Why Portland Desperately Needs More Urban Density

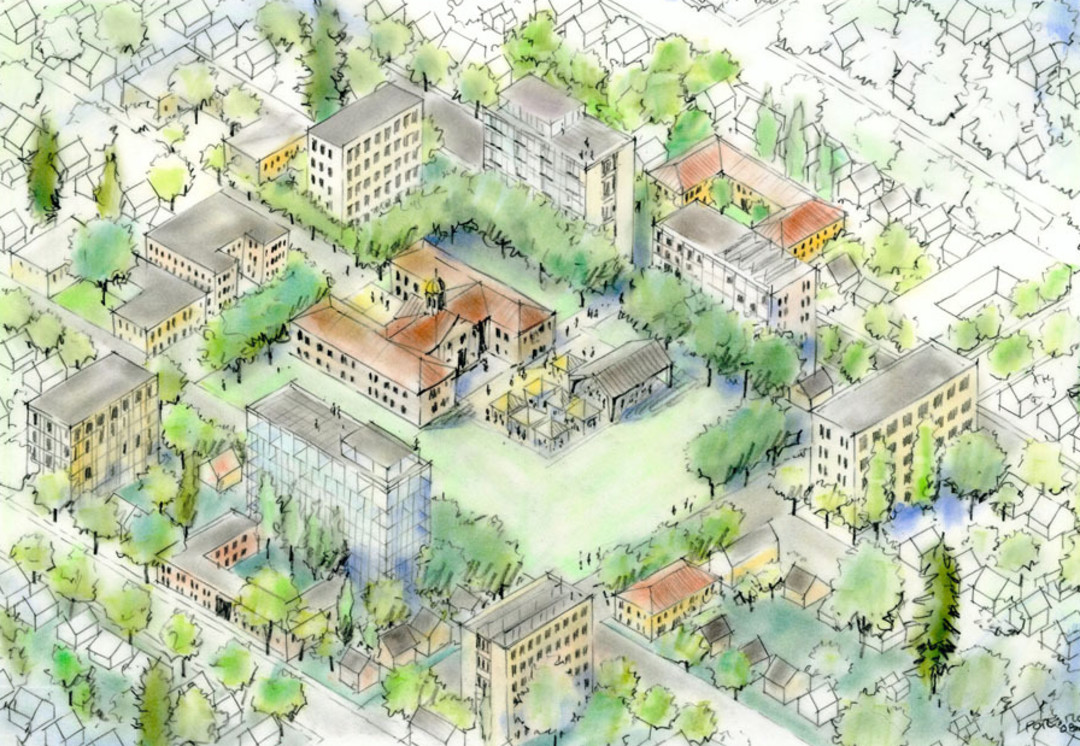

This conceptual drawing illustrates Rick Potestio's vision of a Portland built around parks and schools.

Editor's note: In Portland Monthly's April feature on the city's real estate boom, we reported on local architect Rick Potestio's "modest proposal" to remake Portland urban planning. Potestio agreed to provide more detail on an idea he says can help the city grow without losing its soul.

Quick: is Portland a dense, urban city?

Most casual observers would probably say, well, of course. Our city planners have made density a mantra for 40 years. And much of the angst—as well as the excitement—about the construction now remaking the central city focuses on apartment and condo projects, like the Lloyd District’s huge Hassalo on Eighth or the cluster of new midrise buildings on Southeast Division.

But here’s the surprising truth: Portland ranks near the bottom of West Coast cities for the very qualities it champions: dense, mixed-use urban form.

THE NUMBERS DON’T LIE

Consider one measure: Density of persons per square mile within major West Coast cities (as compiled by CityData).

- San Francisco: 17,935

- Berkeley: 11,164

- Los Angeles: 8,281

- Seattle: 7,779

- Oakland: 7,247

- San Jose: 5,710

- Sacramento: 4,937

- Portland: 4,537

- San Diego: 4,180

At the regional scale, according to Demographia.com, the Portland metro area ranks 19th in density nationally. San Jose, Fresno, Las Vegas, Phoenix, Denver, Salt Lake City, Sacramento—all denser.

Even more surprisingly, central Portland isn’t even as dense as many of its own suburbs. Check out this CityData info:

- Aloha: 6,702 persons per square mile

- Cornelius: 6,421

- Happy Valley: 6,047

- Beaverton: 5,731

- Gresham: 4,938

- Tigard: 4,644

- Sherwood: 4,637

- Portland: 4,537

- Hillsboro: 4,514

How did this befall the city that fancies itself a beacon of urban living? Politics, regulations, and market forces.

Senate Bill 100, which established our urban growth boundary, requires a 20-year supply of developable land, with regular updates. So as the region gains weight (population), that belt expands, a few notches at a time.

An adjustable urban growth belt allows our leaders to avoid unpopular proposals. Residents can reject planners’ proposals for infill, taller buildings, or changes to zoning. Developers, in turn, will always seek new land to meet the demand.

If we keep growing as we are now, this weird, flip-flopped condition—suburbs more dense than the city center—is going to continue and magnify.

