The Yasui Family: An American Story

“The Yasui family story is an American story.”

This is the text that greets visitors as they walk into the Oregon Historical Society’s newest exhibition, which examines painfully relevant questions about citizenship, immigration, and belonging through the lens of one Oregon family.

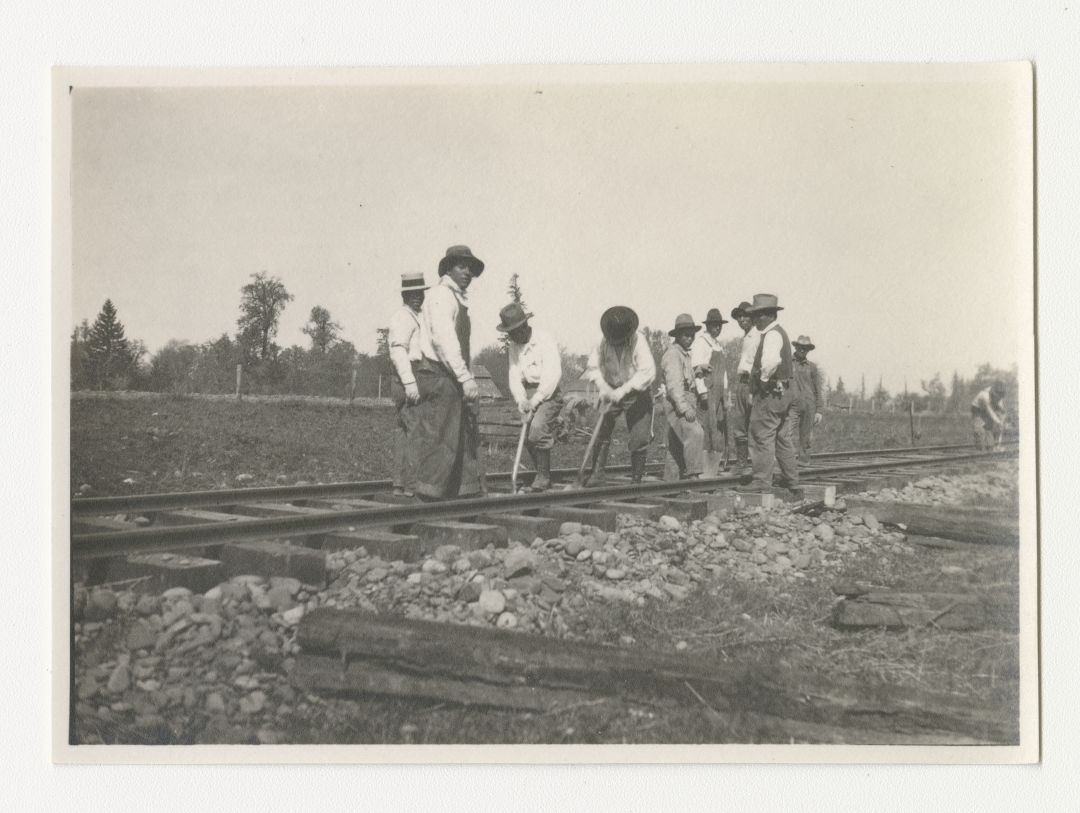

Members of the Yasui family were among the millions of immigrants who came to the United States seeking new opportunities during the late 1800s and early 1900s. The exhibition follows in particular the story of Masuo Yasui, who immigrated to the U.S. in 1903 at the age of 16. He joined his brothers and his father working for the Oregon Short Line, where he stayed for two years before moving to Portland. While many Issei (first-generation Japanese immigrants) saved money so they could create a better life if they returned to Japan, Masuo saw few prospects in returning and instead chose to pursue his own ambitions in the United States.

