Who Killed Jordan Cove?

Bright orange paint on a mother tree. A throwaway letter about a property survey. An aggressive phone call: sell or else. A legal notice buried in a Coos Bay newspaper. For a handful of landowners, these were the early salvos in a fight that consumed their lives.

Their adversary was Jordan Cove, the largest energy project conceived in Oregon history.

For 17 years, the $10 billion gas plant and pipeline threatened to cut through tribal lands, ranches, timber holdings, and old-growth forests in the heart of Southern Oregon. Had Jordan Cove realized its quest to ship liquefied natural gas to Asia, it would’ve been the single largest polluter in the state, nullifying Oregon’s climate goals all on its own, releasing the greenhouse gas equivalent of 7.9 million passenger vehicles per year.

Yet, in December 2021, Jordan Cove died. Its multinational backers, once infiltrating communities from the California border to Coos Bay, evaporated. Seemingly overnight, an existential environmental threat disappeared.

But not its damage. For those who fought it, Jordan Cove lives on as an emotional scar. It gutted core beliefs about what it means to be a caretaker, a community, and an American. It nearly ripped this region in half. Some think it still might: resurrected in another form, by similarly distant power brokers.

How Jordan Cove got off the ground is the classic story of greed and opportunity. But, two years after its burial, Oregonians are still deciphering the improbable blueprint for its murder. What did it take to kill Jordan Cove? And more importantly, could we ever do it again?

“One day, I was walking through the property near a corner, and I happened to notice bright orange paint and a freshly blazed tree, with flaggings on all the trees around it,” says Francis Eatherington. “So obviously they’d have had to come on our property.”

Eatherington is on the board of the Oregon Women’s Land Trust (OWL), a storied lesbian feminist organization that emerged from the 1970s back-to-the-land movement. In 1976, the collective bought 147 acres of old-growth forest tucked deep into rural Douglas County near Canyonville. OWL Farm has only one usable road, nowhere near the proposed pipeline. Bobcats and elk use this patch of habitat, Eatherington says, and northern spotted owls nest close by.

“We love this property, and they wanted to take eight acres,” she says. “We said absolutely not. Not for a global warming fossil fuel project. And then they said, oh, for your eight acres we’ll give you ... two thousand dollars!”

The offer, which arrived by mail in 2013, felt ludicrous. The OWL Farm collective refused—as it had previous requests, dating back to 2006— to let Pacific Connector Gas Pipeline surveyors on the property.

Protesters rallied against Jordan Cove at the state capitol in 2019.

Initially, Eatherington knew Jordan Cove by many names, reflecting its fragmented story. The project was born in the middle of the second Bush administration—a few years before the North American fracking boom, and more than a decade before Standing Rock made pipeline fights a national conversation. Its namesake is a pocket of tidal backwater tucked into a long, narrow spit in Coos Bay, on Oregon’s south coast, long a hub for the timber and fish trades. More recently, it’s appealed to would-be shippers of fossil fuel.

Starting in the mid-2000s, companies like ExxonMobil, TransCanada (now TC Energy), and Kinder Morgan dreamed of a western route to move North America’s newly abundant methane gas (“natural gas” in industry branding)—through British Columbia, the Columbia River, or, perhaps, through the land known as Q’alya ta Kukwis shichdii me to the Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw.

Companies pursued all these routes, but the Jordan Cove Energy Project survived the longest, accumulating aliases. Pacific Connector was the 36-inch, 230-mile pipeline to be built through OWL Farm, while infrastructure behemoth Williams was the pipeline’s first public face. But Eatherington and others learned that the money behind the pipe and the proposed Jordan Cove export facility in Coos Bay was really a Canadian company called Fort Chicago. And Fort Chicago was hard to track. In 2011, it reemerged as a firm named Veresen. Later, it was swallowed by Pembina, a Calgary-based pipeline giant.

