Will Trump Ransack Oregon's Public Lands?

On the morning of July 15, 2017, a tall Montanan in a cornflower blue button-down hiked a beautiful two-mile spur of the Pacific Crest Trail.

“Hi, I’m Ryan,” the strapping rambler greeted those he passed: a nature photographer, a watercolorist set up by a ridgeline meadow, a queue of birders. He gave a chestnut horse a clumsy pat; he startled some PCT thru-hikers. In fairness, he did cut an unusual figure. Behind him trailed a clutch of uniformed Bureau of Land Management officials, a camera operator, and a Wall Street Journal reporter documenting his every move.

Ryan Zinke, the Secretary of the Interior, wanted a firsthand look at Oregon’s Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument: an area of about 170 square miles (a little bigger than Portland city limits) that straddles the California border just east of I-5. On maps, the monument looks like a rabbit resting on its haunches, “ears” antennaed east toward Klamath Falls and west to nearly graze Ashland.

“Beautiful country,” the secretary opined that afternoon at a press conference at nearby Hyatt Lake. “People are incredibly passionate about this monument. I haven’t seen anybody that doesn’t want to protect this.”

He then turned and opened his arms to sweep in a mix of public and private land that, according to a 1995 BLM report, hosts “perhaps the greatest biodiversity of any area in the state of Oregon.” Biodiversity came up a lot that day and the next, as Zinke made the rounds. Of the 150-some national monuments created by American presidents via Teddy Roosevelt’s 1906 Antiquities Act, only Oregon’s Cascade-Siskiyou has, as its “object,” the protection of many habitats instead of a singular feature. Bill Clinton, who designated the monument in 2000, called the area “spectacular.” Barack Obama, expanding Cascade-Siskiyou just days before Donald Trump’s inauguration, acclaimed its “ecological wonders.”

Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke

Now Zinke, a burly ex-Navy SEAL who last year ascended to Trump’s cabinet after a brief stint as Montana’s lone House rep, arrived in the midst of a blitz review of 27 monuments created or expanded since 1996. “Our public lands belong to all of us,” Zinke told reporters. “Going forward, the biodiversity can and should be done incorporating traditional use.”

As a new Montana state senator in 2009, Zinke was known as a Prius-driving “Green Republican”—or, as he put it, a “Teddy Roosevelt Republican.” But over the course of his 10-year political career, he’s increasingly favored extractive industries, grazing, and motorized recreation over conservation and environmental regulation. (“Traditional use” is a term of political art for the former priorities.) As a congressman, Zinke waffled—hard—on climate change. By 2017, the new Interior Secretary vowed that the nation’s vast public lands would help make America “energy dominant.”

Five weeks after his Oregon visit, Zinke reported back to his boss. His memo, promptly leaked, urged Trump to shrink four of the monuments under review, invoking “traditional use” 22 times over its 20 pages.

Cascade-Siskiyou is on Zinke’s shortlist for reduction. Already, Trump seems to agree with his secretary. In December 2017, the president slashed back Utah’s Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears—by 50 and 85 percent, respectively. Coal, oil, and gas leases, fast-tracked by Zinke’s BLM, now proliferate within their rescinded boundaries—as do federal lawsuits filed by Utah tribes, conservationists, and outdoor retailers like Patagonia.

Oregon is a different story. If Trump turns to the swatch of Southern Oregon where “Ryan” went hiking last July, then yes, we’ll be the next flash point of debate. But Oregon’s public lands are in legal limbo regardless, thanks to another issue that entangles Cascade-Siskiyou.

It’s not going to be pretty. Now, more than ever, the American West is in conflict with itself, a battle between our powerful interest in exploiting natural resources and the potent urge to protect our defining landscapes. In Oregon, we’ve heard this debate before, from signature conservation achievements to the Malheur occupation by insurgent ranchers. Maybe the real question is, who wins a debate when neither side is listening?

On the way to Hobart Bluff, lichenologist John Villella bounds through late-spring snowpack to a dwarf white oak just off the Pacific Crest Trail. He wants to show off the fluff that covers its still-bare branches: hair lichen, bone lichen, wolf lichen, spongy fungi that range in color from gunmetal gray to fluorescent green.