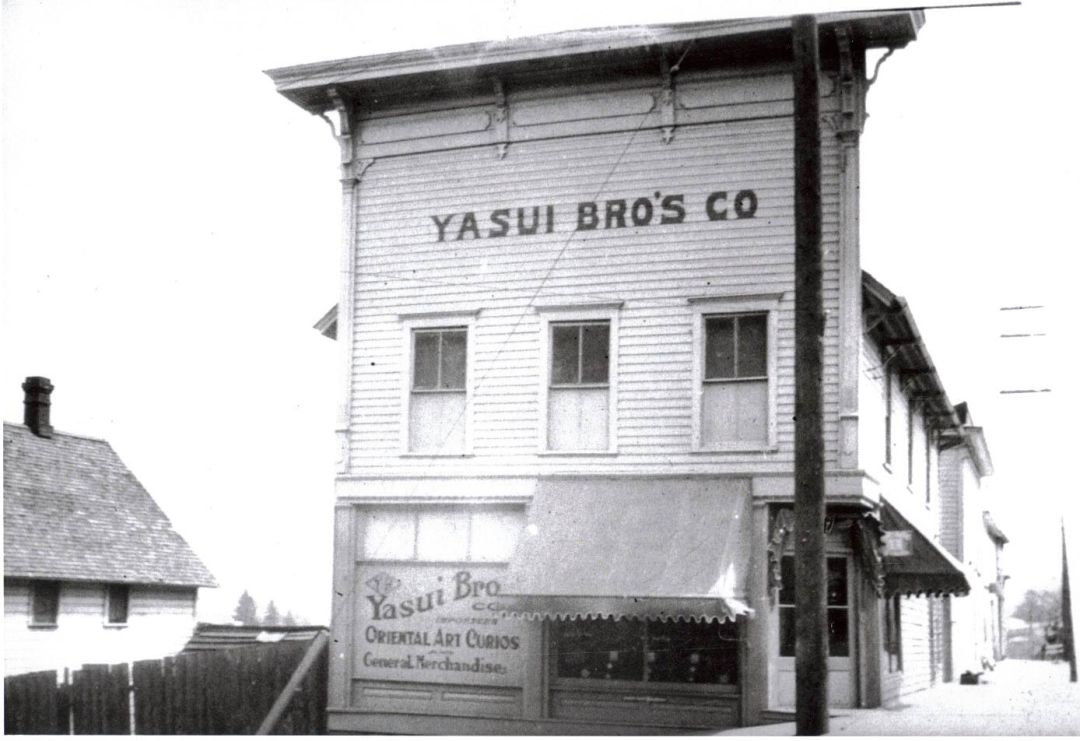

In 1908, Masuo moved to Hood River, a city that had an established community of Japanese immigrants who came to the valley to work in agriculture and logging. Along with his brother Renichi Fujimoto, Masuo opened the Yasui Bros. Co. store, which carried a mixture of Japanese and Western goods — examples of which are on display in the exhibition inside an immersive storefront. While they were not the first store in Hood River to carry Japanese goods, they were the most successful.

Racism and oppression were common, yet Nikkei (Japanese immigrants and their descendants) like the Yasui family persisted in establishing roots in Oregon, starting families and businesses, and shaping the social and economic fabric of the communities where they lived.

However, life for people of Japanese descent drastically changed when the Empire of Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, flaming existing anti-Japanese propaganda and inciting further violence and exclusion.

The day after the Pearl Harbor attack, the U.S. Treasury Department shut down the Yasui Bros. Co. store. Renichi was briefly allowed to reopen the store for a month-long liquidation sale before it was closed completely on April 18, 1942, after 34 years in operation; it never reopened.

Under the authority of the Alien Enemies Act, Federal Bureau of Investigation and U.S. Army agents detained pre-selected “enemy aliens,” mainly Issei community leaders such as Masuo Yasui. Although not officially charged with a crime, Masuo was arrested five days after the Pearl Harbor attack.

Several weeks later, on February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the U.S. government to forcibly remove over 110,000 Nikkei — including U.S. citizens — from their homes and send them to concentration camps, often in remote areas. Life in the camps was physically, mentally, and emotionally harsh, and Nikkei remained there for the majority of World War II. After the war, many members of the Yasui family returned to Oregon, although some incarcerees chose not to return home due to persistent racism in their communities.

