Paradise Ross

ON A CHILLY DAY in early winter, a flat-bottomed skiff informally known as Simplicity cruises northward on the Willamette River from her launch in Sellwood. Thanks to post-Christmas snowmelt and winter rains, the river looks swollen and greasy, its milky, coffee-colored waters studded with floating deadwood. The kayakers, rowing teams, and powerboats that often turn this stretch of water into an aquatic playground are absent, leaving Simplicity to make a lonely chug toward Ross Island.

“Ross Island” is the collective name for a teardrop-shaped complex of four small islands—East, Hardtack, Toe, and Ross—that jut out of the Willamette just south of downtown. As we approach the islands’ southern reach, the shallow channel between East and Hardtack opens before us, bordered by dense, winter-barren cottonwoods and ash trees on either bank. With the glassy spires of the South Waterfront’s condo towers and downtown’s office high-rises looming in the background, this narrow passage looks like a portal to a lost world—some mossy, austere, primeval Northwest, unsullied by the dread fingerprints of man.

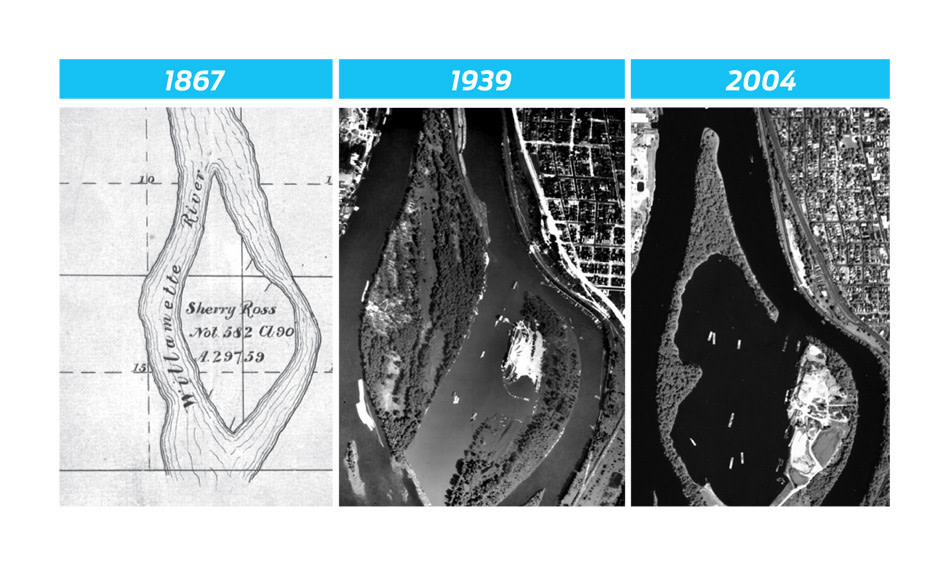

Ross Island’s history, however, is actually a dense collage of human intervention. A century ago, East Island did not exist. Likewise, Ross and Hardtack islands, now a unified wall of trees off the boat’s port side, were once separate. In 1927, the Army Corps of Engineers linked them with a skinny artificial land bridge that closed off the islands’ main channel. This rerouted the water flow so dramatically that a new silt deposit began appearing on maps soon after construction. The protuberance eventually grew into East Island, the lumpy quadrilateral of gnarly vegetation I see today. Meanwhile, poor Toe Island, once respectable enough, was whittled into a sad little rocky atoll that sometimes disappears beneath the waters completely.

As a complex, the island today is a strange combination of postapocalyptic wasteland and woodsy, rustic preserve. It’s festooned with hulking, corroding equipment and choked by invasive plants. Yet nature remains a partner in the island’s evolution in the form of a steady stream of visiting eagles and herons, deer and coyotes. It is this paradoxical capsule of wildness secreted in the city’s heart that the man standing next to me aboard Simplicity, Mike Houck, believes can become a green-urbanist gem of national, even worldwide, significance: a water-bound natural habitat as priceless to the lives of critters and the emotional well-being of humans as Forest Park.

“In this reach of the river, this is the most significant conservation opportunity we have,” Houck says. “And from a national perspective, I can’t think of another city that has anything like Ross Island in the heart of [it].”

