Q&A with Rand Miller, Designer of Digital Worlds

Rand Miller, Cyan

When Rand Miller and his brother Robyn Miller released Myst in 1993, video gamers didn’t immediately know what to make of it.

In a market filled with pixelated plumbers, hedgehogs and gorillas, the 3D-rendered universe of Myst was not just stunningly beautiful (at the time), the gameplay was revolutionary. There were no enemies, no bosses, and no levels. You couldn’t jump or shoot fireballs. There wasn’t even any discernible objective or narrative. All you could do was walk around a deserted island, examining old ruins and buildings.

Only slowly, through hours of exploration and experimentation, did a story begin to emerge: seemingly inert objects became puzzles and clues, buildings became portals to distant worlds, and each discovery slowly drew back the curtain on the island’s deep, dark history.

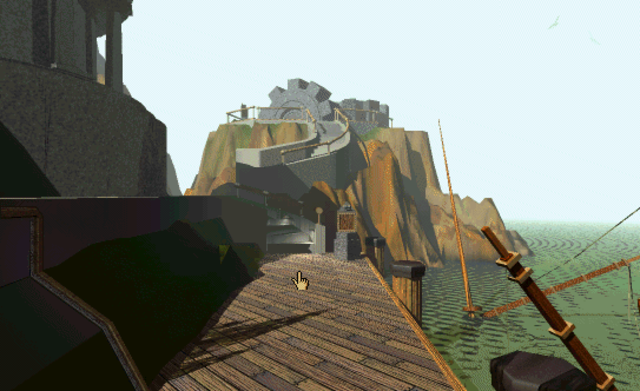

The starting point of Myst (1993)

The game was an instant classic—the definitive exploration and adventure title for the next decade. It spawned an entire franchise, including an excellent sequel, Riven, and a series of books.

Last month, the Miller brother’s company, Cyan, completed a successful Kickstarter campaign to fund Obduction, a big budget adventure game—a genre that has fallen into severe neglect since their original efforts. The campaign was more than successful, raising $1.3 million (about $300,000 more than their target). While the project is still in the initial design phase, concept artwork (some of which is shown below) shows the hallmarks of their earlier work: rich landscapes and architecture, vacillating between organic and industrial, alien and familiar.

We talked to Rand Miller about game design, the gaming architecture, and what makes a world interesting.

How long have you been working on Obduction before the Kickstarter campaign?

The original concept is 10 years old. It has been being developed in different phases for that amount of time. But the Kickstarter campaign was great. It was nice to be in touch with people that know our games. We are all the way out here in Spokane. I always live in a world where I don’t think many people know about us. We are getting so many positive reinforcements and great comments and gotten so much energy.

For Riven, your designers went out into the world and took a ton of interesting photos to use as textures in your digital worlds?

Yeah! That’s a true story. A few of the art guys took a trip to New Mexico. That was a great place to get those outdoor, worn, cultural, and archaeological based textures. And we still have a ton in our texture library that we never used for Riven.

But we also need to remain conscious of our budget, because unlike Riven we don’t have such a lavish budget where we can pay our art guys to go to New Mexico. So this time around we will be staying closer to home.

In terms of the architecture of the world, how do you go about designing it?

Image: Cyan

It is interesting that you bring up ‘architecture of the world’ because that is how it is. We start with the top-down view of the place and we start filling in.

In actuality, we don’t really need to fill in the details of the buildings, but it helps fuel the story. We draw a little bit of our space and we put a building in. That fills in the story a bit which can lead to the next building. It builds like a puzzle.

It is a recursive process where one aspect of the architecture feeds into the game play which feeds into the story line which feeds back into the architecture which feeds back into the game play which feeds back into the story line. It just starts to grow.

Do you have any designers with backgrounds in architecture?

Not right now, but we’ve used those before. For one of our online Myst projects, we worked with Mark Engberg, an architect out of the Portland area. He was amazing. We were designing an entire history of this culture and the phases of architecture they went through.

