The Purist

IT’S 4 O’CLOCK in the afternoon, six hours after morning rehearsals began, and the main studio of Oregon Ballet Theatre (OBT) is starting to get humid—stickily so. The windows facing SE Sixth Avenue are clouding with beads of condensation; the odor of sweaty feet suffuses the thick air. Dancers pace the edges of the room, long limbs grazing each other, as Christopher Stowell, OBT’s artistic director, signals the dancers to take their marks.

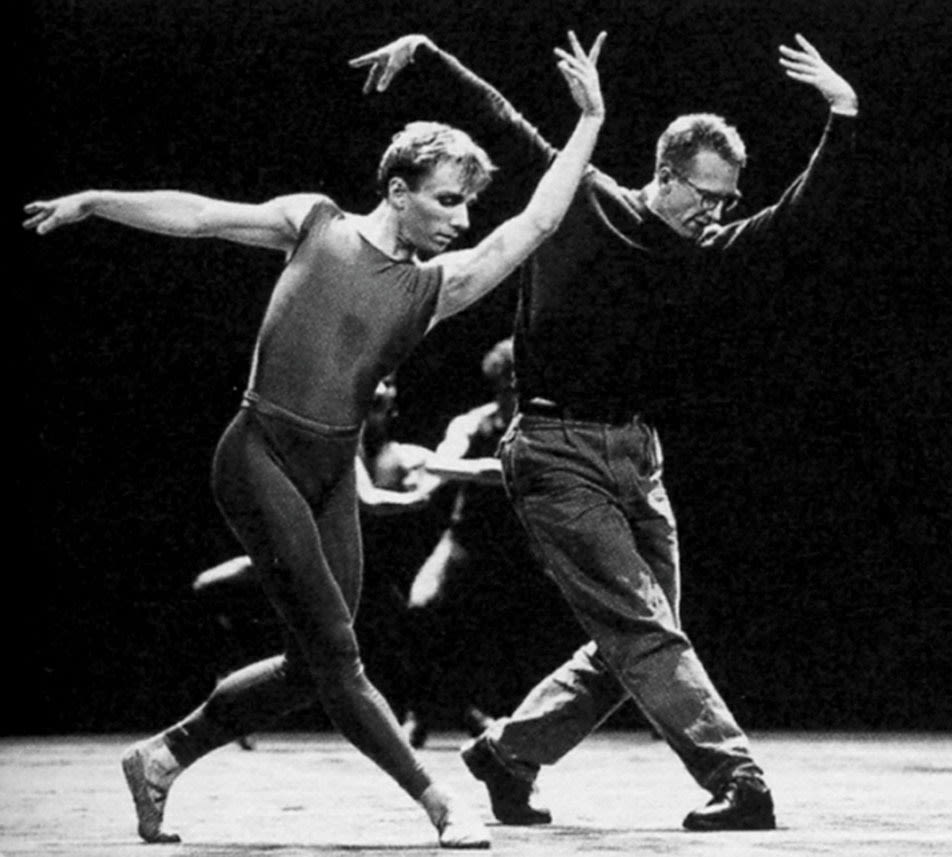

Stowell’s splayfooted stance—heels together, toes apart—and erect carriage evince his own past career as a dancer (the hidden reminders include three herniated disks and an arthritic hip). At age 42, Stowell, a man of medium-small build, with short, slightly receding brown hair and nondescript spectacles, no longer subjects his own body to the rigors of ballet. He has 28 other bodies for that, and right now most of them are running through the first act of Through Eden’s Gates, a vaudeville-inspired dance medley set to composer William Bolcom’s pounding piano rags, scheduled to open in 11 days.

“Five, six, seven, eight! And one, two, three, four, boom-cha-cha-uh!” Stowell counts off in his cheerfully commanding, reedy voice. Ten dancers, their muscles cut like Michelangelo sculpture, explode in an intricate partnering sequence. Stowell interrupts as five male dancers yank hard on their partners’ hands to pull them into piqué turns. “OK, you know what’ll make it look one step better is—guys, once you pull her, if you really go push to the other side,” he coaches, roughly miming the move by jumping to one side as he thrusts his hands in the opposite direction. “One more time.”

Again the dancers burst forth, this time recalibrating the force-distance variables that will make this particular half-second maneuver that much cleaner, stronger, more graceful, more precise.

Developing the talents of the company dancers; directing productions (five per year); setting the training philosophy for the company school; furthering, in all ways, the artistic vision for this city’s $6.5-million-a-year ballet company: Stowell, OBT’s chief creative mind, has a lot to think about in any given fraction of a second. Virtually every decision he makes bears on a big-picture question somehow. How to attract a subscriber base that will help put the company in the black and keep it there. How to adapt ballet’s refined classical traditions—which date to the Baroque era—to fit the cultural context of the present. Often, though, these expressions of leadership come down to judgments about near—incalculably small and insensibly ethereal details: rotating a ballerina’s torso a hair to the left, so that the graceful line made by her raised arm can be better appreciated by the audience; changing the position of her foot so that it drags more fluidly when her partner whisks her across the floor.

