The Next Wave

For more than three decades, Bob Eder has tracked the patterns of crabs.

From where the youngest ones congregated during the previous season to how the weather and currents affect their migration, Eder has tuned his intuition like radar to find the choice spots for the 500 crab pots he places 20,000 times throughout the season.

Considered by his peers to be one of the Oregon Coast’s top crabbers, Eder does not fit the profession’s crusty caricature. Originally from Southern California, he became, at 21, one of an increasingly rare breed—a first-generation fisher. At 59, tan and youthful in his Tevas, T-shirt, and button-down shirt, he’s at once pensive and playful as he struggles to find words to describe his love for capturing crustaceans. Fishing, he explains, is a way to connect to the world. “It’s powerful and humbling to pull up traps full of life. I’ve pulled up hundreds of thousands of pots, and it never ceases to move me.”

To make that connection, he’s faced hair-raising waves crashing broadside into his boat and fetched far-flung crab pots carried miles by winter storms. As he recounts his adventures, it’s instantly evident why Eder is such a good fisherman. He’s unflappable. As he speaks calmly and deliberately, pausing to carefully organize his thoughts, his eyes rarely stray from the harbor he calls home. The last of the hunter-gatherers, fishermen like Eder have long been the primary harvesters of ocean resources in Oregon. Crabbing is king: the most competitive, and, at $45 million in value last season, the most lucrative single-species fishery in the state. Eder has his favorite spots. So do the other 427 crab permit holders working the coast who, each year, drop a total of 112,000 pots into sandy-bottom stretches along the 363-mile Oregon shoreline.

Sitting in the sunshine on the deck of the Coffee House overlooking Newport’s Yaquina Bay, Eder explains that, to him, the hard-won knowledge of the best pot locations is as proprietary as BP’s geological reconnaissance for oil. “It is intellectual property,” he stresses, “albeit some may consider it a primitive form.” Yet he and many of his cohorts recently gave up their locations in an attempt to make peace with a soon-to-arrive neighbor: wave energy buoys. “We had the run of the range for a long time—that’s changing,” says Eder of the invader. “For lack of a better analogy, we are like the Native Americans watching the wagon trains coming into the valley.”

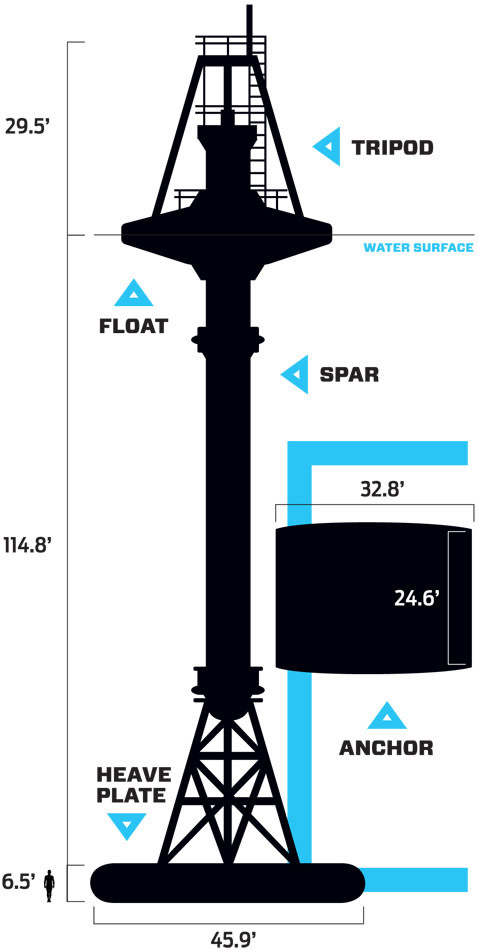

This spring, the New Jersey–based Ocean Power Technologies will anchor a massive 200-ton, 80-foot-tall, 40-foot-wide test buoy just off the coast north of Reedsport—smack in the middle of some of Oregon’s most productive crab grounds. If successful, the buoy could be followed by hundreds more in the form of large-scale wave farms that could hamper more than just crabbers. Whales could potentially collide with buoys or cables. Electromagnetic waves could disrupt fish or mammal navigation. And, if surf-powered devices like the 60-foot-tall mechanical oyster made by the Scotland-based start-up Aquamarine Power pursue a stake in Oregon, surfers may find fewer spots to ride the swells.

But rather than fight, Eder and many other Oregon fishers—along with a wide coalition of federal biologists, conservationists, and surfers—are now at the table trying to make what might be a bitter turf war into a radical experiment: applying the principles of the Oregon land use system to the ocean. It’s called marine spatial planning, and Oregon is one of only two states trying to comprehensively divide the sea into specific uses.