At first, the shifting faces of Jordan Cove made it hard for Eatherington to see much threat. OWL Farm kept saying no, and it seemed like enough; by 2012, the survey requests had dropped off. Even more promising, Fort Chicago/Veresen suddenly scrapped the plan it’d had since 2005 to import foreign gas through Coos Bay.

But Jordan Cove was simply changing form. By 2013, the project had become an export facility and pipeline that, Veresen assured federal and state permitting agencies, would ship “clean-burning” US natural gas to Asia.

That’s when Pacific Connector’s $2,292 offer arrived. Shortly thereafter, Jordan Cove hosted a series of “workshops” for landowners on its route. At one meeting, glossy 28-page brochures spelled out their choice: sell, or face the property seizure process known as eminent domain.

OWL Farm held strong. But its neighbors sold their rights-of-way, granting Jordan Cove’s reps the right to come and go at will along a 100-foot-wide corridor.

Then, on a March 2015 stroll, Eatherington saw the flagged trees. “I called the pipeline company and said, did you do that?’ And they said yes, we did. I was pissed.”

She turned to a lawyer, and within days, OWL Farm received a $10,000 check from Pacific Connector. It made the $2,292 offer feel even stingier.

By now Eatherington was all in. A lifelong environmental advocate with groups like Umpqua Watersheds, she knew that even a pipeline build-out can brutalize an ecosystem. In 2003, Coos County backed a 60-mile natural gas pipeline not far from Eatherington’s home near Roseburg. Roller-coasting over wildly steep terrain, the pipe was still under construction when winter rains flushed fish-killing excavating materials into streams.

Determined to keep OWL Farm safe, Eatherington reached out to other activists and angry landowners. Their motives varied. Some reeled from the idea of sinking $10 billion into a fossil fuel boondoggle. Others just didn’t want a 36-inch pipeline on their driveway. But they all agreed: Jordan Cove had to die.

The fossil fuel industry is notorious for messaging that makes it feel like an unstoppable force. For at least a century, it’s aimed to equate oil and gas with patriotism—essential to freedom and the American way.

Bill Gow points toward where a pipeline would have cut through his property.

Image: courtesy alex milan tracy

But there’s not much that feels American about eminent domain. And that really irks Bill Gow, who thought at least his fellow Republicans would fight for his property rights.

“We had a foreign company that wanted to use eminent domain against me, an American citizen,” says Gow, a beef rancher in the mountains east of Roseburg. “This wasn’t for the good of you or me. This was for the good of the company. And these companies own everybody.”

Local officials who dreamed of a “treasure trove” for local taxing districts. Silent politicians. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Even landowners who sold. For Gow, at first, everything felt stacked against him.

Like Eatherington, he knew little about the energy industry when he received his first survey request back in 2005. He didn’t like strangers, and these ones wanted to scope a massive pipeline? Hell no, he wrote, and got back to ranching.

But the letters kept coming. Then land agents started showing up at his ranch—older white men just like him, he noticed, intent on getting him to sign. That got his back up.

Gow started going to meetings; there, he met Eatherington and other landowners. Now he had allies—and, eventually, legal guidance from the Niskanen Center, a think tank in Washington, DC.

On the national stage, Gow’s predicament made for a powerful story. Jordan Cove would have sliced his ranch in half. As a miles-long, buried “bomb,” the pipeline’s no-go zone meant Gow wouldn’t be able to move his cows, transfer water, or even use the 100-foot-wide corridor for forage. Going along with it would’ve been preposterous. Yet fighting Jordan Cove still took over Gow’s life; his son even had to come help run the ranch.

On behalf of other landowners, Gow flew to DC to plead with congressional leaders and FERC representatives. He heard horror stories from other pipeline fights: a McMinnville farmer who spent a quarter million in court trying to end rampant trespassing, a Pennsylvania resident who couldn’t save her ancient maple trees cleared for a pipeline that was never built.