As the dancers return to their marks again, Stowell admonishes a couple of apprentices for coming in too early with their tours jetés, a grand leap in which the legs scissor and the body reverses direction midair.

“You wanna really try to go da-da-da-plung,” he emphasizes, glossing the upper-body movements as he lifts and resettles his back foot. The boy and girl obediently take their positions to show him they’ve grasped the timing lesson.

Image: Blaine Truitt Covert

The most alluring thing about ballet is not that it is beautiful or graceful, but that it is unnatural and exquisitely difficult to pull off. Fifteenth-century Florentine and Milanese princes, the sorts of people who bankrolled Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, and 16th- and 17th-century French nobles like Louis XIV, the flamboyant king responsible for the gardens of Versailles, got the tradition rolling with grand spectacles featuring songs and recitations, dancing courtiers, and even men on horses riding in geometric configurations.

These precursors to ballet were personal statements of power and will. But to get from those early potpourris of theatrical excess to, say, Marius Petipa and Tchaikovsky’s 1890 Sleeping Beauty, a three-act ballet performed on a proscenium stage with a professional company of ballerinas dancing on point—and from there, to reach a 20th-century masterpiece such as George Balanchine’s marvel of neoclassical abstraction, Concerto Barocco—has required a different sort of exertion of will. ‘I see ballet as a language’ he says. ‘And it’s a language that’s very difficult to speak, to stick with the metaphor.’

Ever since ballet’s five positions of the feet were codified sometime previous to 1700, the art form has evolved by means of a long, collective drive to perpetuate and better the achievements of previous generations. In Paris, St. Petersburg, London, and New York, it has developed by way of the collaborative toils of innumerable dancers, ballet masters, choreographers, composers, and directors—such that today, when a ballerina rises on point in a swanlike arabesque, it is the weight, and the appearance of weightlessness, of at least three centuries of human effort that rest on her toe. Nevertheless, towering artistic achievement that it is, ballet (which has never developed a common system of notation for movement, as classical music has for song) is both ephemeral and mercurial. At any moment, the modern-day institution of ballet is dependent for its form upon numerous dance companies and associated training academies around the globe, each led by an artistic director, each of whom is responsible for maintaining and improving his particular branch of the balletic flume.

Taken together, the actions of these artistic directors in large part determine the survival of the art. They also give each ballet company a distinct identity. How will the dance training incorporate elements from different stylistic traditions? How will the repertory strike a balance between older works and risky new ones? And how will subscriptions be sold and patrons milked for contributions to pay for all of this?

The latter question is certainly not inconsequential for Stowell, who will mark his fifth anniversary as OBT’s artistic director next month, having set a new company high in spending for ballet productions. But it’s the way in which Stowell has redefined OBT’s artistic identity that has left the deepest impression on observers since he took over from the company’s founding director in 2003. This month, when OBT dancers travel to the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., to perform in the venue’s inaugural Ballet Across America Festival (an honor to be shared with venerable companies such as the Houston Ballet and the Boston Ballet), a large and discerning dance audience will have a chance to see just how this young director has imprinted his own artistic heritage on a ballet company that’s only beginning to come of age.

"He probably thought he fell on the stage when he was born,” says Kent Stowell of his eldest son. That was 1966; Kent was a dancer with the New York City Ballet, working under Balanchine, the most revered American ballet master and choreographer of all time. Kent’s wife and Christopher’s mother, Francia Russell, a former company member, was the ballet mistress. (Balanchine, naturally, was one of the first people to make a congratulatory visit to the Stowells’ West 69th Street apartment after Christopher’s birth. Seeing the 5-pound, 14-ounce infant, he is said to have remarked, “Not as bad as I expected.”)

When Stowell turned 4, his parents moved to Germany to dance with the Bavarian State Ballet in Munich, then went on to become the artistic directors of the Frankfurt Ballet. Stowell went to a German kindergarten dressed in lederhosen; evenings and weekends, he accompanied his parents to the theater. When the family returned to the States in 1977 so that Kent and Francia could take the helm of the then-flailing five-year-old Pacific Northwest Ballet in Seattle, their 11-year-old son, a Tchaikovsky and Mozart fan who had never seen a Dairy Queen, found it difficult to make friends with the neighborhood children in the Bellevue suburbs. But in the classes he took at his parents’ ballet school, he found a familiar environment and a ready-made social life. And at age 14, he decided he’d also found a professional and artistic calling.

Image: Oregon Ballet Theatre

His parents discouraged him: Like his father, Christopher had stiff hips, a severe handicap in achieving “turnout,” the outward rotation of the hips that is essential to ballet’s physical aesthetic. He was also short—and unlikely, at 5-foot-6, to be cast in the danseur noble roles of heroes and princes. “We felt it was a hard profession,” his father recalls. “He had a difficult body—it was not a supple body; it had to be shaped.”

