Behold, an Oasis

The Columbia Slough

ABOUT 20 YEARS AGO, when a handful of intrepid explorers began paddling the Columbia Slough, most people considered them 1) weird and 2) practically suicidal. At the time, the 18.7-mile slough, which runs roughly parallel to the Columbia River from near Gresham through North Portland, was no place for a boater. Its waters had become a dumping ground for urban offal: junked cars, rusted refrigerators, scores of tires, and shopping carts. All of it was lodged in the muck. Into the slough, too, went Portland’s sewage, which spilled, untreated, through 13 overflow pipes after a heavy rain. “There used to be rafts of algae that stunk to high heaven,” says Ry Thompson, a former environmental specialist for the Columbia Slough Team at the city’s Bureau of Environmental Services.

Thompson and I have just launched our canoe from a small dock at Whitaker Ponds, a public park where the nonprofit Columbia Slough Watershed Council also makes its headquarters. Before the group moved into the little white house there in 1996, the plot of land—located on a gritty part of NE 47th Avenue near the airport—was one of the slough’s many illegal dumping sites. But after volunteers hauled out the tires, cut back the blackberry vines, and replanted the banks, Whitaker Ponds became an oasis in miniature, home to bufflehead ducks, egrets, and Western painted turtles.

This middle stretch of the slough isn’t pretty, what with the parking lots ringed by razor wire, the warehouses visible through the trees, and the occasional plastic bag floating by. But I like how human-made artifacts butt up against the natural world in surreal ways: A goose eggshell bobs in the current alongside a golf ball lost by a player at Broadmoor Golf Club; a juvenile raccoon curls up in an old pipe.

“There’s one of the combined sewage overflows,” Thompson says, pointing to a pipe jutting from the bank. Once a point of exit for whatever Portlanders decided to flush, the overflows were shut down as part of the Big Pipe Project in 2000 (excepting a couple of spills since). That eliminated the brown plumes that gushed into the slough after a heavy rain, but the pipes remain as concrete reminders of the city’s less-than-green recent past.

A juvenile raccoon takes refuge in a small storm-water pipe protruding from the slough’s banks.

What is perhaps most striking about our paddle is the very existence of nature in such urban environs. It proves how much “wildness” a city can actually contain—not just in settings like Forest Park, but also in places like this, a strip of water coursing through a flatland ruled by boxy buildings. “Hear that fitz-pew sound? That’s a willow flycatcher,” says Thompson, noting that the slough provides habitat for neotropical migratory songbirds.

Not every segment of the slough is so industrial. Last July, I joined about 300 other paddlers for the annual Columbia Slough Regatta, in which the watershed council invites the public to explore a few miles of this hidden waterway. This year’s was held at the Big Four Corners region, the two miles or so that spill from the slough’s headwaters at Fairview Lake. That day, families in canoes, couples in kayaks, and local politicians dipped their paddles in waters where cottonwood and cedar trees line the banks and where sedges grow thick in the wetlands, providing nesting grounds for red-winged blackbirds.

“The waters in the Columbia Slough are so much cleaner than you think,” I heard a volunteer quip to a woman who’d asked how safe it really was. In fact, the watershed council likes to tout that the slough is cleaner than it’s been in more than 80 years. When I ask the council’s executive director, Jane Van Dyke, how that came to pass after decades of abuse, she pauses. “Well, there are so many reasons,” she says, before listing the Clean Water Act, the Big Pipe Project, the half million trees that have been replanted, and changing attitudes about the slough’s ecological value. This last point may be the most important one. The work to correct the damage here began in earnest only in the early 1990s. And as Thompson pointed out to me: “We still have a few decades to go.”

One of the many bridges that crosses the slough.