But by the first year of the Trump administration, the Jordan Cove opponents had scored a few victories. Oregon land use courts were pushing back, as were a few county agencies. Eventually, long-silent state officials chimed in. According to Pam Marsh, southern Jackson County’s state representative since 2016, activists like Gow had made Jordan Cove a story “no one could ignore.”

By then, Gow had invested more than a decade of his life in the fight. He was tired. The fatigue deepened as the new president began stacking FERC and other agencies with fans of his “energy dominance” platform.

In 2017, Trump’s new economic advisor Gary Cohn all but promised Pembina its pipeline, wrapped in the American flag. But Gow’s new friends had learned a secret: Jordan Cove’s product would almost certainly be 100 percent Canadian. It makes Marsh, the state rep, laugh to reflect on it. “I’ve always said their biggest mistake was going through Ron and Deb’s property.”

“The injustice of it all really bothered us,” says Deb Evans. “It wasn’t all about the environment. It was about how these big entities can come in and run over everybody.”

Evans and her partner, Ron Schaaf, have lived in rural Jackson County for the majority of their adult lives. Now mostly retired, they spent decades advocating for their daughter, born with Down syndrome. Activism was in their blood.

In 2005, the family bought a 157-acre timber holding sandwiched between national forests out in Klamath County, about 100 miles east of Gow’s ranch. On a scenic byway cradled within the protected viewshed of Mountain Lakes Wilderness, the property felt like a sound investment, both for leisure and financial security.

But a month after purchase, they were shocked to see a corridor of plastic flagging, 100 feet wide and a half-mile long, hanging from their new trees.

Evans and Schaaf hadn’t even gotten a letter; they had to figure out for themselves that their property was in the path of a massive gas project. Years went by, until a shock-and-awe call from a land agent in 2014: Jordan Cove was happening. Sell or else.

This was not their plan. Nor was the home doctorate in oilfield economics they gave themselves next, trying to convince agencies that Jordan Cove was a terrible idea.

“Pembina started putting out this whole advertising campaign with slick messaging—pictures of camping and dogs and fishing,” Evans says. “The big corporations really wanted to control the narrative. I think they underestimated what people are really made of.”

Schaaf and Evans investigated everything. By day they read through permit filings. By night, they’d fall asleep listening to Pembina’s quarterly investor calls and the speeches of Wyoming senator John Barrasso, who thought Jordan Cove would be “great news” for the shale gas plays in his state.

