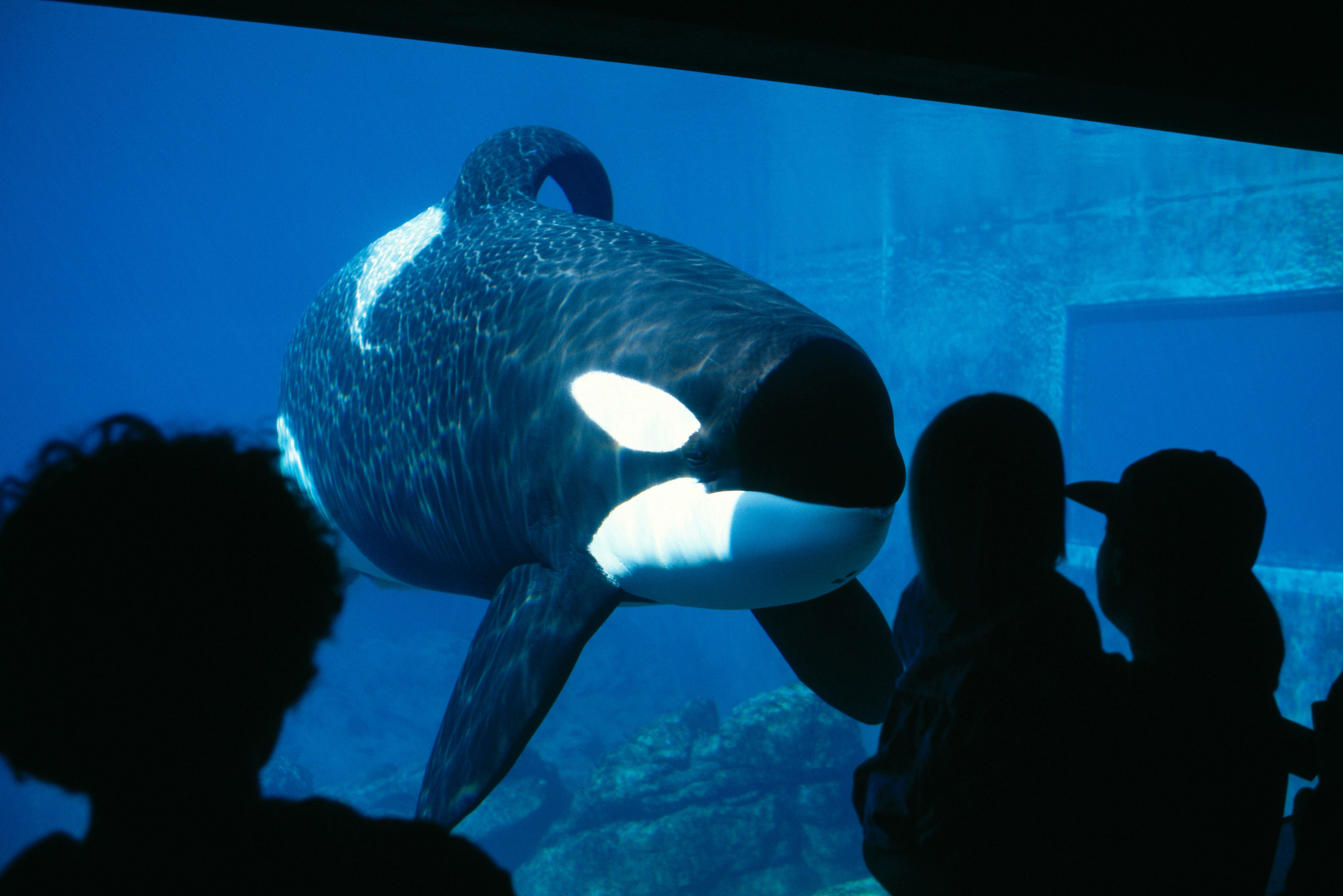

Keiko was a killer whale, born off the eastern coast of Iceland sometime in 1976. He was not, for the record, a literal whale; orcas are actually a type of dolphin, originally dubbed “whale killers” for their propensity to hunt whales in the wild. The species is unmistakable for its trademark glossy black-and-white-patterned bodies, and—with the second-heaviest brains in the sea—undeniable smarts.

“They’re very intelligent, and intensely social,” says Bob Pitman, who spent 20 years researching orcas with the National Marine Fisheries Service. “They’re a lot like humans in a lot of what they do—probably more any other cetacean. Plus: they’re big, and they’re beautiful.”

But these same defining traits—good looks and gray matter—are exactly what made the species such a hot commodity for (at the time, perfectly legal) capture, beginning in the early 1960s alongside the advent of SeaWorld-style aquariums throughout the world. Unfortunately for Keiko, he fell victim to the trade, and was taken from his family in 1979.

From there, Keiko traveled the world in captivity. He spent a few years at an Icelandic aquarium before moving to Canada’s Marineland, in Niagara Falls, Ontario, and eventually settling into the now-closed Reino Aventura amusement park in Mexico City in 1985. He spent his adolescent and teenage years there working on his performance chops and learning how to please a crowd, but it was anything but a glamorous life.

“Keiko had a rough go at it,” says Garrett. “His tank in Mexico City was way too shallow, originally built for [smaller] dolphins. He developed stomach ulcers, skin lesions, and was visibly underweight … all symptoms of severe stress.”

However, in 1993, Keiko caught his big break, when a group of Warner Bros. filmmakers discovered him at his longtime Reino Aventura residence. He had everything they were looking for—the talent, charm, that distinctive curved dorsal fin, even the background as a lonely amusement park orca in captivity—to cast him in their upcoming coming of age dramedy: Free Willy.