“Marine spatial planning borrows the terms and tools from land use planning, but it is something new and original,” says Paul Klarin, marine program coordinator at the Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development, the office charged with implementing our storied statewide land use laws. “We’re starting from scratch to figure out how to deal with wave energy, marine reserves, and any other future uses in the ocean.”

The process will be tested as Klarin’s team begins literally divvying up the ocean: searching first for the sites in the three-nautical-mile-wide strip of state-owned waters just off the shoreline that will be zoned industrial, for wave energy, or conserved with restricted fishing for marine reserves. ?“Every parcel of land is zoned for one or multiple uses,” says Astrid Scholz, vice president of knowledge systems at Ecotrust, a Portland-based nonprofit working on the project. “We’re moving in that direction on oceans.”

In the waters just beyond the sleepy coastal town of Reedsport, the Oregon way of ocean planning will soon get its trial by wave. Reeds-port Mayor Keith Tymchuk, for one, can’t wait. Sitting at Bedrock’s, a local restaurant owned by a former timber worker, the energetic mayor, who’s also a schoolteacher, describes his half-full classrooms—a stark reminder that tourists and retirees are the current lynchpins of coastal economies. The Great Recession isn’t to blame for shrinking the county from roughly 4,900 at its peak in the 1980s to just under 4,400 now, Tymchuk says. Nor for Douglas County’s 14.3 percent unemployment rate. No, Reedsport’s ongoing woes are deeply rooted in the demise of logging and milling. Attracting a new industry is key to restoring family-wage jobs. “Wave power,” says Tymchuk, “might be able to deliver jobs that would reinvigorate communities by encouraging families to move back here.”

As part of his two-term effort to grow green jobs in Oregon, Governor Ted Kulongoski began rolling out the welcome mat to wave energy companies in 2007. He created the lottery-funded $4.2 million Oregon Wave Energy Trust, a public-private partnership to support responsible development of wave energy, and he spearheaded and signed into law Senate Bill 838, which requires that Oregon meet 25 percent of its power needs with renewable energy by 2025. The trust’s goal is to install 500 megawatts of wave energy by 2025 to help meet that goal. The bait worked. By January 2008, eight companies and municipalities had applied for three-year preliminary permits to study the feasibility of wave energy along stretches of the Oregon coast. But well ahead of the pack was Ocean Power Technologies of New Jersey, which, having long eyed the potential of Reedsport, had applied for a preliminary permit for the nearby waters in July 2006.

Near the major port of Coos Bay, Reedsport sits in a particularly sweet spot for waves. Courtesy of a one-time paper mill just north of town, it’s already equipped with a substation. The old mill’s pipes—which once released up to 9 million gallons of treated liquid waste per day into the ocean—are another plus: they now can carry electrical cables pulsing with clean wave energy, thereby offsetting millions in development costs. When Ocean Power Technologies began hunting locations for a 10-buoy pilot project, Reeds-port was a no-brainer. Scheduled to be in place by 2012, the project, if successful, will be the first facility in the continental US to generate saleable power—1.5 megawatts, enough to light up roughly 1,500 homes.

But to Reedsport and other coastal communities, the jobs and fossil-fuel-free energy come with an unsavory catch. Oregon is providing the incentives for wave energy. Generally, states control their own natural resources. But the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) controls all energy development and, therefore, federal licenses for wave energy projects connecting to the grid. Those licenses can last between 30 and 50 years.

When Oregon’s crabbers found this out, they were stunned. “We’re not against wave energy. It’s all about location,” says Nick Furman, executive director of the Oregon Dungeness Crab Commission, based in Coos Bay. “We just don’t think that we should bear the brunt of its development because developers from New Jersey want to minimize investor costs.”

What’s more, the 10-buoy project is merely the start. Two years ago, Ocean Power Technologies unveiled plans for a 100-buoy array near the paper mill north of Reedsport and up to 200 buoys off the coast of Coos Bay. Together, the two arrays would fill one-and-a-half square miles of ocean with rows of generators, each the size of a 10-story building, with no plan in place guiding how to erect such a city in the sea.

Oregon iron works is fabricating Ocean power technologies’ first buoy, to be deployed this spring off the oregon coast.

Image: William Anthony

“When OPT came to Reedsport, it was like the martians had landed,” says Onno Husing, director of the Oregon Coastal Zone Management Association, a coalition of coastal governments. “Oregon is the mecca of statewide land use planning, and it came as a shock that there was nothing in place for the ocean.”