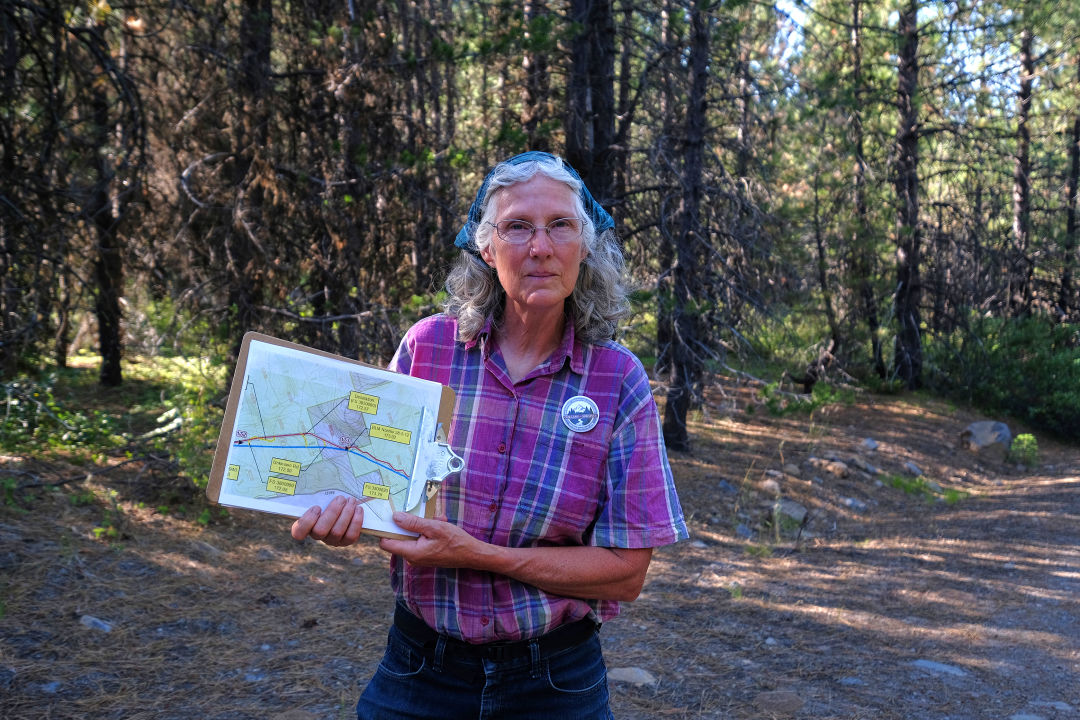

Deb Evans offers a technical view of the project’s route.

Image: courtesy alex milan tracy

Despite the enthusiasm of politicians like Cohn and Barrasso, Evans and Schaaf started to think that Pembina’s real friends were back in Calgary. They discovered that, in 2013, Canada’s national energy board had preapproved Pembina to export up to nine million tons of cheap Canadian gas annually across the US border, more than enough to satisfy all of Jordan Cove’s export needs. Soon after, the US Department of Energy greenlit all of that gas to flow through Washington and Oregon, citing free trade agreements.

In extensive filings, Evans and Schaaf shared what they’d found with FERC: It looked very doubtful Jordan Cove had ever planned to buy pricier American gas.

A FERC denial was nothing to count on; the agency only rejected two projects between 1999 and 2018. But back in Oregon, the project’s negative consequences were becoming clear.

If Jordan Cove happened, nearly 100 rights-of-way would be seized, including Gow’s ranch, OWL Farm, and protected wilderness near Evans and Schaaf’s holding. A flammable pipeline would roll over some of Oregon’s steepest, most wildfire-prone terrain, and under more than 400 rivers, wetlands, and coastal estuaries, risking fish-killing methane leaks and worse.

Oregon would be locked into a generational relationship with Big Oil and Gas, complicit in the future emissions of 36.8 million metric tons of greenhouse gases annually.

All for one company’s private profit?

Jody McCaffree didn’t consider herself an environmentalist, but she hated a con. In 2004, the lifelong Coos County resident saw a state filing about building a huge liquified natural gas facility on the bay’s fragile spit.

For McCaffree, whom the local newspaper once called a “relentless skeptic,” it felt off. She gave herself over to the work of untangling energy laws and regulatory processes, using her training as a courts accountant to wade through Jordan Cove’s dizzying data dumps—3,013 pages, in one case. She was the first on the scene, and, last year, the most recent to leave.

“She raised the alarm bell before anyone else really knew it was a thing,” says Hannah Sohl, executive director of the environmental nonprofit Rogue Climate. Sohl met McCaffree around 2013 as Rogue Climate coalesced from that year’s local National Climate Day of Action. By then, McCaffree had been rallying landowners like Gow for almost a decade.

“Jody really didn’t believe that the Jordan Cove project was following the rules,” Sohl says. “She dug into every detail.”

As McCaffree fact-checked Jordan Cove’s rosy job creation claims—finding that most would never leave Canada—Rogue Climate focused on the project’s climate costs. In 2018, it commissioned the DC nonprofit Oil Change International to look at how the project’s greenhouse gas emissions would square with Oregon’s goal of cutting 75 percent of state climate pollution by 2050. The group found that the project would be Oregon’s largest polluter. By midcentury, there’d be no way for Oregon to reach its target if Jordan Cove existed.

For those who’ve heard the industry line that natural gas is somehow climate-friendly—more “clean-burning” than coal, a “bridge fuel” till we get something better—the report is a useful reminder that it’s just another fossil fuel. And for climate activists like Sohl, any new fossil fuel infrastructure is a move in the wrong direction.

