Two Photography Exhibitions Offer Rare Photo Record of Life Under Nazi Rule

Deportation, people walking looking at camera, small boy in center escorted by Ghetto police, 1942-1944, gelatin silver print from a half tone negative. ART GALLERY OF ONTARIO

Gift from Archive of Modern Conflict, 2007 2007/2417. © 2018 Art Gallery of Ontario.

This fall the Portland Art Museum (PAM) and the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education (OJMCHE) present two exhibitions that offer an extraordinarily rare glimpse of life inside the Lodz Ghetto through the lens of Polish Jewish photojournalist Henryk Ross (1910–1991)—Memory Unearthed: The Lodz Ghetto Photographs of Henryk Ross at the Portland Art Museum and The Last Journey of the Jews of Lodz at the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education.

Ross, confined to the German-controlled ghetto in 1940, was charged with making official propaganda photographs for the Nazis. He also secretly photographed community-affirming as well as devastating realities of life during the Holocaust. With the hope of preserving a historical record, Ross buried more than 6,000 of his negatives in 1944. Nearly 250 surviving images are included in the exhibitions.

Judy Margles, the director of OJMCHE and Julia Dolan, curator of photography at PAM reflect on the exhibitions and their importance at this moment in time.

Children being deported to the Chelmno nad Nerem (renamed Kulmhof) death camp, 1942 half-tone positive on polyester film base with paint on verso. ART GALLERY OF ONTARIO

Gift from Archive of Modern Conflict, 2007 2007/2547.4. © 2018 Art Gallery of Ontario.

How do you see art as playing a role in remembrance, tolerance, and education?

J.M. Art brings communities together. We know from research that that exposure to stories of other cultural experiences through art increases empathy and the ability to see other viewpoints. We see this time and time again at OJMCHE, especially with visitors who are interacting with our exhibitions about discrimination and resistance and the Holocaust. Art makes certain that what might seem unthinkable and remote in our collective memory remains as an indelible mark on our conscience. Henryk Ross is an ideal example—in his expressive photographs that depict the chain of events in the ghetto, he evokes an almost tangible sense of reality. Within this grim reality, Ross also manages to convey the resilience of the human spirit and hope.

J.D. Photography can give us a direct connection to someone’s lived experience. In this case, we can see through Ross’s camera and see much of what he saw, which links us to his experience while confined to the Lodz Ghetto. His photographs depict the people who were confined with him, as well as those who were forced to do manual labor, and starve, and be deported to death camps solely because of their religion and familial backgrounds. We witness this horrific reality through Ross’s photographs. These images remind us of the crimes against humanity that can occur when hatred goes unchecked.

Industry: workers in the textile workshop sewing, 1940-1944 gelatin silver print. ART GALLERY OF ONTARIO Gift from Archive of Modern Conflict, 2007 2007/2134. © 2018 Art Gallery of Ontario

How do OJMCHE and PAM respond to, and serve our local community in times like this?

J.M. OJMCHE bears the growing immediacy of our mission and each day brings us another sobering reminder of the relevance of our work, a feeling that grows more urgent each day. We strive to nurture a safe space in which visitors can find the relief offered by the intimacy of human experience. Our gallery docents are ready to talk with visitors who seek conversation. In our public programs we address urgent issues as they arise. Forging partnerships that encourage inclusion and foster understanding are a top priority.

J.D. Many people find comfort in art museums during difficult times. I like to encourage folks to also consider challenging artwork within our galleries. Museums are places that allow us to slow down, look carefully, and think critically. We are bombarded by photographic images all day, every day, and must consume them rapidly. Museums invite us to take more time, to think and feel deeply, and can provide a supportive space to consider tough subjects.