Kulongoski quickly responded to the community outcry, designating the Reedsport Ocean Power Technologies wave park for “Oregon Solutions,” a state collaborative emergency problem-attack program. (Past successes have included relocating Vernonia’s flooded schools and slashing costs associated with dredging the lower Columbia River.) But Kulongoski also invoked the capstone of Oregon’s land use planning system—public involvement—by brokering a landmark memorandum of understanding between the state and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. The agreement bought time for the state to develop policies for locating and operating wave energy facilities. But, more important, the memorandum mandated that fishing and environmental interests be considered, and gave the community a voice in where the wave energy installations would go.

“Like the bottle bill or public beach access,” says Scholz, “this is one of Oregon’s pivotal contributions to public law.”

With equal loves for the ocean, coastal communities, and the law, the Oregon Coastal Zone Management Association’s Husing found himself acting as architect of a marine spatial plan. Clean-cut and articulate, Husing has a subdued countenance that belies his flair for dramatic depictions of events. He describes the rash of preliminary wave energy permits in 2007 as the “gold rush.” He’s chronicled wave energy’s every ebb and flow in a series of newsletters on the association’s website. Steeped in marine policy for over 30 years, Husing produced the second state ocean policy study in the country while still in law school at the University of Oregon; it led to what would become Oregon’s Ocean Policy Advisory Council (OPAC). During the last three years, the natural-born negotiator has deftly brought the fishers to the bargaining table.

Oregon, according to Ocean Power Technologies’ Robert Lurie, enjoys the best conditions for wave energy generation of any place in the continental United States: Our coast’s waves are tall, frequent, and consistent. Transmission lines run along the entire coast. And no significant physical barriers (like major mountain ranges) stand between the buoys and the largest population centers. OPT’s first buoy, manufactured by Oregon Iron Works, will be deployed this spring. If it works as planned, its peak generation will be 150 kilowatts.

Husing understood the only way to protect the fishing grounds was to reveal where they lie. So as fishers began organizing into collectives such as Fishermen Involved in Natural Energy (FINE) and the Southern Oregon Ocean Resource Coalition (SOORC), Husing was searching for ways they could confidentially share their fishing data in order to hold onto their prime grounds. His efforts ultimately helped secure funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to hire Ecotrust, a Portland-based nonprofit, to record and map fishing data. Ecotrust had previously worked directly with California fishers to bring their sensitive data to the negotiating table to create California’s new network of marine protected areas.

Husing recalls the fishers’ wariness of any kind of “eco” group. Trust was key. It took about six months to convince the first of the 500 Oregon fishers interviewed over the last year to reveal their grounds’ locations. Some, like the recreational fishers affiliated with the Fishermen Advisory Committee for Tillamook (FACT), resisted sharing their data with Ecotrust, fearing it would be used for pro-marine-reserve purposes. But ultimately, they, too, joined in helping to create a momentum of growing public involvement, which brought Ocean Power Technologies to the negotiating table as well.

In August, the company signed what the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission calls a “settlement agreement” with crabbers, surfers, environmentalists, and state and federal agencies—in short, anyone who could bog the process down. The terms: neither government agencies nor activists would fight Ocean Power Technologies’ 10-buoy demo project, and in exchange, the company would submit to a 263-page adaptive management plan for any further expansion of the project.

“Rather than risk future lawsuits, and to be more in tune with the Oregon way,” says the company’s Portland-based public affairs consultant Leonard Bergstein, “Ocean Power decided it would be most productive to pursue a settlement agreement.”

After four years of meetings and tough negotiations, the deal brought everyone to the point of taking a deep breath and seeing how wave energy plays out, according t0 Reedsport mayor Tymchuk. “I like to think of what we’ve done in terms of Lewis and Clark,” he says. “The wave energy permitting process was a trail that had to be blazed—and it takes a pioneer spirit willing to go first and hash it out to make it work.”

The unorthodox approach set a hefty precedent for future wave energy development, but it also put an Oregon-based project in the lead for commercial-scale wave power in the United States. And that’s a fine tradeoff, according to Ocean Power co-founder George W. Taylor. “One of the positives about Oregon,” he notes, “is the enthusiastic and methodological way Oregonians deal with these planning issues.”

But the irony of this new, supposedly sustainable energy source facing such high scrutiny isn’t lost on some in the field. “Exxon doesn’t come in and have touchy-feely conversations with the community before they poke holes. They just do it,” says Jason Busch, executive director of the Oregon Wave Energy Trust. Pointing out that there will be many tough choices ahead as climate change likely worsens, he adds, “Wave energy has found a way to extract energy in such a way as to not overuse, yet we’re subject to the highest levels of scrutiny, while existing oil and gas activities cause climate change that threatens entire species.”