Houck’s vision is simple enough. Ross Island sits just offshore from the 160-acre Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge, which Houck played a key role in creating in 1970. If combined into a single park, Oaks Bottom and Ross would amount to about 460 acres, or half the size of New York’s Central Park. A riparian refuge of that size would instantly become one of the world’s premier urban wildlands—over four times bigger than London’s Wetland Centre, which claims to be “the best urban site in Europe to watch wildlife,” for example. As an act of postindustrial reinvention, a revitalized Ross would rank alongside New York City’s transformation of the vast Fresh Kills landfill into a park-cum-nature reserve, a process that took 30 years.

But any restoration would also require an epic series of political, environmental, and engineering feats, likely stretching far into the future. For decades, the Ross Island Sand and Gravel Co ran the islands as a private industrial fiefdom, gouging out gravel to produce the concrete that built much of downtown Portland. Besides shearing off whopping chunks of the islands themselves, this mining past created a present-day regulatory tangle involving multiple tiers of government and a sometimes-obdurate company that still uses the islands as its primary factory. Add in feuding recreationalist factions—powerboaters and kayakers, two watery tribes who spar over wake zones and noise rules around Ross—and three different property owners, and some picture of the islands’ complicated status emerges.

Still, as I stand aboard Simplicity—with the silent islands on one side and a young bald eagle soaring above—it’s hard not to find Ross beguiling. If nothing else, a visit to this strange world fires the imagination.

Arguably no single person has shaped more of Portland’s landscape than Mike Houck. Ross Island is next in his sights.

This morning, Houck looks nautical and intrepid with his white goatee, flat tweed cap, diamond-stud earring, and signature fox-sly expression. During the past four decades, perhaps no single person has affected Portland’s landscape more significantly than he has. Though Houck is little known locally outside the wonky communities of politicians, planners, and activists, he has chalked up numerous national and international commendations. This month, the Garden Club of America will present him with another: the Frances K. Hutchinson Medal, an honor he’ll share with the likes of historical environmental heavyweights such as Rachel Carson, Stewart L. Udall, and Lady Bird Johnson.

Fusing a genteel understanding of his native city’s green sensibilities with old-fashioned, often heavy-handed agitation (his every e-mail signs off with the slogan “Endless pressure, endlessly applied”), Houck’s rakish approach and salty vocabulary call to mind an outback environmentalist in a timber-town barroom. But he is also an unabashed urbanite. He coined the title “urban naturalist” for the Audubon Society job he invented for himself in 1980, which he still fills part time. In 1999, he established his own organization, the Urban Greenspaces Institute. From that pulpit he has played strategic roles in issues ranging from Metro’s 2006 natural areas bond measure to getting greens, farmers, developers, and local officials to agree on a 50-year growth plan for the metro area.

But bobbing in his boat on Ross’s eastern side, far away from meeting rooms and negotiating tables, Houck takes a simple naturalist’s delight in spotting the surrounding wildlife, and, with his polyglot’s vocabulary of bird calls, often talking to it, too. “Common mergansers, couple of ’em,” he says. “And check out the GBH”—birder shorthand for the great blue heron standing stolidly on a distant bank.

Houck has been thinking about Ross Island, in one way or another, since 1970, when, as a grad student at Portland State University, he lobbied City Council to protect Oaks Bottom. In 1988, he wrote the management plan for the area. (Houck collaborated on the plan after he posted his own homemade signs declaring the Bottom a “wildlife refuge,” a designation that was soon picked up by local newspapers.) This long and personal history makes him an expert on this small stretch of river—and probably the individual most invested in bending Ross Island’s future to his will. To that end, Houck and some allies, gathered under the ad hoc banner of the Friends of Ross Island, stand determined to propel the islands into the public consciousness.

“We don’t see a comprehensive plan coming from anyone else anytime soon,” Houck says. “We see our job as taking the bull by the horns on this thing.”

This effort is just the latest chapter in the long—if scattershot—history of a place that, despite being in the center of the city, has never quite found its place. A man named Ross first claimed the islands as a homestead in 1850. In the latter days of the wild frontier, a Ross distillery cranked out Blue Ruin whiskey, “a fluid of high voltage.” Period accounts, unearthed by Portland Parks & Recreation planner Nancy Gronowski, describe Ross Island circa 1890 as an enclave of proto-beatnik houseboat dwellers, where “liberated ladies played ukuleles for gentlemen who recited poetry.” Stretch the imagination, and the island becomes an early incubator of Portland’s ever-blossoming bohemian scene.

