Cycling Mosier's Twin Tunnels

First viewpoint headed west from the Mark O. Hatfield Trailhead, about two miles east of Mosier.

Image: Regina Winkle-Bryan

What a difference clear skies make on the Historic Columbia River Highway Trail. When I first biked this trail a few weeks ago, as one of 322 cyclists in the 10th annual Gorge Ride—a 40-mile derrière-bruising trek that starts in the Dalles—torrential rain, wind, and a burning sensation in my quads kept me from paying too much attention to the nuances of the landscape.

But today is different. I’ve put just nine miles of trail in front of me, not 40. No one is watching the clock, nor are there packs of competitive racers on $3,000 Pinarellos to remind me how slow I’m moving. This part of the trail is blessedly car-free. And perhaps best of all, the sun is out. It’s just me, Bluebell (that’s my bike—a $150 hybrid Raleigh from Craigslist), and a handful of midweek day-trippers.

Headed west from the Mark O. Hatfield East Trailhead, it’s uphill for a half-mile, which gets the blood flowing but is gradual enough to handle without too much downshifting. On Bluebell I ascend, approaching a family walking with toddlers and buggies. (Because the entire length of the trail is paved, it’s popular with the stroller crowd, cyclists, those in wheelchairs, and anyone else who needs a smooth route.) I'm relieved when I pass them—because even on a hill, it’s embarrassing not to pedal faster than walkers.

Soon I’ve reached the first viewpoint. The walls of the Gorge plunge below me into the fat blue snake belly that is the Columbia River. On the Washington side, the small harbor of Bingen clings to the banks; Chicken Charlie’s Island, with its lonely dock and mysterious structure, sits almost directly below me. The breeze zips through the dry canyon in big, warm pushes, and I’m certain the windsurfers are delighted. They hop across the cresting river in graceful bumps, like rocks being skipped by some unseen hand.

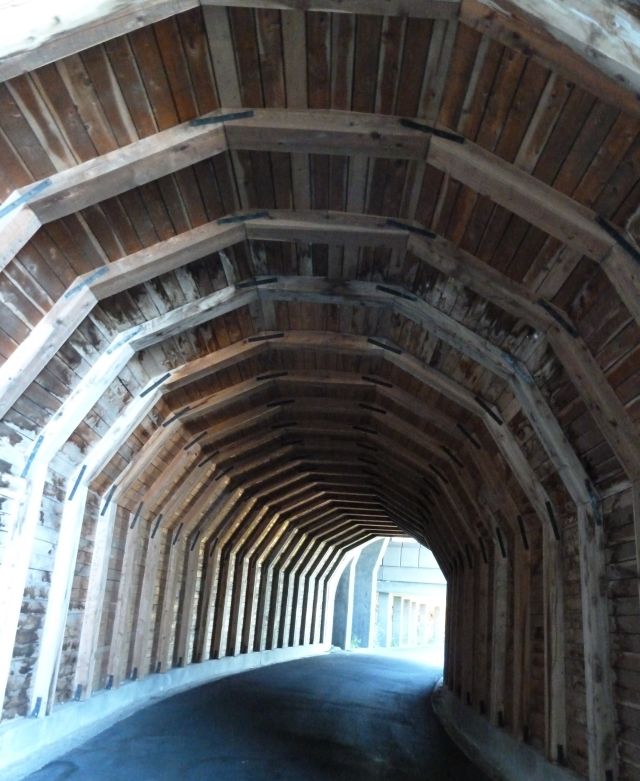

Now I'm coasting downhill into the mouth of the Mosier Twin Tunnels—the main draw for this section of the historic highway. Constructed a century ago, the tunnels span a total of 369 feet and offer a cool respite from the midday sun. Narrow, with adits punched through the cliffside to provide natural light, it’s easy to imagine Model-Ts puttering through here, as they did back when the scenic roadway was unveiled. Closed in the 1950s, the highway's tunnels eventually filled with rubble—impassable until cleared, revived, and reopened in 2000 as a designated national historic landmark.

The twin tunnels are practically connected—you might not realize they're two distinct structures. This, the second, is timber-lined and gently curved.