In case you weren’t a child in the ’90s, here’s all you need to know: Free Willy, filmed largely in Portland and along the Oregon coast, is the story of Jesse, a troubled preteen who develops a bond with Willy, the seemingly untrainable new orca at the local aquarium. Realizing that Willy is miserable, and that the money-eyed higher-ups in charge don’t have his best interests at heart, Jesse decides to set him free, back into the wild. In a grand finale—after the obligatory, tearful “goodbye” scene that’s still sure to well the eyes in 2023—Willy jumps the breakwater, swimming away and reuniting with his family, while Michael Jackson’s “Will You Be There” plays in the background. Willy has been freed. Roll credits.

It’s a sappy ’90s movie moment for the books, to be sure. But where Willy’s story ended, wrapped up in a neat little Hollywood bow, Keiko’s was about to get a whole lot more complicated.

The public response to the new cetacean celebrity was immediate and clear. The phone number listed at the end of the movie (1-800-4-WHALES), calling on viewers to “personally help save the whales of the world,” received hundreds of thousands of calls in the months following the film’s release, many from heart-warmed children. Fans couldn’t stand the thought that this now-beloved animal was back in his cruel, cramped quarters, when they’d just seen him break out of such confinements on the big screen. They wanted to “Free Willy”… but really, this time.

So, Warner Bros. teamed up with the International Marine Mammal Project (and billionaire cell phone industry mogul Craig McCaw, weirdly) to establish the Free Willy-Keiko Foundation. Priority no. 1 was to get Keiko out of Reino Aventura, and into somewhere with the resources to house him humanely and nurse him back to health. His destination? None other than Willy’s fictional home: the Oregon coast.

With more than $7 million in donations, the foundation was able to fund the building of a brand-new, two-million gallon tank for Keiko at the Oregon Coast Aquarium in Newport, complete with medical facilities and sanitized water pumped in from the bay. Keiko arrived via cargo plane in 1996.

“He was very affectionate and docile with his trainers,” recalls Jim Burke, who started working at the aquarium in 1997 and is now its director of animal care. “If there were people in the viewing window, he would come down and look directly at them. It was a pretty amazing experience.”

Keiko’s stay at the Oregon Coast Aquarium was a huge success. He gained around 2,000 pounds, his skin conditions and other health issues cleared up, and he was visited by more than 2 million starstruck fans. However, the Free Willy-Keiko Foundation had their sights set even higher. This was just phase one. With Keiko in good health and spirits, it was time to see Willy’s story through to the end, and free him back into wild, into the same waters he was taken from as a calf.

It was a controversial move from the moment of inception. A fully captive orca had never been re-released into the wild, after all, so no one was sure if it was even possible, let alone what all the necessary logistics would look like. Nevertheless, in 1998, after a brief two-year stay in Oregon, he was flown back to his home in the waters of Iceland, and the process of reintroduction was underway.

Once back in the ocean, Keiko remained under the care and supervision of humans (various nonprofits working alongside with Free Willy-Keiko Foundation, at this point). Though he learned to feed himself in the wild, assimilation into the local orca pods proved challenging; he would sometimes follow groups along, occasionally making his presence known, but generally keeping his distance.

If Keiko’s newfound life in the wild made one thing clear, it was his attachment to human company. Though free to travel the sea as he pleased, he made regular visits to his caretakers, in search of food and company. He even actively sought interaction with strangers, following fishing boats along the waters, letting onlookers touch and feed him.

Though Keiko remained seemingly healthy during most of his time back in the wild, his activity levels began to dwindle. He was sometimes seen floating motionless in one spot for hours on end, and gave up on any attempts to interact with local pods. Finally, in 2003, Keiko died of pneumonia in his free bay access pen on the coast of Skålvikfjorden at the age of 26.

Even today, the relative success of Keiko’s freedom attempt is the subject of much debate. One report deemed the project a clear failure, based on his inability to integrate with the local killer whale pods, concluding, “Keiko was indeed a poor candidate for release, due to the early age of his capture, long history of captivity … and strong bonds with humans.”

Bob Pitman agrees with this analysis.

“These are intensely social animals,” he says. “It would be like taking you or I out into the jungle of Africa and letting us ‘finally be free’ … To just release a single animal like that is bordering on cruel.”

Others, however, such as Howard Garrett, take a different view.

“By all accounts, he was happy and healthy back in the wild,” he claims, noting that Keiko took well to the natural water despite the socialization issues. “It is inherently wrong for these animals to be held in captivity, away from their natural environment. Any time they can be brought back to where they belong is a success.”

Regardless of how successful the Free Willy-Keiko Foundation’s efforts to free Keiko may have been, what’s undeniable is the impact that he had. Since his death, legislation has been passed throughout much of the world to effectively—or outright—prohibit the capture of the endangered species.

“In the United States, they don’t capture killer whales anymore,” says Pitman. “They don’t even allow them to breed in captivity; they’re completely phasing it out.”

Keiko may not be the sole harbinger of change for the world of marine mammal conservation efforts, but he certainly played a part.

“A lot of things changed after Keiko,” says the Oregon Coast Aquarium’s Jim Burke. “He opened up a lot of people’s eyes to animal welfare, and caring for things—whether that’s an animal that can’t be released back into the wild, or just observing and caring for our oceans, to give animals in the wild the best shot.”

“It’s Keiko’s legacy,” agrees Pitman. “He brought killer whales—and their plight—to the forefront. Anything that’s done to help killer whales probably grows out of exposure that people had to them in captivity.”