Gow, the rancher, is neutral on that topic. But he credits Rogue Climate for turning people out. By November 2019, thousands attended a Salem rally and sit-in at the offices of governor Kate Brown, including Klamath Tribes chair Don Gentry and longtime Oregon legislator Bill Bradbury, who died in April of this year. At one point, a bald eagle flew over the proceedings.

“People don’t realize the time we put into this, meeting after meeting,” Gow says. “If you ask me, it was death by a thousand cuts. And I’ll tell you what, Jody McCaffree is the reason we won.”

By then, McCaffree was starting to lose her personal fight with ovarian cancer. “It broke my heart the way that cancer ate her up,” says Gow. “And I’m not so sure the stress of this fight isn’t the reason why.” But the movement she’d seeded had grown into a force of nature. State agencies and elected officials, even senator Jeff Merkley, could no longer ignore it.

Pembina was losing the narrative, and the next wave of headlines didn’t help.

For years, in secret, the company had footed the bill for a dedicated security unit in the Coos County Sheriff’s Department. With Pembina funds, the “Combined Services Unit” bought a drone and an armored vehicle, and spent a lot of time on Facebook. In reports to a regional task force that included the FBI, deputies shared updates including their lack of progress uncovering a “criminal nexus.”

The surveillance made news in outlets from the Guardian to the Intercept. For many, it was the last straw. Jordan Cove was a property-seizing, privacy- invading, greedy, and unpatriotic climate nightmare. In Oregon, its support base was shakier than the sandbar from which it hoped to ship its product.

On March 19, 2020, FERC gave Jordan Cove an official rubber stamp—it was good to go. But Oregon had already said no. Months prior, the Oregon Department of Justice made a list of the ways Jordan Cove had failed to make its case to state agencies. Look closely and you’ll find traces of McCaffree’s work, and that of her many allies.

Pembina knew it was over. That March, a colleague of Sohl’s filmed a hasty move-out at Jordan Cove’s Coos Bay storefront. Still, the company waited until December 2021 to vacate its FERC authorization and officially give up the ghost.

Despite “diligent and persistent efforts,” Pembina informed FERC, “Applicants ... have decided not to move forward with the Project. Applicants remain concerned regarding their ability to obtain the necessary state permits in the immediate future in addition to other external obstacles.”

Less than a year later, Jody McCaffree died at the age of 62. She lived to see Oregon’s largest infrastructure project crumble under the impact of countless cardboard signs, court filings, sharpened pencils, and sharper minds.

Jordan Cove is dead, but the fossil fuel giants are undaunted. Pembina, Shell, and others are now pushing for an Asian gateway in British Columbia.

Meanwhile, the industry has learned from recent humiliations like Standing Rock—the protests against the Keystone XL pipeline—and Jordan Cove. Shiny new pipelines need lots of permits, creating more time for protests, politics, and bad publicity. But expansions of old pipelines only need buy-in from FERC.

That’s exactly the plan for the GTN Xpress, a 62-year-old pipeline that runs from northern Idaho through Washington and down the Eastern Cascades to the Oregon-California border. It’s the same pipeline that Jordan Cove would have used to get its gas from Canada.

GTN’s backer is TC Energy, the Canadian company behind the Keystone XL. If FERC approves the GTN Xpress expansion, three million metric tons per year is a conservative estimate of how much new pollution GTN would create.

Meanwhile, Pembina still owns the rights-of-way sold by 172 landowners along Jordan Cove’s route: sunk costs it can recoup only through another energy project.

If there’s one takeaway from Jordan Cove, it’s that it almost happened. Killing it took 17 years, and thousands of cuts. It will take at least that much next time to keep it in the ground.

Editor's note: A previous version of this story misstated the county where Deb Evans and Ron Schaaf have lived for the majority of their adult lives. It is Jackson County, not Douglas County. Portland Monthly regrets the error.