For all the various constituencies’ deep anxieties about wave energy—and the years of meetings to assuage them—the fact remains that nobody knows for sure how or if this new technology will even work. In 2007, headlines (“Oregon hopes to catch energy wave”) excitedly announced the launch of the first test wave energy buoy, developed by Finavera Renewables, off the Oregon coast. Two months after its deployment, and one day before its scheduled removal, more headlines revealed the ocean’s last laugh: “Test buoy for wave energy sinks off Oregon coast.” The Vancouver, BC–based Finavera has since abandoned its efforts in Oregon. Several other failures have occurred around the world.

Potentially dozens of entirely different designs by other companies in this new industry will soon follow here and in other ocean environments, from sea snakes tethered offshore to jetty-anchored stacks of slanted steel reservoirs designed to catch incoming waves. Currently, US Patent records show 713 patents for wave energy devices. However great the theories and simulations of each kind of buoy might be, they will still have to meet the force of the sea.

Wave energy advocates argue that the industry is where wind was 20 years ago. “Wave energy is not an ‘if,’ but a ‘when,’” says Justin Klure of the Portland-based consulting firm Pacific Energy Ventures. “There’s too much potential energy out there that we need to learn how to harness.”

And a growing number of companies are willing to brave these uncharted waters in the hopes of cashing in on those waves. “The wave energy industry is still so nascent, there is no way to tell winners or losers at this point,” according to Chandra Brown, vice president of Oregon Iron Works, the Clackamas-based company building the first Ocean Power Technologies buoy. She contends that Oregon Iron Works is technology-neutral; it’s eagerly watching to see how the field unfolds. “Right now there are probably 20 viable companies and designs out there, but the industry is still ramping up,” she adds.

Though one goal of the ocean planning effort may be to have the debate over fish or power up-front this time (as opposed to how it played out with hydroelectric dams), the precedent-setting agreements forged in Oregon between the feds, the state, one company, and the myriad interest groups are merely step one. Wave energy comes on the heels of five years of contentious debate over creating marine reserves. At a July 19 meeting of the Ocean Policy Advisory Council in Salem, the frayed nerves of those involved in the planning process so far were on view. “So much is going on so quickly that my coastal residents are tired, frightened, and mad,” said Betsy Johnson, a Democrat from Scappoose and one of nine state senators who form the Coastal Caucus. (Her district includes Clatsop and Tillamook counties on the north coast.)

Husing uses the phrase “coastal fatigue” to describe the burnout concerned participants increasingly feel. Some put it more bluntly. “I represent coastal people, and I don’t even want to go to another meeting,” said Lincoln County Commissioner Terry Thompson, half-jokingly—and the real work won’t begin until Ecotrust hands over maps based on the data this fall.

Attendees also received the expected news that the level of planning will only get more intense in months to come: on the same morning of that July meeting, the Obama administration unveiled the new National Ocean Council to jump-start efforts to develop marine spatial plans in the waters entirely controlled by the federal government, which start three nautical miles offshore.

Restless and vocal, Thompson showed his agitation. “Anytime I see the word ‘coordinate’ used in federal documents,” he churned, “I know it means, ‘Give us your information so we can tell you how to run the ocean.’”

Yet, as uneasy as fishers are, most are invested in the process—happier to have a front-row seat rather than trying to catch a glimpse from the outside. As Husing points out, fishermen spend the most time on the water. Now they have a way to share valuable information policy makers need.

Walking along the dock of the Newport fleet, Bob Eder furrows his brow as he shares his hopes and concerns. The biggest fear among him and his colleagues is that the data they are handing over could, one day, open the door to other industrial uses—for instance, to commercial-scale aquaculture or undersea mining—or that it could be used to further restrict fishing.

If only all extractive industries could be as sustainable as Oregon’s crab fishery has become, laments Eder. That’s one reason he is cautiously optimistic that, if the planning process is deliberate and maintains respect for biological resources, wave energy could be a sustainable ocean use. “One of the reasons fishing has survived,” he says as he looks out over the dozens of family-owned boats docked nearby, “is because we don’t own the space—the public owns it.”

(Oregon, according to Ocean Power Technologies’ Robert Lurie, enjoys the best conditions for wave energy generation of any place in the continental United States: Our coast’s waves are tall, frequent, and consistent. Transmission lines run along the entire coast. And no significant physical barriers (like major mountain ranges) stand between the buoys and the largest population centers. OPT’s first buoy, manufactured by Oregon Iron Works, will be deployed this spring. If it works as planned, its peak generation will be 150 kilowatts.)