Carson Ellis Finds Her Past in an Old Portland Warehouse

The artist Carson Ellis broke into a Southeast Portland warehouse on a recent afternoon. “I snuck in with my kid,” she told me. “He was not stoked.” Milo, her 11-year-old, asked if they were trespassing. Ellis supposed they were. But she had at least a half-defensible reason to be there. This former chicken slaughterhouse, the Oak Street Building, was her first Portland home. If you’ve ever visited a place you once lived, you’ll know the feeling: it beckons—as if the door is a portal to the time you lived there. For Ellis, this door led to January 6, 2001, the first day she woke up in the apartment/art studio she kept in the warehouse for a few years. In many ways, it wound up being the first day of the rest of her life.

Her “carefully stoic” diary of the time, what she now calls a “found text,” guides her new book, One Week in January, out September 10. The entries, scented with cheap cabernet and Heineken, cigarettes and mooched pepperoni pizza, sit alongside new paintings Ellis made after finding the diary in storage. A swirling air of self-creation hangs above: we see her reading Dylan Thomas aloud to herself, and of course we only see this because she wrote about it in her diary. Ellis, now 48, sees this 25-year-old version of herself almost as a different person. She paints her younger self with the artistic voice she’s honed in the intervening decades, and with a moving tenderness and gentle retrospect, she transcribes, translates, illustrates her past self’s over-earnest and somewhat romanticized squalor. “[H]er life is brimming with possibility,” Ellis writes in the forward. “Sometimes she even knows it.”

Ellis has since become a bestselling children’s book author and revered illustrator. Her books, like Du Iz Tak?, often assume made-up languages and tend to read more like “an incantation than a story,” per a New York Times review of her 2020 Caldecott Honor book In the Half Room. Pick a magazine or newspaper and Ellis has likely painted or drawn something for them. She’s also a prolific illustrator of other author’s books, everyone from Lemony Snicket to the guy who lived in the apartment below hers in that warehouse, Colin Meloy.

Reading through One Week in January, it’s apparent that being close to Meloy was a big part of what brought Ellis to Portland. They were college friends. She was in love with him; he was in love with his guitar and devoted to writing what would become the first Decemberists record. Her apartment wasn’t really an apartment. It was illegal to live in the building, but it seems everyone did. The bathroom was in the hall, and Ellis used the kitchen, computer, TV, and VCR at Meloy’s—the cigarettes and wine too. Eventually, they married, had two kids, and produced, among many other projects, the Wildwood Chronicles together, a children’s fantasy trilogy Meloy penned and Ellis illustrated.

At times to a comic degree, the diary is written as if it hopes to be found by someone in the future, as if the people it involved were destined to become somebody. And a lot of them were. Outside of Ellis and Meloy, Marriage Records, the local label that put out early Tune-Yards and Dirty Projectors albums, had an office there. The Pitchfork critic Julianne Escobedo Shepherd did too, writing about music for the Portland Mercury at the time. The gallerist that Ellis still shows with, and with whom she’s showing the paintings from this book (September 14–October 19 at Nationale), May Barruel, ran an early iteration of what would become her gallery Nationale in one of the warehouse’s units.