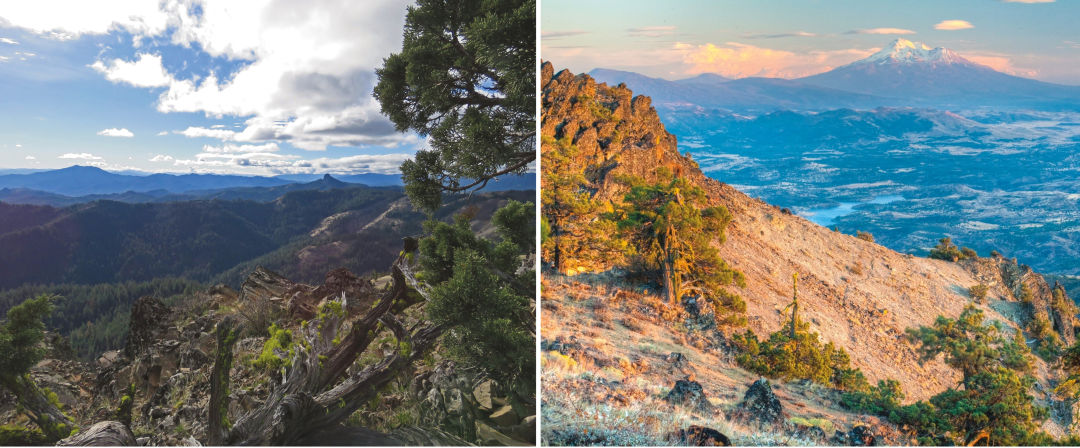

“These are species you’d commonly find in very different climates,” he says, listing impressive medicinal uses for what looks, let’s be frank, like mattress stuffing. But his excitement is infectious; by the time we reach a meadow overlooking the Cascade-Siskiyou’s Soda Mountain Wilderness, we’re both eagerly inspecting rock buckwheat and just-flowering saxifrage, marveling at a gnarled incense cedar, and bemoaning the lack of native bunchgrass, crowded out by invasive grasses dispersed by grazing.

From the summit, everything we see, Villella says, is prime territory for the first gray wolf known to western Oregon since 1947—OR-7, a.ka. Journey. Here, too, roam bobcats and black bears, great gray owls and rare butterflies, charismatic Pacific fishers, and the adorable, conversational pika, a snub-eared cousin of the rabbit that eeps in multiple “dialects.”

This abundance—everything from apex predators to humble lichen—speaks to the distinct topography of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. Four ecoregions overlap here, where the Cascade Range slopes toward the Siskiyous to form a high-elevation land bridge connecting alpine meadows and old growth, scrubby chaparral and sprawling “basin and range.” The area is a passageway for species seeking food, love, or better luck; it’s where you cross over if you’re an elk, an owl, or, 150 years ago, a fortune-seeker on the Applegate Trail, traveling by caravan to the gold mines of Jacksonville.

The day after Zinke’s hike last summer, Oregon Gov. Kate Brown was here on horseback. Brown, an avid equestrian (and urban liberal Democrat—the conservationist to Zinke’s cattleman), rode through nearby backcountry amid flurries of butterflies. An ardent supporter of the monument, Brown reportedly offered to host Zinke’s visit and was rebuffed. (Zinke favored the hospitality of Republican Greg Walden, of Oregon’s sprawling Second Congressional District, covering most of the eastern and southern reaches of the state.) Brown settled for an hour-long meeting with Zinke at the BLM’s Medford headquarters. Then, she held her own press conference.

“We like to make decisions in Oregon based on science,” Brown said, pointedly. “I urged him not to turn their back on progress that we’ve already made.”

Brown’s guide for her trip was Dave Willis, a Corvallis-raised conservationist who learned to love the outdoors as a climb guide for church and school tours. In 1979, he moved to Jackson County, exploring every inch of the Soda Mountain outback by horse after a climb on Denali cost him fingers and most of his feet.

Willis, by many accounts, is the man behind the monument. In 1984, he began advocating for the Soda Mountain Wilderness Council. Through the ’80s, he and a team of experts—ornithologists, climatologists, terrestrial ecologists—studied the area before pushing the BLM to recommend the wilderness area to Congress in 1991. In 2000, Willis and allies urged the Clinton administration to create the national monument; between 2011 and 2016, he helped argue the case to Obama for doubling the monument’s size.