Projections state the region will add as many as 750,000 people by mid century. Twenty percent of the expected population will go into the city of Portland, where the average density is between 6-10 housing units per acre. The remaining 80 percent will push into the ‘burbs, in housing tracts of about 18-30 units per acre.

This is sprawl on steroids.

Truly sustainable cities concentrate population at their heart, where mixed land use and density give residents economical and efficient transportation, services, and amenities. Our unsustainable future will locate the bulk of our population in a suburban, auto-based context.

Meanwhile, in the city, current plans for high-density development imitate either Seattle’s apartment blocks (Division) or Vancouver, BC’s glass-tower “centers” (South Waterfront.) Thus the city’s vintage neighborhoods may remain largely free of development, except for a few skinny houses, corner duplexes, and ADU’s. And this sounds fine, until one realizes that the situation we’re replicating is actually San Francisco. In San Francisco, zoning severely restricts new development in historic neighborhoods. Demand far exceeds supply, and prices are skyrocketing—the median home price now hovers around $1 million.

Portland’s currently crazed real-estate market—with cash offers well over asking price common for central-city homes, and rentals hard and expensive to come by—strongly suggests we’re headed in that same direction.

IS THERE A SOLUTION?

The very notion of higher densities in established neighborhoods tends to trigger classic NIMBYism. Many Portlanders hate the backyard ADUs and skinny houses now proliferating in our historic central neighborhoods. And I agree that both are very inefficient housing types that waste valuable land by converting it into useless 5-foot wide strips to meet setback regulations. But opposition to specific housing forms doesn’t stop the fact that population growth is coming.

So what is the answer? I propose it is in our backyards, so to speak: the building pattern that occurred incrementally as Portland’s neighborhoods evolved between 1900 and 1929.

Many of what we now think of as central-city neighborhoods were originally “suburbs,” intended for the well-to-do. But as the city grew, these neighborhoods filled with working-class families, and builders met the need with diverse housing. So in neighborhoods such as Irvington, a mansion sits adjacent to a bungalow on a block that may also have four-plexes, courtyard apartments, and more.

The Portland Heights neighborhood is an example. At the intersection of SW Spring and Vista, one finds a school, fire station, restaurant, offices and shops, and a few steps away, a church. These blocks contain a variety of apartments, townhomes, mini-houses, and mansions, whose servants’ quarters are today’s equivalent of ADU’s.

Portland’s densest neighborhood is the King’s Hill section of Goose Hollow. At its heart, the density is 70 to 100+ units per acre. Yet the neighborhood hardly feels like the Pearl District or South Waterfront. Rather, tree-lined streets define blocks filled with a dynamic mix of historic homes, townhomes, courtyard apartments, and condo towers. Mixed in are professional offices, a gas station, auto dealerships, a tavern, three social clubs, and a soccer stadium. Open spaces are well-tended public and private gardens. A 24-story building stands nearly as tall as the sequoias in the courtyard of the two-story apartment complex next door.

How does a neighborhood with so much diversity in buildings and activities maintain an ambiance that attracts tourists to walk its streets? It is precisely because of the variety that it all fits together so well.

THE VISION

I propose that Portland adopt the diversity and variety of King’s Hill as a model for all its neighborhoods.

I envision a “garden city” in which each neighborhood has at its heart a “commons” comprised of the neighborhood’s school and park. The surrounding streets will transform into tree-lined pedestrian esplanades. Cafes, shops for the needs of everyday life, and a tavern or two, set in the ground floors of slender apartment towers nearly as high as the trees, frame those esplanades. Neighbors gather, stroll, shop, linger, and eventually filter back down quiet streets to all manner of housing. A few blocks away in each cardinal direction is a busy boulevard with transit and bike lanes connecting to the rest of the city.

If central Portland achieved an average density of 18-25 units per acre, (the same as the suburbs we’re planning to build now), the city would easily accommodate all the region’s expected new residents. And it would do so without sacrificing its quality of life or the characteristics held so dear.

Neighborhoods will be more affordable, diverse, equitable, and sustainable with the addition of a variety of housing types—most importantly, suited for the families that have largely abandoned San Francisco and Seattle.

Farms, forests, orchards and vineyards will remain as they are, as the UGB will not be expanded.

Schools, streets and sidewalks, infrastructure, and parks will be restored with the proceeds from new taxes and development fees.

HOW IT COULD HAPPEN

The bullet points:

- Organize each neighborhood around a “commons” comprised of its school/playground and park

- Plan for a variety of housing types and small institutional and service uses, mixed together throughout the neighborhood

- Use Portland’s historic housing types as models: twin houses, town houses, courtyard apartments, etc., of up to 4 stories

- Repurpose key streets as esplanades around public parks and open space

- Locate the tallest buildings around opens spaces, wide streets and areas with tall trees

- Each neighborhood association would be entrusted to develop a plan that would guide new development. Based on its area, location, and population density, each neighborhood would be responsible for accommodating a proportionate share of new residents.

The idea of changing our complicated and politically ingrained planning process seems daunting. But the alternatives—sprawl, gentrification, and a loss of Portland’s treasured character—are far more ominous.