How Women on Bikes Have Raised Hell Throughout History

Ginny Wood and Celia Hunter cycle touring in Europe in 1948

Image: Courtesy Tessa Hulls

For a brief spell around the turn of the 20th century, the bicycle was the hottest vehicle around. Starting in the mid-1880s, as the first bikes with equally sized wheels (oh, the innovation!) hit the cobblestones—and weren't yet competing with cars—these miracle machines offered new opportunities for freedom and independence. They also became tools for defying convention and pushing for social change.

Tessa Hulls

Image: Courtesy Tessa Hulls

That’s the argument Tessa Hulls brought to Portland on Tuesday, March 26. Hulls, a visual artist, writer, and researcher based in Port Townsend, Wa., has over the last year developed an impressive side hustle as a feminist adventure historian. “It’s something that grew out of my personal experiences as someone who does a lot of wilderness travel solo and was told all the time that women can’t do these sorts of things alone,” says Hulls, who took a 5,000-mile solo ride from southern California to Maine in 2011 and has since pedaled around Ghana, Mexico, Cuba, and Alaska. “It began as a line of research inquiry that accidentally morphed into my profession.”

For her presentation, which she calls "Women, Trans, and Femme Riders in Early Cycling History,” Hulls mined primary-source documents to consider the bicycle fever of the late 19th century through a lens of gender and civil rights. “I look at how bicycles affected things like gender equity and racial representation,” she says. “It’s equal parts history lesson and storytelling about female-identified people who were able to do really incredible things.”

Billie Samuels, an Australian endurance racer, setting out for a 1,000-mile ride from Melbourne to Sydney in 1934

Image: Courtesy Tessa Hulls

To that end, expect no shortage of badass accomplishments, from stunt cyclists of yore to 14,000-mile trips across India. But Hulls—who became a bike commuter in Portland, while studying studio art at Reed College—is interested in more than just what these women did on two wheels. “The fact that these women ride bikes is not what’s so interesting about them,” she says. “It’s what they used the freedom that they found through cycling to do with the rest of their lives, and how they advocated for social change.”

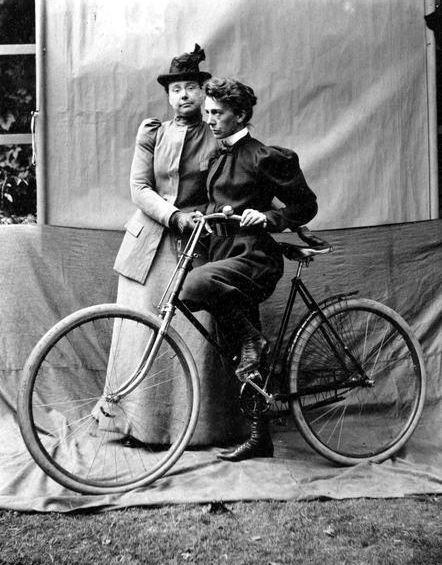

Hulls mentions environmental activist Ginny Wood, born in 1917 in Moro, Oregon, just south of Wasco. Wood took several bicycle tours through Europe—one in 1938, as the continent was on the brink of war, and again a decade later, amid the rubble (see top photo)—before settling in Alaska, where she helped build Camp Denali and co-founded the Alaska Conservation Society. She also steered winged vehicles: she served with the Women Airforce Service Pilots, flying military aircraft during World War II.

Behind the scenes at a photo shoot for Marie E. Ward's Common Sense of Bicycling: Bicycling for Ladies, 1886

Image: Courtesy Tessa Hulls

Or take Fanny Bullock Workman, who paired her wilderness exploits—numerous mountaineering expeditions in the Himalayas, as well as that monster tour through India, which began in November 1897 and ended two and a half years later—with advocacy for gender equity and women’s suffrage. (Both Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton also extolled the liberating potential of the bicycle, connecting it to the fight for the vote.)

In addition to stories, Hulls has collected hundreds of images for an accompanying slide show, from century-old photos to newspaper clippings. For her part, Hulls is particularly fond of the comics she dug up, which tend to suggest that bicycles will turn women into uncontrollable hellions. “The status quo was flipping their shit over women exploring this newfound freedom,” she says. “If a woman gets onto a bike, she’s going to become this aggressively masculine, chain-smoking, no shits-given terror. What will happen to a proper lady if she mounts a bicycle?! I just appreciate those.”