Houck is hardly the first to see this offshore kingdom as a potential civic asset. The 1903 Olmsted Plan—the landmark scheme that sketched Forest Park, Mount Tabor, and much of the rest of Portland’s emerald necklace—described Ross as a future setting for field sports and pleasure outings. Portland’s first parks superintendent even drew up a proposal for the island featuring classical, formal gardens, à la Peninsula Park. Portland voters proved too cheap to buy the islands, however, leaving geology, hydrology, and industry to conspire.

The 40-meter-thick layer of gravel (Holocene alluvial gravel, if you want to get technical) that makes up the archipelago’s bedrock is a perfect ingredient in concrete. By 1926, a syndicate of connected local bigwigs—a member of the dock commission board, a powerful attorney, and a former governor—set up the Ross Island Sand and Gravel Co in a flurry of cozy deals with state and local regulators. (The dock commission, for example, issued the necessary building permits, while the state blocked a lawsuit aimed at stopping the company.) The company mined the center of the archipelago for the next 75 years, turning the former central channel into a deep, oblong lagoon.

In 1977, Robert Pamplin Jr., millionaire heir to a textiles fortune and a local power broker in his own right, bought Ross Island Sand and Gravel. Pamplin—whose other holdings and endeavors, past and present, include newspapers, radio stations, a Christian recording label, farms, vineyards, a Civil War museum, a ghost town in Eastern Oregon, and, according to his foundation’s website, the accumulation of more academic degrees “than any living American”—cuts a somewhat eccentric figure. His tenure with the island, at least so far, suggests he can’t quite decide whether to be a benevolent local patriarch or a reclusive, get-off-my-lawn tycoon.

Given the threatened species of salmon and steelhead that ply the waters surrounding Ross Island—the most undisturbed section of Willamette River within the city—Pamplin’s ownership of Ross puts him on the hook for water quality, species protection, and habitat restoration, not to mention the larger question of what will happen to the islands when his company no longer wants or needs its island factory. Over the past 30-plus years, Pamplin has conducted a marathon fencing match with city and state officials over the islands. Along the way, his management of Ross garnered so much negative publicity that he started his own newspaper, the Portland Tribune, largely to hit back at the Oregonian. (Pamplin, through a representative, declined to be interviewed for this story. Ross Island Sand and Gravel officials did not return calls.)

In 2002, Pamplin made a much-ballyhooed pledge to give a large portion of Ross to the city. Negotiations over the details broke down, however, and Pamplin rescinded the offer. This impasse continues to color public discussion of the islands, with Ross’s mercurial overlord often being perceived as the bad guy. And that might have been the end of the story, if Houck and other environmental advocates hadn’t initiated their own direct negotiations with Pamplin. The result: Ross Island Sand and Gravel donated 45 acres on the northern and western sides of Ross to the city in 2007. Not only did the gift give the public a firm toehold on the islands, but it also set the stage for the next act in the islands’ future.

“Too much has been made of what Pamplin originally promised,” says Bob Sallinger of the Portland Audubon Society, a leader within the Friends of Ross Island who was involved in the negotiations. “The clock didn’t stop in 2003. We need to look at the next big challenge, which is to get everyone who has a stake in the place to sit down together.”

Simplicity enters the island’s lagoon. Houck gestures out over the vast expanse of flat water. Cottonwoods, crumbling banks, and upturned, skeletal tree roots define the far shore. “When the lagoon was first formed [in 1979], it was 20 feet deep,” he says of our location. “Now it’s 130 feet deep.”

Our boat is a sturdy craft, with small decks fore and aft and a nifty, arched-roof cabin, complete with woodstove, in between. All the same, the thought of the man-made abyss stretching full-fathom 21 below us is slightly unnerving. A bitter wind blows. It’s Sunday, and Ross Island Sand and Gravel barges, heaped with debris, sit motionless in the water. On the east side of the lagoon, the company’s gravel-processing plant looms—gray, corroded, and deserted, like an artifact of post-Soviet industrial decay. The landscape feels more like the setting of an action movie’s climax than Portland’s next great park. Houck, undeterred, makes for the lagoon’s western bank.

Ross Island Sand and Gravel stopped excavating Ross eight years ago. Around that time, Houck joined city and Metro officials on an advisory board to review the company’s operations permit, which spells out many of its environmental obligations. The previous management guidelines, dating to 1979, had called for the eventual reconstruction—somehow—of the islands’ original contours. “We decided, well, if those are the terms, that’s never going to happen,” Houck says. “So we changed the agreement to say that they had to bring the shore out 15 acres and create a bunch of shallow-water habitat at the north end of the lagoon.”

