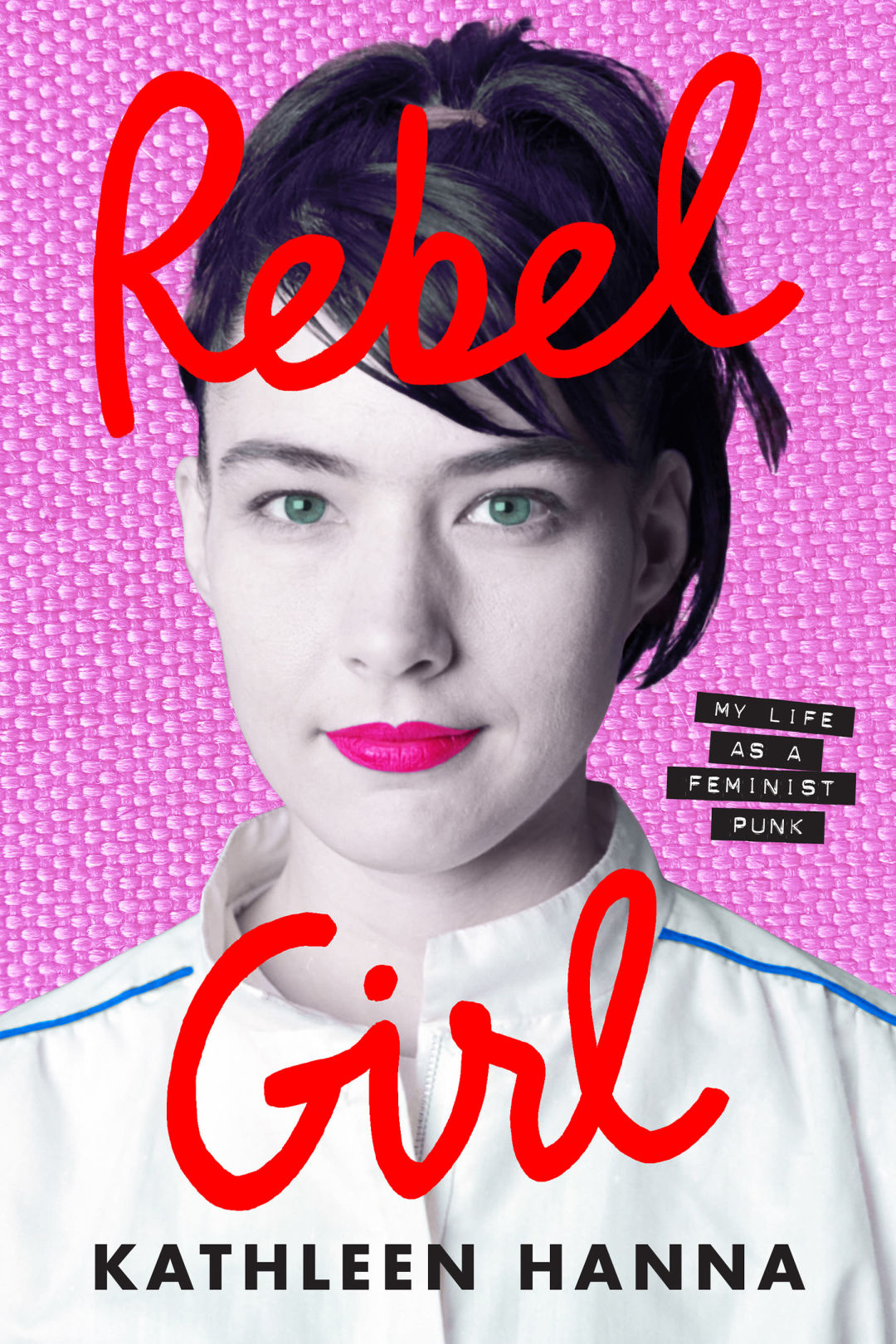

Riot Grrrl History in Kathleen Hanna’s Rebel Girl

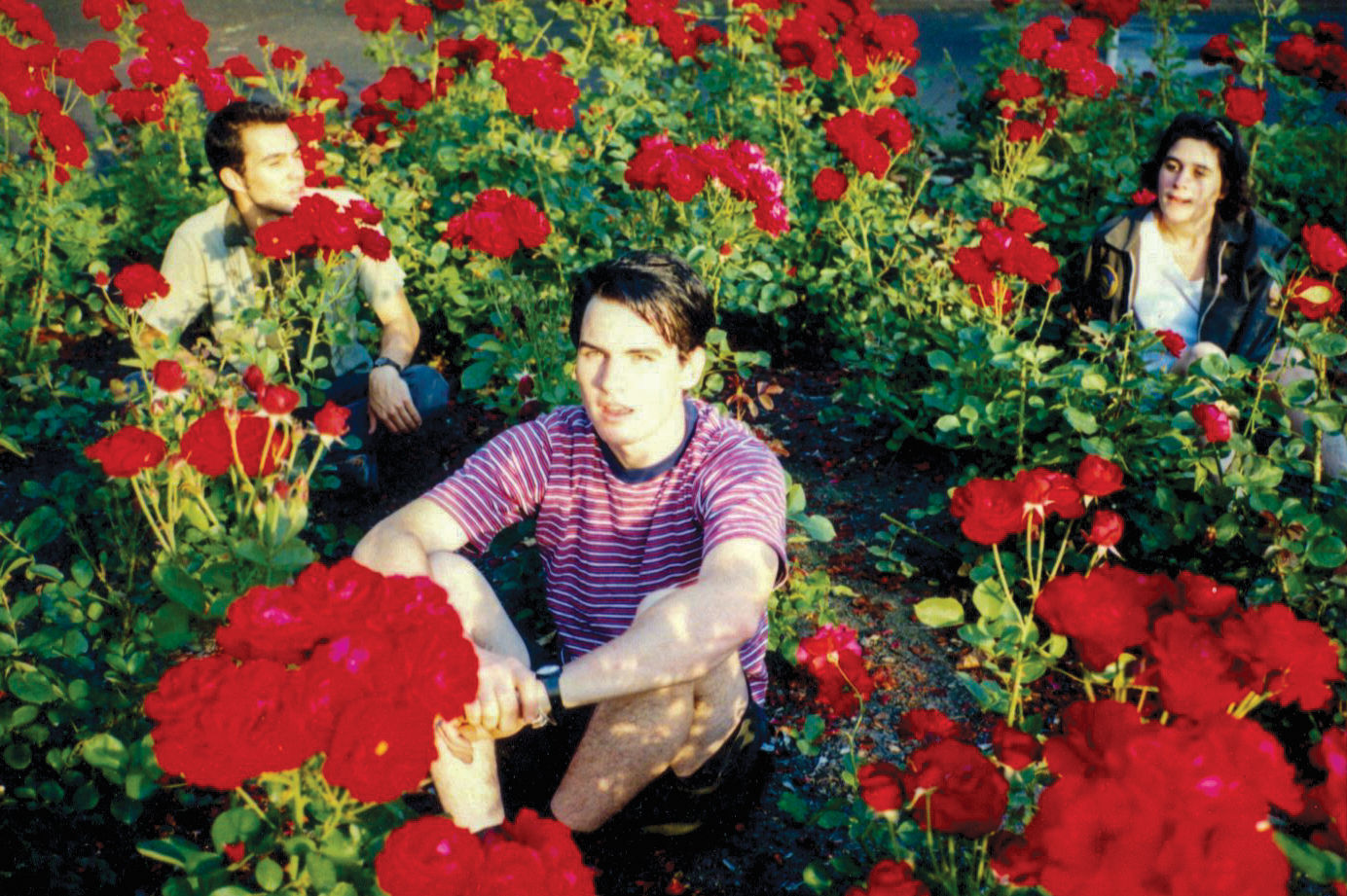

Image: Leeta Harding/Courtesy Ecco

We tend to romanticize the era and place that produced art we love, turn it into a fantasy fertile wonderland where people just wake up every day and make great music, start world-changing political movements with nothing but a Sharpie and a stapler, love and support each other, and never worry about money. This happens with Old Portland, of course, and it can be easy to do it with Olympia, Washington, in the late ’80s and early ’90s, now considered hallowed ground in many a riot grrrl retrospective and zine archive. But girl-style revolution, or any revolution, really, doesn’t happen because everything is fine and dandy. In Kathleen Hanna’s new memoir, Rebel Girl, Olympia is a place where it’s OK for an ex-boyfriend to turn his art show into revenge porn, where Hanna and friends start their own art gallery after a Boy Scouts leader ruins the prints she’d hung up in a hallway at the Evergreen State College, where her roommate is severely beaten, where Hanna is raped (not for the first time) and later stalked.

It is also a place, though, where a future punk superstar can be “discovered” simply by being seen writing in a journal at a café by K Records founder Slim Moon and invited to perform at a spoken-word night; where you can keep that art gallery/music venue afloat because your friend is friends with Kurt Cobain, whose band Nirvana, two years before Nevermind, could draw a good-sized crowd for a benefit show; and where Tobi Vail might pass up an invitation to play drums in Nirvana because this feminist project of yours sounds more fun.

