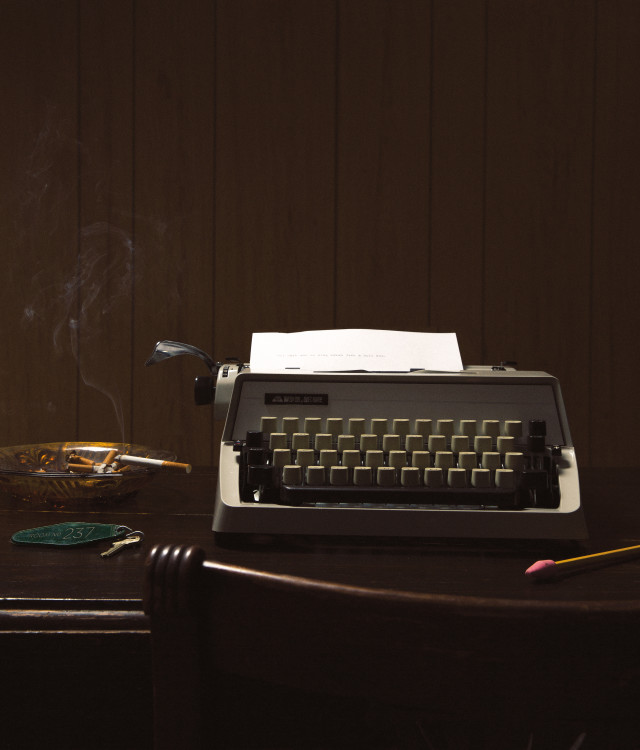

Incredible Fall Looks Inspired by Stanley Kubrick's The Shining

Image: Holly Andres

ON WENDY: Lizz Basinger bent dart jumpsuit, $229 at lizzbasinger.com; vintage 1970s suede coat, $220 at Vintalier; Woolrich Mustang western heeled boot, $260 at the Annex

ON JACK: Woolrich zip chino pant ($95) and Mountain Range crewneck sweater ($195), both at Animal Traffic; Cascade oversize scarf in burgundy polka dot, $64 at Bridge & Burn; Woolrich Yankee boot, $300 at the Annex

ON DANNY: Appaman chino pant ($52) and plaid flannel ($52), Krochet Kids International Becks Jr. snowflake hat ($32), Herschel Supply Co backpack ($44), and Plae Lou suede shoe ($68), all at Black Wagon

Image: Holly Andres

Gymboree T. rex sweater, $11 at Hoot-N-Annie; Pediped Josh tennis shoe, $29 at Mako; Baby Gap plaid roll tab shirt ($9) and J. Crew Crewcuts gray corduroy pant ($13), both at Small Fry

Image: Holly Andres

1950s chiffon pale pistachio party dress ($248), 1950s boatneck seafoam party dress ($198), and vintage brooch in hair ($98 for brooch/earrings set), all at Xtabay

Image: Holly Andres

ON DANNY: Mako hand-knit sweater, $44 at Mako

ON WENDY: Michelle Lesniak Weather Worn collection blouse ($258) and overall plaid dress ($348), both at michellelesniak.com; Barrow Equinox studs ($40) and Scarab pendant ($75), both at barrowpdx.com

Image: Holly Andres

ON JACK: Clinton flannel shirt ($118) and Roark pant ($108), both at Bridge & Burn

ON WENDY: Reif Haus burgundy sweater dress ($215) and “swacket” ($264), both at reif-haus.com; Polaris Mini Octahedron necklace, $60 at Charming the Moon

Styled by Eden Dawn

Photographs by Holly Andres

Assistant Stylist Kailyn Bowen Marcus

Hair & Makeup Kelly Peach

Asst. Hair & Makeup Sheri Mendes

Prop Builder Emily Wyant

Crew: Nolan Calisch, Nicolle Clemetson, Alicia Gordon

Models Wendy: Tess Holenstein (Sports & Lifestyle Unlimited); Jack: Kendall Wells (Q6); Danny: Tennessee Martine; Twins: Skye Velten

For more on how this shoot came together, check out the behind-the-scenes story and videos.

Oregonians love The Shining. But can we really claim it?

By Shawn Levy

Image: Holly Andres

Does The Shining stand the test of time? Yes. Thirty-five years after the words “Red Rum” first froze the blood, Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 masterpiece remains chilling and evocative. But does it belong to Oregon? That one’s harder to answer. Timberline Lodge’s cameo as the fictional Overlook Hotel has landed the Stephen King adaptation on many a shot-in-Oregon list. And yet, in the film’s two hours and twenty-odd minutes, Timberline appears—for sure—just four times. (A few more shots that may be Timberline are obscured by a blizzard.) They’re postcard images: the historic hotel and Hood’s summit against a mountain sky, about as Oregonian as it gets. But these shots constitute a combined total of about 30 seconds of screen time, and contain no dialogue or action.

Kubrick didn’t even shoot them. It turns out the acclaimed director was in England when the Oregon shots were filmed. (Born in New York, he moved to the UK in the early ’60s and rarely left). A second unit, with a deputy director, visited Mount Hood for the Timberline shots.

Kubrick did direct Jack Nicholson and Shelley Duvall in front of a replica, built at Elstree Studios near London, that lacked the hotel’s central tower. Ironically, on the inside, Kubrick’s Overlook is massive: a Pentagon-scale maze of corridors, ballrooms, guest rooms, and offices, far too big for its walls and bearing no resemblance to the Oregon original. The real Timberline embodies the Northwest inside with wood beams and floors surrounding a fireplace bigger than some new Portland condos. Kubrick’s Overlook is—appropriately for the story’s Colorado setting—more Santa Fe than Government Camp: buffalo heads, Navajo- and Apache-style rugs, and art that couldn’t be more out of place in the Cascade Range.

Somehow, as Nicholson unravels and Duvall shrieks and the snow piles up outside, The Shining feels—at least to an Oregonian—very true to the Northwest experience. A family drives westward with their hopes, fears, and possessions, more than a century after the blazing of the Oregon Trail but still an emblem of settlers’ wildcatting spirit. Then, in deep winter, claustrophobic mania settles in. The Overlook’s manager specifically references “cabin fever” as he warns the new arrivals about their impending isolation; Oregon pioneers didn’t invent that form of crazy, but surely they knew it well. There’s that weather, a mountain of it, trapping the Torrances indoors and dominating their moods in a way that any survivor of a soggy January in the Willamette Valley can appreciate. And there’s also a hint that the Overlook is cursed, haunted by the genocidal expansion of Europeans across the continent. Yes, this could be a theme of any film set in the West, but The Shining’s undertone of deep historical guilt certainly resonates in Lewis and Clark’s destination.

Timberline Lodge plays itself, more or less, in only one film: Hear No Evil, a 1993 potboiler. A few films have used Mount Hood to depict the Old West (Bend of the River, 1952), war-torn Korea (All the Young Men, 1960), and Shangri-La (1973’s musical Lost Horizon). None of these are celebrated as Oregon cultural landmarks. So why is The Shining feted as such? Maybe stars Nicholson and Scatman Crothers get some sort of bonus points in our collective consciousness for appearing, a few years before, in Milos Forman’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, shot in Salem and Depoe Bay—and a serious contender for the title of the best film ever made here. The Shining is a candidate, too, but of a special kind. Shot in Oregon? Maybe not. An Oregon film? Definitely.

Shawn Levy is a Portland critic and author, most recently, of De Niro: A Life. He is currently at work on a cultural history of Rome in the Dolce Vita era.