Explore the Slough

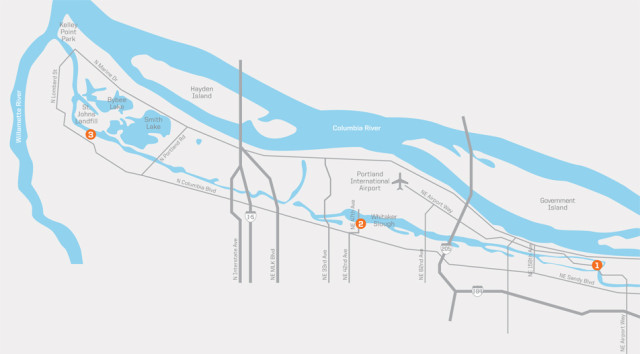

Big Four Corners

One of the most spectacular natural areas of the Columbia Slough, this two-mile stretch is edged by cottonwood forests and wetland meadows, and culminates at Fairview Lake, whose shores are ringed by large homes. Once you’ve put your boat in, head in the direction of the bridge. Soon you’ll be paddling a narrow channel, where the chorus of Bullock’s orioles is interrupted only by the whoosh of the occasional plane cruising overhead. (Launch: Enter at 16550 NE Airport Way. Across from NE 166th Avenue, look for the 40-Mile Loop sign and pull into the parking area; the trail to the dock is on the southeast side of the lot.)

Middle Reach

While it wouldn’t be considered “pretty,” what with the warehouses and chain-link fences, this stretch of the slough takes you into North Portland’s urban underbelly. But the middle reach isn’t all concrete and steel: You’ll inevitably spot great blue herons, kingfishers, and other creatures that make the slough their home. For a quick urban tour, launch from the Whitaker Ponds (you’ll find the path leading down to the slough on the left-hand side of the parking lot) and head toward the bridge. After 2.5 miles or so, you’ll reach the headquarters of the Multnomah County Drainage District (and one of the dams it manages—your cue to turn your boat around). (Launch: Whitaker Ponds, 7040 NE 47th Ave. Park along NE 47th Avenue.)

Lower Reach

It’s a bit of an adventure just finding the boat launch for this trip, which takes you from the junkyards of North Portland all the way to the Willamette River. (Across from Chimney Park on N Columbia Boulevard, you’ll have to locate the unmarked old St. Johns Landfill Road, cross the railroad tracks, and just before the locked gate, bear left on a gravel road.) The slough passes the landfill, now capped and covered with grass, and also connects to the signed North Slough, which is worth a side trip—the ash bottomland forest it winds through is often teeming with birds. Head all the way into the Willamette River (not recommended for novice paddlers) and you’ll be next to Terminal 5, where hulking cargo ships get their fill of grain. (Launch: 9363 N Columbia Blvd)

GET INVOLVED: To print out a paddler’s map of the slough, or to join regular paddle trips and volunteer cleanups (held the second Saturday of each month), go to the Columbia Slough Watershed Council website.

GREEN CANYON After it rushes headlong from the Coast Range, the 80-mile-long Tualatin River meanders more slowly through veritable canyons of trees.

Smith and Bybee Wetlands

It’s early August, and water levels at the Smith and Bybee Wetlands Natural Area are so low that to reach the edge of Smith Lake from the canoe launch just off N Marine Drive, we have to haul our kayaks through 80 yards of shoe-sucking mud. But we’re lucky to be paddling at all. Had it not been for 2008’s heavy rains, says Troy Clark, the mustachioed co-founder of Friends of Smith and Bybee Lakes and my guide for the day, this place would be a mudflat by now—great for shorebirds, but not so much for boats.

Our small flotilla of kayaks pushes off, and soon we’re breaking up schools of fish that leap around our bows, heading across the water toward the hills of Forest Park in search of the channel that leads to neighboring Bybee. At 2,000 acres, Smith and Bybee may be the largest freshwater wetlands inside a city’s limits in the United States. Each winter the lakes fill with water, and each summer they drain completely—part of their natural hydrology. At least, Clark says, that’s what occurred until 1983, when the Port of Portland installed a dam that turned the wetlands into what Clark calls “two warm-water reservoirs.” Which was not so good for the birds that hunted in the mudflats, but was a boon for another species: carp.

“This place was seething with them, just seething,” Clark says. “You’d see them roiling on the banks, writhing in the mud.” The carp devoured most of the aquatic plants, including the rafts of smartweed that provided habitat for ducks. As a result, the duck populations dwindled and the shorebirds stayed away. In essence, it was your basic man-made, domino-effect, mini-eco-disaster started by a dam.