Hanna’s book, subtitled My Life as a Feminist Punk, details how the wrongs add up, how they forge connections, how they get people talking to each other. A lot of Hanna’s punk-rock bio is the stuff of legend, attaching her to the pre–Spice Girls use of the phrase “girl power,” along with “girls to the front” and “revolution girl style now,” as well as the indirect naming of Nirvana’s hit “Smells like Teen Spirit.” (On a night of drunken shenanigans, she had scrawled “Kurt smells like Teen Spirit” above Cobain's bed, a reference to the then-new deodorant marketing to teenage girls, which had made her laugh when she saw it in the drugstore.) In Rebel Girl, which shares a title with the Bikini Kill song long since immortalized in Rock Band video games, countless covers, and karaoke nights, she connects the dots of how trauma and happenstance ended up giving shape to what would become a political and cultural movement and her own enduring music career.

Image: Rachel Bright

Born in Portland, Hanna spent her childhood in suburban Maryland with an unhinged abusive dad before the family moved back to Portland in time for her to attend Lincoln High School. There, she decodes the cliques and describes her classmates as “mostly rich kids who’d been friends since they were babies and had all done this thing called ‘dancing school’ at the nearby Multnomah Athletic Club.” The late Walter Cole, Hanna’s second cousin (who was also known as the drag queen and eponymous club owner Darcelle XV), makes a cameo in Rebel Girl as one of the first people to compliment her singing—a performance at her sister’s wedding. Hanna describes the validating as being “knighted by entertainment royalty.” Portland is linked to a few full-circle moments: from Hanna seeing the Go-Go’s at the Paramount Theatre (now called the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall) to Bikini Kill opening for them in San Francisco just over a decade later, from her frequenting Starry Night (now the Roseland) as a “drunk teenager” watching the Bangles to performing on that stage herself with her mother in the audience.

Much of the book is a tour diary from a time before the modern aids of cell phones, Instagram-fed publicity, and what she calls “wheelie luggage,” first with band Evil Knievel and later with Bikini Kill. Hanna would collect actual, physical addresses from concertgoers to send them zines or postcard announcements of future shows. Showing up to the concert with hearts and stars Sharpied on your hands meant you’d received a postcard and were part of a community.

Less nostalgic, perhaps, are the accounts of scraping together funds. Hanna worked at Mary’s Club in Portland to pay her tuition at Evergreen. Later, she took a job stripping in DC to pay for repairs to the tour van. “If you ever wonder why so many well-off kids were in nineties punk bands, that’s why,” she writes. “They could afford to not get paid.” Signing with a major label, charging more than five bucks for a concert ticket, marrying a Beastie Boy—things that prompted accusations of Hanna having sold out—were all decisions tied up with being able to afford health insurance. Her later band Le Tigre largely comes about because that Beastie Boy, Adam Horovitz, suggested she buy a drum machine because it only cost $40 but was worth $600.

At the same time, Hanna acknowledges her own privilege in the industry and in life. When Cobain is annoyed that she gave him a book, she realizes he’s used to being thought of as a poor townie around Olympia, while Hanna is someone who got to go to college, albeit after talking her way in with the admissions office following an initial rejection. Beyond personal slights, a lot of Rebel Girl is a look back on how the riot grrrl movement was largely a white space and how Hanna contributed to that. Apologies and excuses could come off as annoying, but as a writer she maintains a tone of simply wanting the world to be less shitty.

Her accounts of the mid-’90s to now breeze through the years in short chapters: snapshots, turning points, moments of healing. “The Courtney Thing” recounts the infamous incident at 1995’s Lollapalooza when Courtney Love punched Hanna, fueling “catfight” headlines. Hanna writes that, prior to that day, she’d never met Love. The real tragedy of that day, though, might have been arriving late and missing Sinéad O’Connor’s performance: “The Lion and the Cobra had been my ‘I’m becoming a feminist’ soundtrack, and Sinéad’s songs were living in my skin like pockets of salve waiting to heal me.”

Reading Rebel Girl might make you want to pop in not just your old Bikini Kill tape or Le Tigre CD, but also crank up some Sinéad, go jogging (as Hanna does) to Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, look up ’70s punk band Crass, check to see if the Roseanne episode with Jenna Elfman as a hitchhiking riot grrrl is streaming anywhere (it is, on Peacock), and watch Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains, the 1982 film about an all-girl punk band. When Hanna saw it, at Tobi Vail’s house after an early Bikini Kill practice, Vail’s uncle had taped it off the TV on Betamax. Today, it’s available on Apple TV. But you can also just pick it up at Movie Madness.

Powell's Books hosts Hanna at a ticketed event at Revolution Hall at 7:30pm Thursday, May 23, in conversation with Fabi Reyna, $40.99 admission includes book.