Villella is on Willis’s team: a consultant commissioned by the BLM to inventory rare plants and catalog grazing impacts.

“During those first years, I just noticed all these butterflies,” Villella remembers. He’d stop constantly to snap photos. Eventually, he says, “I had to limit myself to one picture of a new butterfly a day, during my lunch break.” Last year, an artist painted 40 of the photos—just a third of the species documented within the monument—into a poster. His current favorite is the Klamath mardon skipper—extremely rare, Villella says, imperiled, and unconventionally beautiful.

Views from within the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument, where the intersection of several distinct ecological regions produces one of the state’s most biodiverse landscapes

Some 30 minutes east of Ashland, down the wicked curves of State Highway 66, the Green Springs Inn’s old-timey rotating case displays butter-crust cream pies, nut pies, and fruit pies. (The inn also serves Arch Rock beer on draft, local grass-fed-beef burgers, and scratch-made cinnamon rolls as big as your face.) Then there’s the location. The restaurant, the motel behind it, and the nine luxury vacation cabins in the pines farther back are all folded deep within the Cascade-Siskiyou—one of many private “inholdings” grandfathered into the monument under Clinton’s 2000 proclamation. Since then, some owners have sold to the BLM; others have stayed on, enjoying living within a special place—and the economic benefits that come with that.

“It was limping along when we bought it,” says Diarmuid McGuire, who took over the inn in 1994, moving into the apartment upstairs with his wife and four kids. “The magic really started happening in the early 2000s.”

To McGuire, the monument made sense: timber and grazing were the old economics, while the future looked more like tourists, hikers, wedding groups, and scientists like Villella. (Villella’s butterfly poster hangs, framed, across from the pie case.) McGuire’s wife, Pam Marsh, carried that message into local politics. While serving on Ashland’s city council, Marsh traveled to Washington with Dave Willis to lobby for the monument expansion. Now a state legislator, Marsh stood next to Governor Brown during her July 16 press conference. To them (and to others), tourism—and destinations like the Green Springs Inn—offer more economic upside than logging high-elevation forest like this, anyway.

“Trees don’t grow fast enough for Wall Street around here,” McGuire says. “Sorry, but those days are gone.”

McGuire and Marsh often represented that posture at the many public meetings that preceded the 2017 expansion. Countering the arguments of these conservationists: county commissioners, cattlemen, timber interests, off-road enthusiasts. Willis attended, too. What Willis heard from the “No Monument” crowd, he says, mostly boiled down to “people who don’t like the Antiquities Act, people who don’t want the president to tell them what to do.” Willis has little patience for those who argue that the monument limits public access. There are still plenty of roads, he says—412 miles in the original monument—but that’s missing the main point.

“It’s a simple proclamation: it’s to protect the objects,” he says, referring to Clinton’s 2000 designation. No matter how opponents want to spin it, Willis says, “human enjoyment isn’t the purpose of the Antiquities Act.”

In a climate where even science is considered partisan, supporters of the Cascade-Siskiyou expansion are stockpiling legal options. They’re counting on powerful partners—Brown and her attorney general, Ellen Rosenblum—to blunt any federal efforts to shrink the monument. Rosenblum says she’ll bring the Antiquities Act to court—in a first for a US state—if Trump even nicks it. The act, she asserts in a July 10, 2017, letter to Zinke, is “a one-way mechanism for protection and conservation.”

If Brown and Rosenblum represent the tip of the spear, the throwing arm is their electorate: those left-leaning Oregonians who want their public lands statuesquely unlogged. The state officials represent this view of Oregon’s future—one that largely rejects Zinke’s allegiance to an industrialized rural West.

Ryan Zinke, like his boss, tends to speak off the cuff, with great confidence, if not always great words. (He once greeted Hawaiian congresswoman Colleen Hanabusa with a hearty “Oh, konnichiwa!”) His tenure as Interior Secretary has been bumpy. He’s been repeatedly mocked by the media—for riding a horse to his first day on the job, for installing a $139,000 fiberglass door to his office, for rigging his fly-fishing rod backwards during a field interview, and for dusting off the Interior Secretary’s personal flag (last used—well, no one remembers) and insisting it fly whenever he’s in the agency’s DC headquarters. A buddy from Whitefish somehow ended up (briefly) with a contract to restore power to post-hurricane Puerto Rico. During the reporting for this article, the press nailed Zinke’s habit of describing himself as a “geologist”—he has a University of Oregon bachelor’s in that field but has never held a geology-related job.