But in 2004, Metro and the wetlands conservation group Ducks Unlimited replaced the dam with a “water-control structure” with four culverts that could be opened and closed. For the first time in 25 years, water flowed in and out of Smith and Bybee with the seasons. Soon after, the carp population dropped—they can’t survive the low-water summer months, and gates on the culverts prevent their return in winter. A few bunches of smartweed have since cropped up. Willows and wapato are growing in areas once underwater. Shorebirds like long-billed dowitchers are back, and wintering waterfowl have arrived in larger numbers to feast on the seeds of plants re-emerging after years of submersion. It was your basic man-made, domino-effect, eco-recovery that started with a dam’s removal.

Smaller than the great blue herons often seen on the Tualatin River, the green heron is identified by its glossy greenish cap.

As if sensing that Clark’s tale is one of hope for the natural world, birds begin to arrange themselves in avian dioramas around us: Alabaster egrets appear as statues in the distance; a trio of cinnamon teals jets from the water’s surface. Clark, a birding nut (he’s been conducting weekly bird counts in the area for 15 years), cannot contain himself: “A great blue heron and a green heron in one tree! Now this is a great day!” Each year the wetlands host more than 100 species of birds, he tells us.

And yet that doesn’t mean that Smith and Bybee is restored. Soon after we enter the channel, the water disappears under a shaggy carpet of green. “This is the parrot-feather I told you about,” Clark says. I drop behind him as he uses his paddle like a shovel, pushing the weeds out of the way and creating an opening just wide enough for our boats to inch through.

A waterborne plant with wispy leaves that swirl around a stem, parrotfeather is a favorite of aquarium enthusiasts. But it’s also native to the Amazon River, a fact that makes it an intruder to Smith and Bybee. Clark first noticed the stuff on a paddle five years ago, and like the carp before, it bred like crazy, choking out native plants. It’s one of 15 or so nonnative plants, along with purple loosestrife, reed canarygrass, and others, that his group has identified. To deal with the problem, he’s hoping that Metro will create a map of the invasives and develop an eradication plan.

Clark makes the point that the value of Smith and Bybee has only increased as other parts of the Columbia River’s south shore disappear. Some 90 percent of the area’s wetlands are kaput, their waters packed with dredge spoils (or garbage, in the case of the St. Johns Landfill). Clark knows that the wetlands will never be what they were 150 years ago: “I try not to think about what it looked like then,” he says. But at least they’re no longer perceived as useless swamps, impediments to progress, problems to be “fixed.” Today progress means managing the wetlands so that they approximate their original, natural state. And “fixing” Smith and Bybee means undoing some of what’s been done before.

Explore the Wetlands

Smith and Bybee Wetlands Natural Area by Boat

Even nonbirders will be dazzled by the sight of thousands of waterfowl, including American widgeon and Northern shovelers, that arrive at Smith and Bybee Wetlands come winter. Water levels won’t be high enough for paddling until the serious rains hit again in mid- to late November, but no matter: Since the drizzle and chill keep most boaters away, you’ll likely be left alone to slice through the water close to the flocks, an experience that just might make you appreciate the arrival of our most maligned season.

To locate the channel connecting the two lakes, turn your boat approximately 30 degrees to the right after pushing off from the Smith Lake launch site and head toward the electrical towers in the distance. As you cross the lake, keep a close eye on the right-hand shore, where you’ll eventually spot the narrow opening. To return to the boat launch, point your craft toward the blue-and-white water tower once you’ve re-entered Smith Lake. (Launch: To reach the park entrance, take I-5 to Exit 307 and go west on N Marine Drive for 2.2 miles. From here, road signs will direct you to the canoe launch at Smith Lake.)

Interlakes Trail

You’ll hear the birds before you see them on this easy, half-mile-long paved trail that starts near the wetland area’s parking lot. That’s because the path runs first through a shady forest of black cottonwood and Oregon ash that obscures any view of the wetlands (or the mudflats, depending on the season). No worries. You can ogle the birds as long as you like at the two observation decks. Be sure to bring your binoculars, though—the platforms are far enough away from the birds that they appear as specks fluttering on the water. Note that dogs and bikes are not allowed on the trail.