Young salmonids need shallow water to rest and feed in as they migrate. Ross may be a mined-out husk, but for fish, it still has its uses, particularly when they face the long swim through the hard edges of downtown’s seawall and the Portland Harbor. As Sallinger explains, none of the work and money going into salmon restoration upriver will work as well if Ross isn’t also restored. “Once you get into the river’s northern reaches,” he says, “Ross is kind of the last gasp of natural habitat.”

So these days, the Ross Island Sand and Gravel barges are actually dumping dirt back into the lagoon to create a graded underwater landscape congenial to fish. A lot of the actual infill material comes from the nearby excavation of the Big Pipe, the $1 billion-plus super-sewer project that will reduce the amount of raw excrement that flows into the Willamette from Portland. Where Ross Island’s gravel once made the buildings and sidewalks of the city, the city’s plumbing system is now rebuilding Ross Island. But preliminary estimates suggest that the reconstruction effort will require 4.5 million cubic yards of material—the equivalent of the volume of the US Bancorp Tower, 50 times over. As if to amplify the ambiguity over whether Pamplin is an ally or an enemy, Ross Island Sand and Gravel has missed several deadlines to provide information about the work’s effect on water quality, to the chagrin of state and federal environmental officials.

The great blue heron is one of more than 100 species of birds that make a home on Ross Island.

Image: Corey Arnold

Simplicity pulls up along the lagoon’s western bank, an 80-foot-wide splinter of the original Ross Island that was donated to the city by Pamplin in 2007. Portland Parks & Recreation now manages the parcel and has begun what promises to be a long effort to eradicate nonnative plants. “It’s not the Garden of Eden,” Dave McAllister, the bureau’s city nature manager, says. “It’s a snake pit of invasive species.”

Right now, the Parks property, like the rest of the island, allows limited access to the island. (With one exception: up to the normal, seasonal high-water line, the banks are legally part of “the waters of the state” and, therefore, public. Someone recently erected a statue of Sasquatch on the beach.) But as Houck and his allies dream about the future, they’re giving a lot of thought to how Portlanders will eventually use Ross Island—and they’re focusing on what is sure to be a controversial look-but-don’t-touch concept of “access.”

“Maybe you don’t need to walk on the island,” Houck says as Simplicity bobs 20 feet from shore. “Maybe there doesn’t need to be a footbridge or trails.” Surveying the lagoon and seeing past its current state of creepy dilapidation, he fantasizes about barges anchored near the shoreline, equipped with bird blinds for a kind of industrial-scale, open-air natural history diorama. “People could come out in canoes or kayaks—you know, bring your picnic and … ” A huge adult bald eagle interrupts Houck, arcing over the boat and landing on a stark branch above us.

“See?” Houck says, picking up his train of thought with a wide smile. “Just that. Right there. Stuff like that never ceases to blow people’s minds.”

Up close, Ross is indeed an intriguing object example of ecological resilience: it’s home to a heron rookery and remains a way station for river otters, eagles, hawks, beavers, even coyotes. Bob Sallinger tells a story about standing at the river’s edge in the South Waterfront and, with his birder’s scope, seeing an antlered buck stride out of the woods on Ross’s northern end. Such things suggest that if human beings could sort out the many vested interests at play, these battered islands could indeed become something extraordinary: a hybrid habitat wherein nature serves the city and the city serves nature.

If Houck and his allies have their way, some version of this will come to pass. But when? The answer is not for the impatient. At the moment, Houck keeps a rough timetable of the next five years’ goals in his head, but he admits that a lot of its bullet points are aspirational. Next year, the Friends of Ross Island will put forth their final (and completely unofficial) plan for all four islands and the reach of the Willamette between the Sellwood and Ross Island bridges. (“Thus, we will do,” Houck says.) In three years, Ross Island Sand and Gravel’s operations permit demands the completion of a reclamation plan. But what next? Will the city and Pamplin’s company—so often at odds—find consensus on a plan for the islands’ future? And will that plan bear any resemblance to the Friends’ ambitious green-urbanist dreams? When will gravel-processing at that grimy factory cease? Will the public ever own all of Ross?

As Simplicity drifts beneath the eagle’s impassive gaze, Houck reflects, as is his wont, on the islands’ potential. “We could talk about what could happen at Ross in a 10-year time frame, and we should, but we could also talk about a 50-year timeline,” he says. “People might say, well, hell, 50 years is a long time. I, personally, have already been involved in Ross Island for 31 years. Fifty years is not a long time in the scheme of things.”