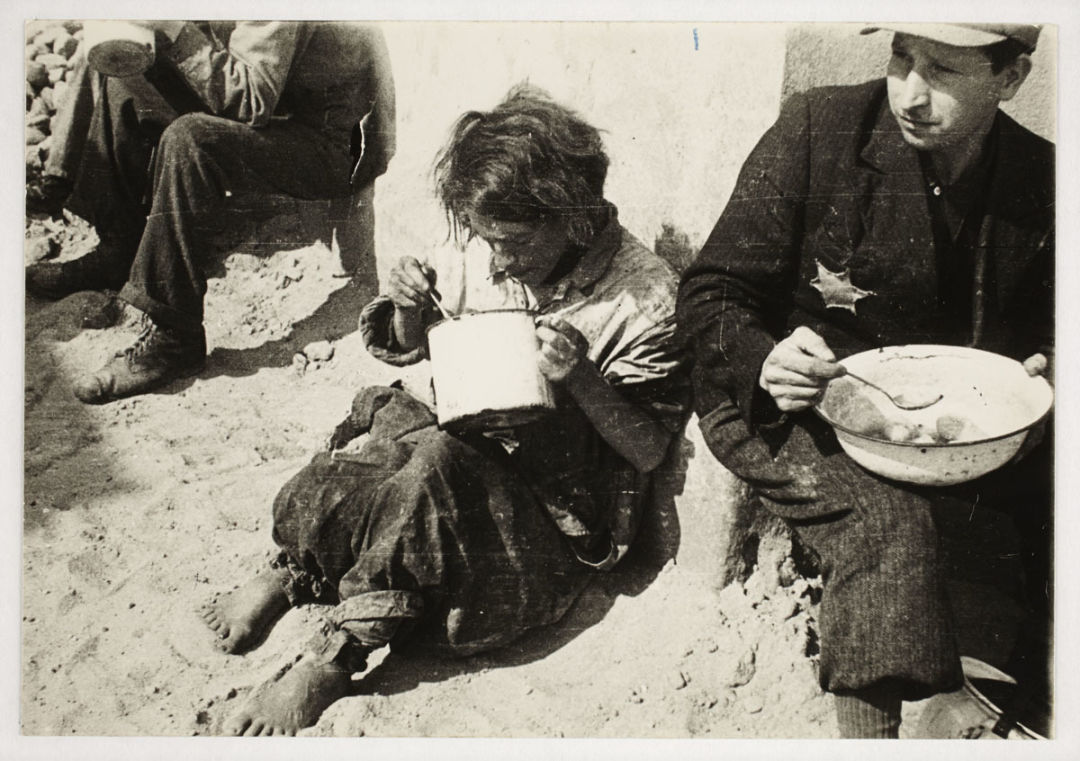

Man and woman eating from a pot and a pail on a street corner, 1940-1944 gelatin silver print. ART GALLERY OF ONTARIO Gift from Archive of Modern Conflict, 2007 2007/2167. © 2018 Art Gallery of Ontario.

What impact does having these exhibitions on view at the same time have?

J.M. Memory Unearthed and The Last Journey of the Jews of Lodz serve as bookends to one another. While both show photographs taken by Henryk Ross while he was imprisoned in the ghetto, Memory Unearthed is perhaps the more personal of the exhibitions, displaying fully, the stark breadth of ghetto life and the longing for normality that incarcerated Jews tried to create. The Last Journey of the Jews of Lodz focuses on Ross as witness to the events and conditions of suffering that led to the last journey to Auschwitz—the liquidation of the ghetto—in 1944. Similar to the survivor testimonies in our oral history collection, Ross’s photographs transcend time and place. Using his camera as a tool of resistance, he emboldens the viewer to envision the complexity of human experience in the ghetto.

J.D. Community institutions like OJMCHE should not have to bear the weight of the history of the Holocaust on their own. We can join forces to share that burden, and reach wider and diverse audiences together.

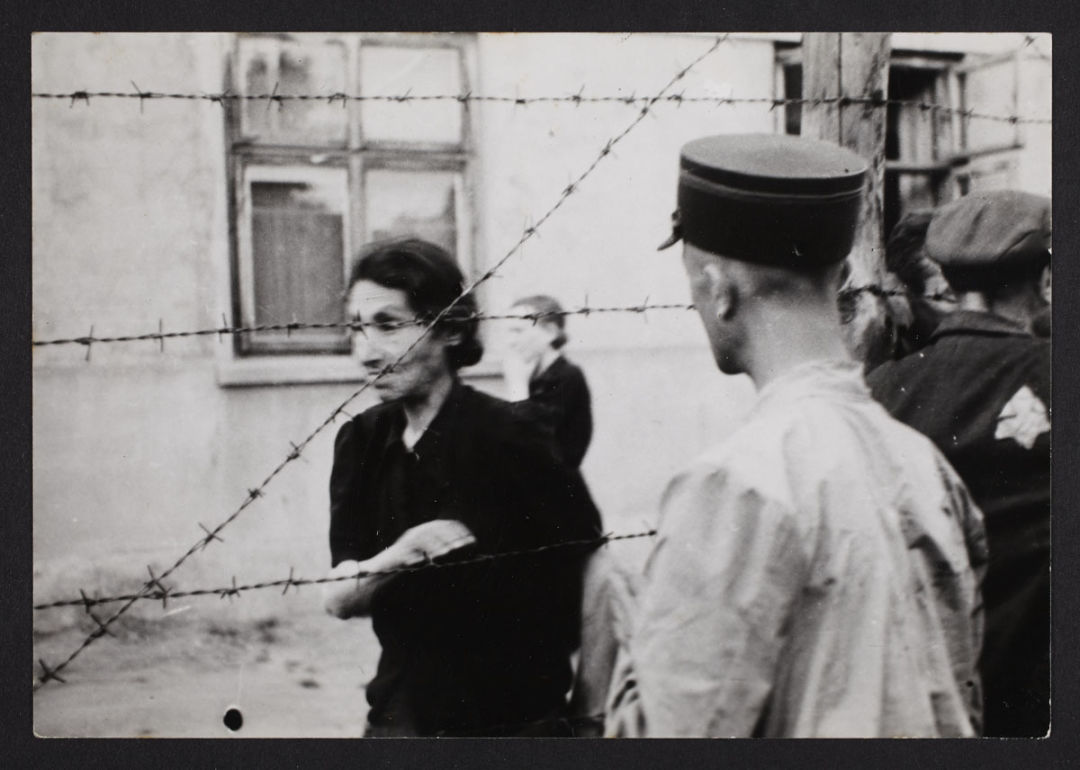

Ghetto police with woman behind barbed wire, 1940-1944 gelatin silver print. ART GALLERY OF ONTARIO Gift from Archive of Modern Conflict, 2007 2007/2185. © 2018 Art Gallery of Ontario.

Read the full version of this interview on the Portland Art Museum website.