Group Outings

If you actually want to know the names of the waterfowl and raptors that arrive en masse this month, consider signing up for a walk with Metro’s gabby and knowledgeable naturalist James Davis. On October 4 and 25, he’ll lead walking tours through the wetlands and teach you about everything from the migratory patterns of geese to the nocturnal habits of minks and muskrats. Metro will even provide binoculars for amateur birders. (Free, though reservation required; www.oregonmetro.gov; 503-797-1850 option 4)

The Tualatin River

We’re only a hundred paddle strokes west of the 99W Bridge, not far from the 25,000-person city of Tualatin, but already the sound of tires rolling across concrete is fading. En route to wine country, I’d often glanced down at the Tualatin River from my car window, but this is my first time on the water itself. Already the experience is showing me that Washington County is not merely an agricultural region marred in parts by suburban sprawl.

Here the river is wide and meandering, bordered on both sides by tall trees whose canopies shade a thick understory. It’s a fine backdrop for the kingfishers flitting about. “This really is what the river should look like,” says Sue Marshall, who served as the executive director of the nonprofit water conservation group Tualatin Riverkeepers from 2000 to 2006, and who remains an avid volunteer. Save for a few twigs and leaves, the water’s surface is glassy, and the hot summer air is just as still. It isn’t hard to imagine a child clinging to the end of a rope swing suddenly appearing from the woods and landing near the bow of my kayak with a cannonball kersplash.

A few decades ago, that might well have happened, Marshall tells me as we pass the former location of Roamer’s Rest, a recreational spot on the banks where, in the 1950s, families would gather for picnics and kids would careen down slides into the water. But after articles about the polluted water began appearing in the Oregon Journal in the mid-1950s, the Tualatin became known as the most polluted river in Oregon. When the state health department posted advisories warning people against swimming in the river, it didn’t seem like such a fine place to cool off anymore.

The reasons for the problems were numerous. State permits had allowed area farmers to siphon off too much water, leaving the river stagnant and shallow during summer months, which made it inhospitable to aquatic life. (“They darn near sucked it dry,” Marshall says.) Even worse, as the population of Washington County increased, so did the volume of human waste, and the Tualatin and its tributaries became the dumping spot for some two dozen sewage-treatment plants (where not much “treatment” occurred).

“Some seniors have told me stories of coming home with infections after swimming in the river,” Marshall says. It may sound a bit uncharitable, but there’s no getting around the truth. The Tualatin had become a bit of a cesspool. There were reports of platoons of dead fish clustered along the banks.

But if the river has a permanent place in the history of how Oregon mucked up its waterways, it’s also a testament to how a river can be redeemed again. Thanks to a local bond measure in 1970, those treatment plants were consolidated into a few facilities, all of which were outfitted with state-of-the-art sewage-treatment controls. And after the Portland-based Northwest Environmental Defense Center filed a lawsuit against the EPA in 1986, compelling the agency to enforce the 1972 Clean Water Act on the Tualatin, the river became the country’s first to receive what are called Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) standards. In spite of the wonky name, TMDLs are an essential part of water regulation. They set the maximum amount of particular pollutants a body of water can contain to meet the standards of the Clean Water Act; today they’ve been applied to some 20,000 bodies of water.

The results of these improvements, among other cleanup efforts, are clear. Today the Tualatin meets nearly all of its TMDL standards (though the river is still too warm, which can inhibit fish breeding patterns), and people are returning to the river for recreation once again.

When I met Marshall at Tualatin Riverkeepers’ offices, the first thing she handed me was a list of potential launch sites for the Tualatin River Water Trail, the 35-mile paddling route the group has been developing since 1995. Like many other water-conservation groups, Tualatin Riverkeepers has realized that one of the best ways to protect rivers is by getting people back out on them.

After the Tualatin’s reputation was sullied, “people turned their backs on it,” says Marshall, who occasionally swims in the river with her family (though not after a heavy rain, when large volumes of storm water and agricultural runoff flow in). The water trail is one way to bring people back to its shores. “Unless people feel a connection and experience their waterways, there’s less of a stake in cleaning them up.”