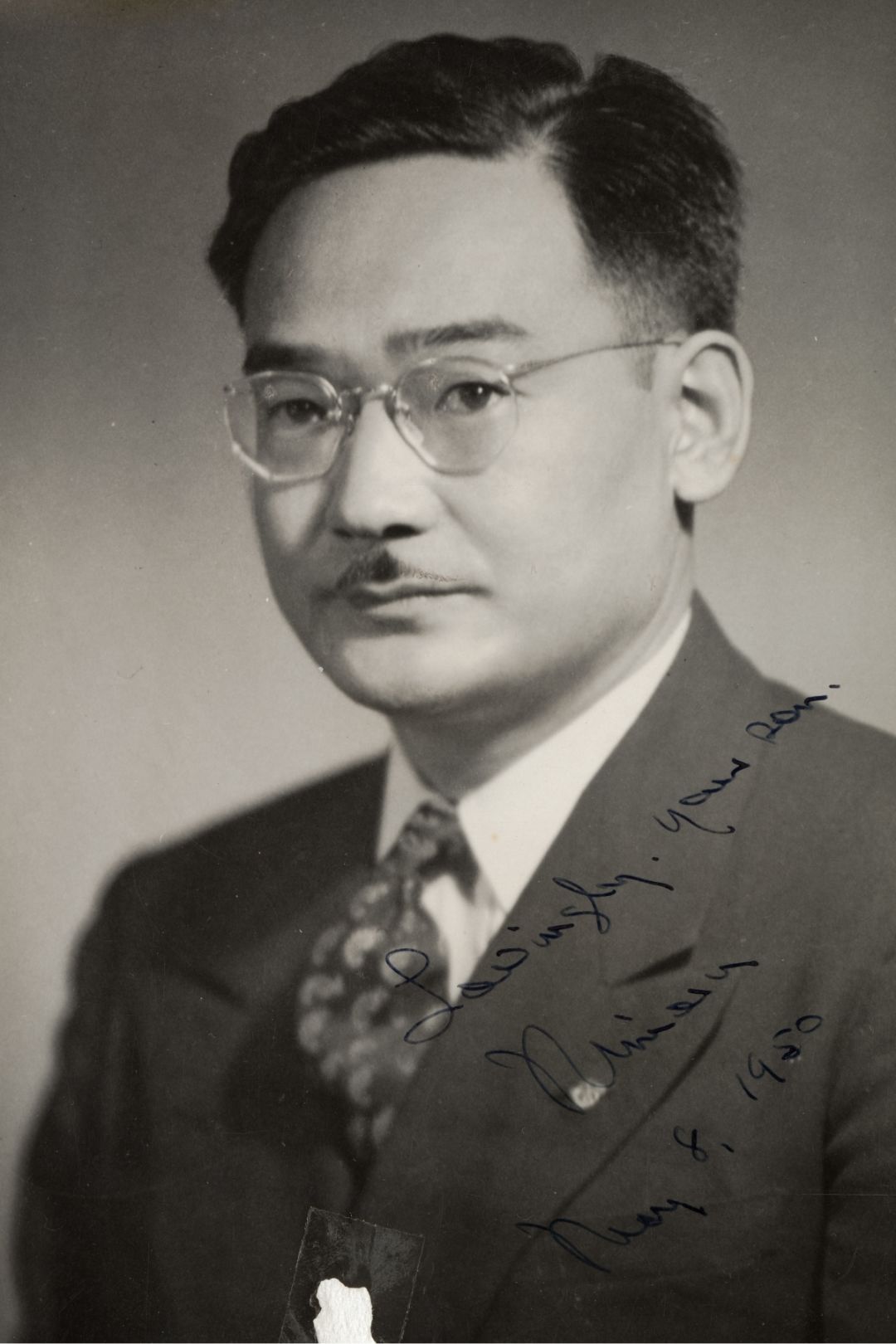

In the decades after incarceration, Japanese Americans fought for restoration of their civil rights, monetary compensation, and most importantly, an apology from the U.S. government. Thanks to the tireless work of activists, including members of the Yasui family like Masuo’s son, Minoru Yasui, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was passed. It included a formal apology and $20,000 in monetary compensation to every surviving U.S. citizen or legal resident of Japanese ancestry incarcerated during World War II — though by then, many former incarcerees had already died. For his attempts to challenge the constitutionality of wartime curfew, Minoru was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015, the only Oregonian to receive the award.

The Yasui family’s history is both unique and similar to the experiences of other immigrants to the United States; it reflects the complexity of the American story. And, like many families, generations of the Yasui family have preserved their traditions, history, and ongoing legacy. It is through their photographs and personal correspondence, business records, and belongings — many now in the care of the Oregon Historical Society — as well as firsthand accounts that historians have insights into the lives of Japanese immigrants and their families in Oregon during the twentieth century.

The Yasui Family: An American Story is on view at the Oregon Historical Society from June 13, 2025, through September 6, 2026. The Oregon Historical Society’s museum is open daily in downtown Portland, from 10am to 5pm Monday through Saturday and 12pm to 5pm on Sunday. Admission is free every day for youth 17 and under, OHS members, and residents of Multnomah County.