Image: Regina Winkle-Bryan

Once through the tunnels, it’s more uphill, so I flip Bluebell’s kickstand for a water break. Cyclists hurtle past in skin-gripping ensembles, blurs of neon, sweat, and carbon frames. They are dressed for a longer ride and will probably keep pedaling beyond this car-free leg and on into Hood River via curvy Highway 30. (Everyone was dressed this way on the Gorge Ride—my first indication that I was way out of my league. While I tightened the laces on old running shoes, sporting loaner padded shorts, two sizes too big, these pros tapped up to the starting line with clip-ins and snug waterproof windbreakers.)

Today I am wearing those same shorts and a yoga tank top. I’ve got some water, a bit of tuna jerky, a banana, and my camera. One doesn’t need much more than this for this stretch of the trail—it’s a gentle affair that forgives ill-preparedness.

The Mosier Twin Tunnels leg of the HCRHT passes through both high desert landscapes and lush forests: here, I passed through a dappled grove of Oregon white oak and big leaf maple.

Image: Regina Winkle-Bryan

Moving on from my break, I enter a shady section of trail lined on both sides by Oregon white oak, bigleaf maple, and ponderosa pine. Cicadas and birds sing up in the branches. I stop near a clump of ferns to photograph the idyllic surroundings, and that’s when I hear a snapping and rustling in the brush 50 feet away. A gray squirrel? The crunching intensifies and suddenly I’m frightened. I jump on Bluebell and hit it hard, telling myself that it was probably a whitetail deer.

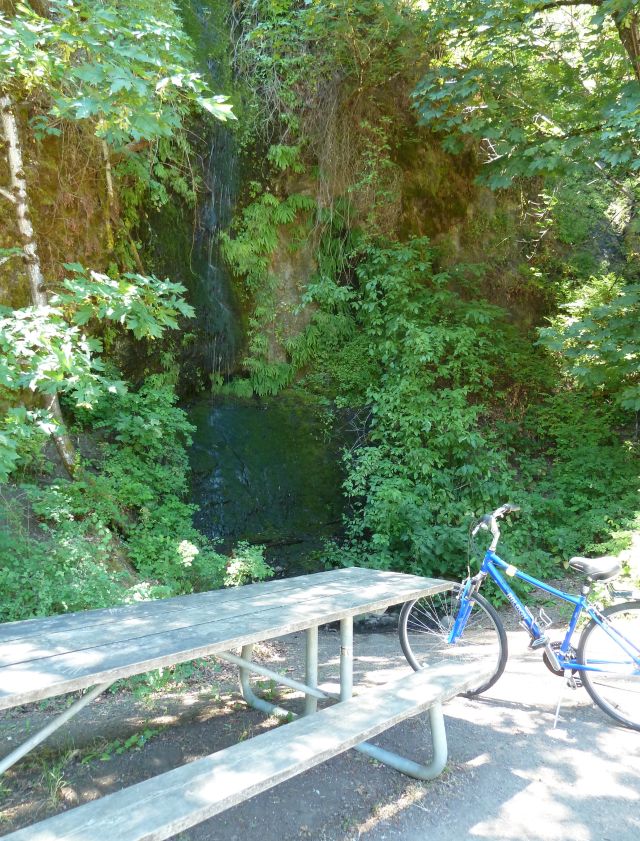

A picnic table hugs a high cliff just feet from a small, cooling cascade—the only water (beyond the mighty Columbia) that I saw in my late June foray.

Image: Regina Winkle-Bryan

I slow my pace and notice the blackberries, chubby indigo clusters, ready to be picked, but I don’t stop for them. On the right, Mount Adams peeks out like a sparkling opal between brown foothills. After a bit more up, up, up, the sound of splashing reaches me and the scent of water fills the air. A delicate cascade comes into view, dripping from a basalt overhang and filtering through fibers of green moss. There’s a table next to the waterfall, the best spot on the trail for a picnic.

It’s not much further to the end of the trail and the visitor’s center, which is open. I pop in and chat with a friendly volunteer who lives in an RV behind the center.

“Just a couple days ago a hiker came across a mother bear and two cubs,” he tells me.

“Where?”

“About a mile back down the trail.”

I calculate where I had heard the rustling and tell him about it.

“Might have been a bear,” he shrugs, “but they’re just black bears; not going to bother you.”

Just in case, I eat all my tuna jerky before setting out on my return leg. I’m pedaling a little harder on the return and I don’t take breaks. If nothing else, that bear could hear me coming—and I certainly earned my supper!