Explore the River

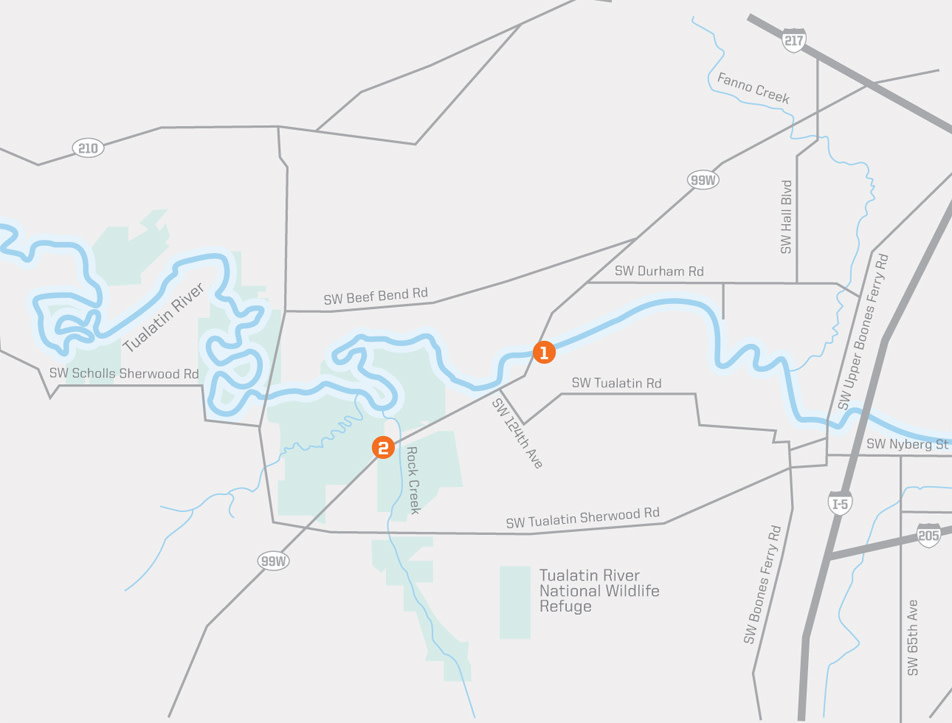

99W Bridge to Schaumberg Bridge

This stretch of the Tualatin River is so lazy that you may wonder whether it’s moving at all, and you definitely won’t notice that you’re paddling upriver (which makes it perfect for beginning paddlers). Other than a few small piers and homes here and there, you’ll course through a verdant landscape of cottonwood, alder, and cedar. (Blue-and-white mile-marker signs along the river tell you how far you’ve gone.) Later this month is an ideal time to take this trip, as leaves fall from the overhanging trees onto the water’s surface, creating a patchwork of crimson, orange, and yellow. (Launch: To reach the boat ramp, turn south onto SW 124th Avenue from 99W, turn left on SW Tualatin Road, left on SW 115th Avenue, and left again on SW Hazelbrook Road. Look for four parking spots on the side of the road near the marked put-in. The small dock is just beneath the 99W Bridge.)

Tualatin River National Wildlife Refuge

Some 17 years ago, a group of citizens in the rural hamlet of Sherwood wanted to re-establish some of the area’s wetlands, many of which had been lost to agriculture and development. Numerous hard-fought battles later, the Tualatin River National Wildlife Refuge now encompasses some 1,300 acres—though it may one day hold as much as 4,000. Explore the 400 acres open to the public (and its excellent visitors center, which opened last spring), and you’ll see how a former dairy farm is being transformed into prime habitat for birds. This month marks the beginning of the wintering birds’ return, when thousands of waterfowl, such as cinnamon teal and Northern pintail, flock to the wetlands. Hit the flat one-mile path bordering the wetlands in early morning or near dusk for the best bird-viewing. Binoculars are a must. (503-625-5944; 19255 SW Pacific Hwy; www.fws.gov/tualatinriver)

GET INVOLVED: You can download a paddler’s map of the Tualatin River from the Tualatin Riverkeepers website (www.tualatinriverkeepers.org), where you can also learn about paddle trips and volunteer events. To help out on the Tualatin Refuge (whether by staffing the visitor center or planting trees), contact the nonprofit Friends of the Refuge (503-625-5944 x227; www.friendsoftualatinrefuge.org).