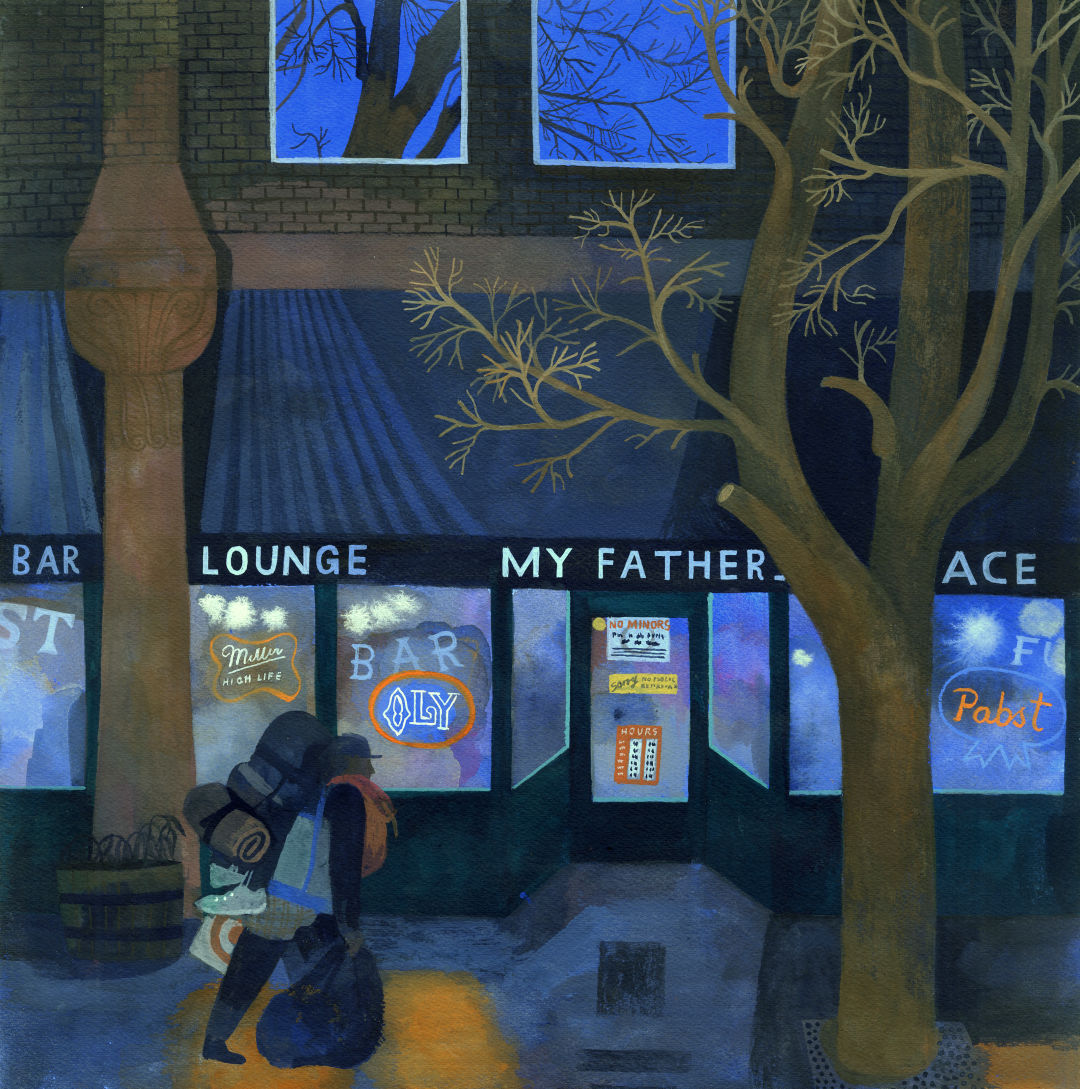

But Ellis knew better than to record any of this in the diary. Instead, she tried her best to maintain a cooly disinterested tone, not ready to admit, or maybe not fully aware, that she saw the moment as the precipice of something. There are hints, though. Most telling, perhaps, are the instances where she writes about writing the diary, in the diary—“wrote down the day before.” Or later, when she writes about Meloy reading it aloud to a group of friends, not as a betrayal but as a joke they all seem to have been in on, poking fun at her navel-gazing but listening intently all the same. It was one of many art projects her cohort informally workshopped, like her paintings, friends’ short films, and Meloy’s songs. Together, they laugh about how dull it was: Ellis depositing a Hanukkah check her uncle sent or eating cereal and bananas for breakfast; trips to Dots, Portland Meadows, and My Father’s Place where they do their best to fit intellectual references into casual conversation. In a way, the diary was a means by which to workshop her own identity. “It’s not impossible,” Ellis joked to me, “that I read Under Milk Wood one and a half times to myself before bed so I could write about it.”

It’s not just Ellis’s future success that makes this week in the life of a young artist trying to find herself interesting. The book isn’t a memoir tracing back the moves that shaped her into a celebrated artist. Nor is it merely a scrapbook of memories. Notably, One Week in January is the first book Ellis has written for adults. And aside from including cigarettes and booze, she says the change in audience freed her to let the paintings, rather than the words, drive the project. It can function as an exhibition catalog accompanied by an experimental essay, with a narrative that may be, true to form, more of “an incantation than a story.” And what is it a spell for, what mood does it conjure? The messy riddle of self-creation that every artist undertakes.

Putting together the book today, Ellis says, felt more like putting pictures to someone else’s words than to her own, the dialectic of author and illustrator sizing each other up. This split creates a fascinating feedback loop: of an artist looking for their past self and finding the one they created all those years ago, a past self that no doubt longed for the approval of someone like the artist she turned out to be.