For all the bumbling about, the Bozeman native has shown laser focus, and progress (if you will), on one goal: expanding industry’s reach on public lands. During his July visit to Oregon, Zinke and Walden attended a fundraising dinner at the swanky Jacksonville Inn, which included prominent area ranchers. “He wanted to know what we wanted from him,” one of the Oregonians told the Malheur Enterprise. “It was good to meet the man and get our foot in the door.”

A long night with industry interests reflects Zinke’s usual allocation of time. “We know how much time he spent with the monument’s opponents,” says Willis, ticking off meetings with snowmobilers and ranchers. Zinke attended a timber sale; he met with anti-monument county commissioners. Aside from the hour-long meeting with Brown, monument supporters were allocated just 30 minutes on the secretary’s schedule, at the tail end of his two-day trip. Willis had convened 17 leaders, including the mayors of Ashland and Talent. Each had just 45 seconds to speak—which was tricky, Willis said, as the secretary kept interrupting.

Beautiful (and, yes, biodiverse) as it is, Cascade-Siskiyou is small. But the politics of its potential contraction could reverberate throughout the state—specifically, on about 2.5 million acres of mostly coastal forest.

This goes back a bit: in 1866, Congress gave the Oregon & California Railroad a bunch of land. The railroad never took off, and in 1919, the land reverted to public ownership. In 1937, legislation gave the counties with so-called “O&C lands” the right to trade its timber for cash. Within Obama’s expansion of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument, some 16,500 acres are prime O&C harvest lands. The monument designation takes those acres off the market. Greg Walden wants them logged. He certainly seems to have convinced Zinke.

“I appreciate all the time Rep. Walden and local stakeholders spent with me in Oregon,” the secretary says in a December 2017 press release timed with his official monument recommendations to the president. “I heard from locals that we need to conserve the land, care for the forest, respect private property rights, and allow for sustainable timber harvests in O&C lands.”

Shortly after Obama’s proclamation, timber interests filed lawsuits, claiming a pre-existing right to log ex-railroad land now inside the monument. Murphy Timber Co and others argue the 1937 O&C law mandates “permanent forest production,” overruling both Obama and the law that authorizes national monuments.

The defendant in these suits is the BLM itself. Environmentalists doubt the Trump administration will fight to protect an Obama proclamation, so they’ve entered the fray themselves. In February of this year, the influential Portland-based nonprofit Oregon Wild, among other groups, filed separate motions to intervene on the BLM’s behalf. In June 2017, a federal judge delayed one case while Zinke conducted his review. In April of this year, the case resumed, with administration filings that environmentalists found tepid indeed.

For Steve Pedery, Oregon Wild’s conservation director, the stakes in the O&C-related cases run high. “It sounds like a byzantine debate,” says Pedery. In his view, the timber company’s lawsuit isn’t really about the meager timber in this monument—it’s a struggle for control over all of Oregon’s O&C lands, including millions of acres of rich coastal timberland further west.

“It’s really about whether we’re going to log these last, low-elevation old-growth forests,” he says. In a larger sense, the legal and political maneuvers around Cascade-Siskiyou are about which America wins: one dominated by “traditional use,” or one that steps back, setting aside big wild places for future generations.

“People sometimes describe it as a culture war, and I think that’s somewhat accurate,” says Pedery. “It’s this debate over the future of the West.”

At the Green Springs Inn, Diarmuid McGuire is getting ready for summer traffic; this season, he’s counting on summer interns from Southern Oregon University to staff the BLM’s makeshift monument welcome center next to his restaurant. In front, McGuire has planted a simple black-and-white “Yes, Monument” sign. It directly faces his neighbors, across the road, and their own sign: “No Siskiyou Monument Without A Vote: Access to Public Lands.”

McGuire says they’re still friends, as long as they don’t talk about the monument.

Editor's note: an earlier version of this story misidentified the area within the monument where Gov. Kate Brown rode on July 16; she toured the Little Hyatt Old-Growth Groves, not Hobart Bluff.