An architect usually has certain constraints in mind. He usually has certain rules and regulations. In the virtual world, it is more of a creative process with not many limits. The only limits in our virtual world is that we want it to seem familiar so that it has an air of reality, so that it rings true. But we also want it to be unique enough so that you wouldn’t just run across it in your everyday life either.

How does the architecture of the game world influence the story?

Image: Cyan

I’ll give you an example from Myst. When we were sitting down designing it, we knew we wanted an island, so it was natural to start with the dock. I was sitting down with my brother Robin and he just drew a giant hill on the side of the dock and then he put a big gear on the top of this thing. That gear didn’t have meaning at first. It was just an artistic element and we didn’t know if it was going to stay or not. But it became the seed of an idea that we realized would be interesting to see this gear related to another part of the island. So then we featured mechanical items featured from another age with gears strung about. Just having that seed of an idea filtered through a lot less of the design work.

Both Myst and Riven are, for the most part, unpopulated. Are you going a similar route with Obduction?

Yeah. The way we interacted with characters in Myst and Riven was fairly deliberate. It’s interesting because we throw that phrase ‘character interaction’ out pretty easily. But the reality is it is not easy to interact with a character in a virtual world. They usually break the spell. They come across as flat and you can’t really talk with them. The only questions you are really supposed to ask are those that are pre-planned. It’s not very satisfying. I can’t ask, ‘Hey, how are the kids and wife?’

What we have to do is build an illusion that helps you suspend your disbelief. There's no dialogue tree. The audience, the player is mute: it listens, gathers information, and communicates with the world only by doing or not doing what other characters tell it.

When Myst and Riven came out they were mind-blowingly photo realistic. Are you hoping to push that boundary again?

There has been an amazing number of games that have come out lately where sections of them are absolutely beautiful. You can see worlds becoming much more real and much more interesting. We look at that and just drool. But it’s used mostly for first person shooters. You’re in a panic because there’s a zombie or monster that is trying to kill you. You can’t even enjoy the world. The way we describe it is, we want to use the latest and greatest technologies to build a place that you want to live in, not die in.

Your earlier games are all set in the same universe. What made you want to move away with that and start a whole new story with Obduction?

Image: Cyan

It’s really about motivation. On some level doing these adventure games and exploration games is a heck of a lot of work. We don’t have our gameplay laid out in front of us. If we are doing a shooter, it's pretty straightforward: you have to concentrate on creating a bad guy and weapons, and build some levels that the bad guys keep you from getting through.

But with the adventure games we get to build every element and we get to re-design the gameplay. You can’t reuse puzzles and redo stories. It all has to be fresh and clean. I think that’s why there are not a lot of adventure and exploration games. They’re expensive and they’re a lot of work.

So with that in mind, we were going to revisit and reimagine Myst. But when we sat down to think about it, it didn’t make us excited. When we started with a blank sheet of paper and thought about Obduction and how that idea had never been done we got invigorated.

Do you think you can capture lightning in a bottle a third time?

There is a deep human desire of discovering what’s around the next corner. You go someplace new because you aren’t sure what you are going to see. Our goal is to just play off that human emotion and to get that balance of friction and reward. You have to solve the puzzle, not just find the bad guy. And we also have to make sure it isn’t too hard so that way you feel rewarded at the end.

Say, you’re on a road trip through the Western US, you can go a long time before seeing something interesting. There isn’t a national park every two minutes. There’s a battle between the reward and having to wait for a discovery. On the other end of the scale is Disneyworld, where they jam as much pleasure as they can into every space possible. We are trying to decide where we stand between those two worlds. We want to pack it in but we also want a sense of anticipation and suspense.

We are not geniuses, but I think Myst was successful because it was the right combination of the puzzles and rewards. In the end, we want people to remember these places as real places and if we have done that then we have done our jobs.