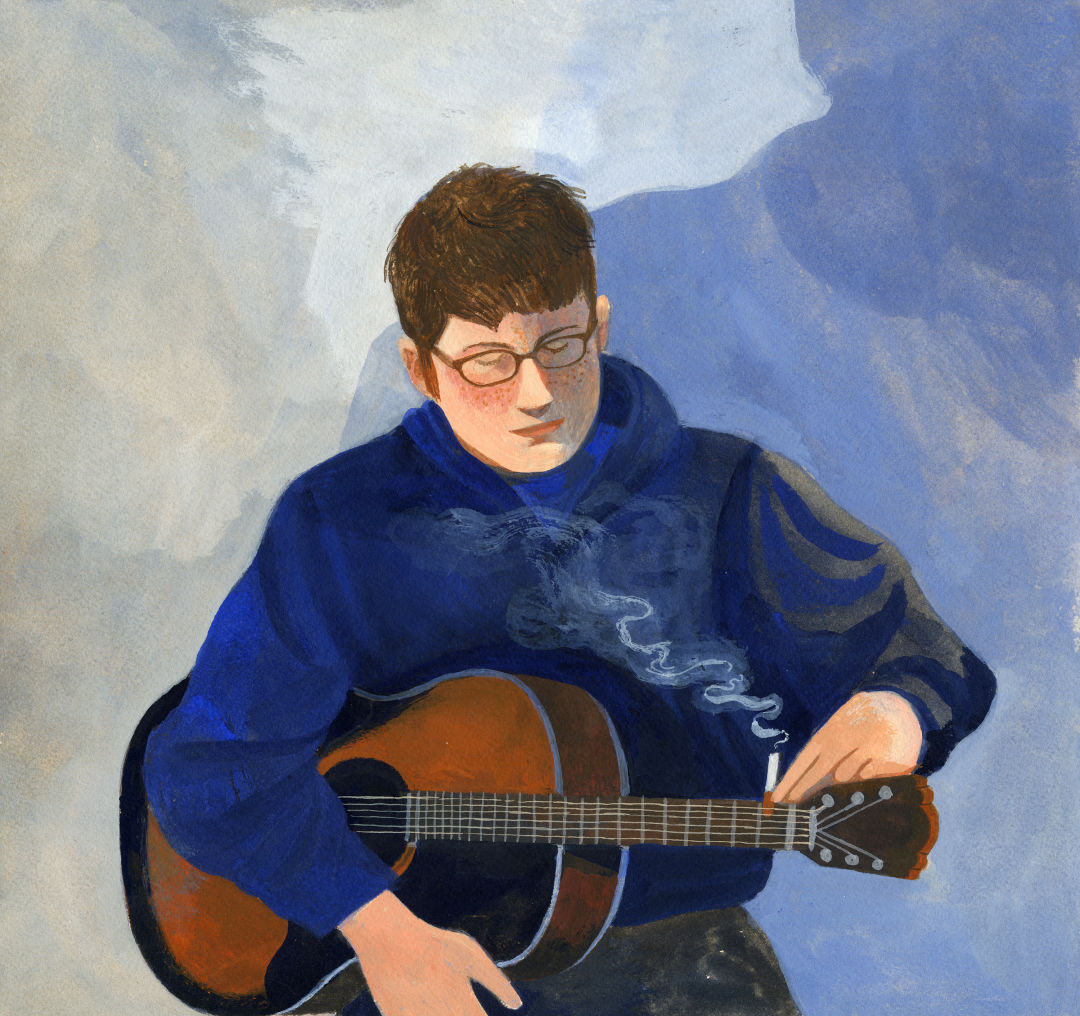

Largely, Ellis refuses to reconcile the two. While she usually finds painting self-portraits near impossible, painting her past self was easy enough. “I can kind of invent her,” she says, “as she was inventing herself.” Trying to paint Meloy, however—“there was something weirdly emotionally overwhelming about it,” she says. “If you spend 25 years looking at someone, you’re like, ‘What does that person even look like?’” Ultimately, she did muster a portrait of him. He’s pinching a cigarette between the strings of his sunburst acoustic guitar and wears a swoopy boyish haircut—very much an indie Portland 2001 heartthrob. She admits she couldn’t get the eyes quite right and wound up having to paint them closed.

The portrait of Meloy, and most of the paintings in the book, are based on old snapshots. But one scene came from a photo Ellis shot on her and Milo’s recent illicit visit to the warehouse. It’s of an enticingly cluttered corner, loaded with pipes, knobs, wires, chains, and a fire exit door. Standing there 20-some years after the fact, in the hallway she used to run through constantly—to use the phone, to check her Yahoo email, “to jump in bed with Colin if woken by a bad dream”—seems to have collapsed some of the divide between these split selves. In the painting, the shadow of a nondescript figure is cast against the wall. It’s subtle enough to miss at first glance, and recognizable only as the vague outline of a person. But that shadow might be a bridge. Maybe it’s a picture of past and present selves colliding.