But Stowell overcame his physical shortcomings, traveling to New York during his high school summers to study at the School of American Ballet, the professional academy of the company where his parents had worked 20 years earlier. The fall after graduating from high school, he joined the school full time, and the following spring (despite having been sidelined from class and rehearsals due to a broken foot), he performed starring roles in the school’s annual show. Although the New York City Ballet (NYCB) didn’t offer him a contract—a grave but short-lived disappointment—the incoming artistic director for the San Francisco Ballet (SFB), Helgi Tomasson, did. He hired Stowell, sans audition, based on word of mouth and excellent reviews.

Founded in 1933, the San Francisco Ballet is the country’s oldest ballet company. But it took Tomasson, a former NYCB dancer, to make it a force of national stature—using Stowell as one of his prime instruments. In Stowell, Tomasson saw a dancer who was quick to learn, articulate in his movements, and charismatic. Naturally, given his artistic lineage, Stowell executed Balanchine ballets with flair, displaying the proper cleanness of line and quick-footed musicality. But Stowell’s more traditional roles also were memorable (he pulled off the role of Mercutio in Tomasson’s own Romeo and Juliet with rare “skill and maturity,” Tomasson recalls), and before long, eminent contemporary choreographers were creating roles for Stowell in new works commissioned by SFB. Moreover, Stowell was the beneficiary as Tomasson plucked dancers and instructors from around the globe whose broad range of dance backgrounds enhanced Stowell’s early, Balanchine-influenced training.

By the time he retired from dancing after spending 16 years with SFB, Stowell was a virtuoso dancer. Owing to his intelligence and curiosity, he was also an advanced trainee in the art of ballet directing. He spent the next two years roaming the country (he also detoured through Japan), choreographing and working as an assistant director for regional ballet and opera companies. Then he got a call informing him that Oregon Ballet Theatre was searching for a new artistic director. During the summer of 2002 he crafted a point-by-point, three-year plan for the company, and was invited to begin work on July 1 of the following year.

In a studio painted marigold yellow and sparsely outfitted with a stereo system, a poster bearing a diagram of the human skeleton, and an economy-size bottle of hand sanitizer, Stowell coaches Adrian Fry and Kathi Martuza through a tango-inflected pas de deux, the second act of Through Eden’s Gates. With his strawberry blond hair and easy grin, Fry resembles a Happy Days-era Ron Howard, while Martuza looks wholesomely sexy with her gold cross pendant and heavily plucked eyebrows. As Bolcom’s piano duet, “Paseo,” plays on the stereo, Fry spins Martuza in dizzying circles, assists her doelike leaps, and scoots her around the floor. A mere week and a half before opening night, perfection remains elusive, as Martuza’s foot, meant to summit Fry’s shoulder in a leggy embrace, snags bluntly against his chest. The dancers still have far to go to master the technical aspects of the performance, let alone achieve that extra quality—the palpable chemistry that should roil between the partners—that could make it transcendent.

But while some ballet directors might be sweating nervously at this point, Stowell is calm. No one is groaning, spitting invectives, or sobbing in frustration. Martuza and Fry stand with their hands on their hips, chests heaving lightly from exertion, trading quick notes: They could be playing a leisurely Sunday-afternoon game of pickup basketball while their friend tunes the boom box. The scene reflects an important way in which Stowell has reshaped the culture of OBT.

Principal ballerina Alison Roper, who has been with the company long enough to have trained under Stowell’s predecessor, James Canfield, recalls Canfield’s studio as “a serious environment where mistakes weren’t funny.” But in the first classes she took with Stowell, she says, “people would make a mistake and laugh, and I’d realize, It’s OK. It’s just class. It’s a sport, but you have to have some artistic space, and Christopher allows that.” Principal dancer Anne Mueller, the other company member whose career has spanned the tenures of both directors, concurs. “People feel happy and light,” she says, “but at the same time lots of really good hard work is getting done. That’s a difficult balance to strike as leader.”

Much of that “work” involves developing a sense for how to respond intuitively to music, an ability that is crucial in creating performances that feel vividly alive. In class, dancers practice movement combinations that use syncopated rhythms; in rehearsals, they are accompanied by a live pianist. Onstage, they must adapt to fluctuating tempos and dynamics, since Stowell has lobbied to fund the expense of a live orchestra whenever possible.

“Philosophically,” Mueller says, “when we’re performing he wants us to be very present in the moment, in a very exploratory way. He wants us to be unafraid when we perform onstage, unafraid to go for things, and push ourselves, and not to be the same every time.” This she describes as “a beautiful place to be.”

More visible and talked about than Stowell’s habits in the studio are the changes he has made to the company’s public face—changes that add to the impression that he is the virtual antidote to Canfield (or at least, in the words of Roper, Canfield’s “polar opposite”).

Canfield, a former dancer with Chicago’s Joffrey Ballet known for his commanding physique, sharp intellect, and serious bearing, came to Portland in 1985 to dance with, and soon thereafter to direct, what was then the Pacific Ballet Theatre. By 1989, that company had merged with a competitor, Ballet Oregon, and Canfield, then in his late 20s, became the new company’s artistic director. An exponent of the Joffrey Ballet’s style of freely melding modern and classical dance forms, Canfield sought to attract younger audiences by augmenting classical ballets with edgy, contemporary pieces—ranging from works in progress by OBT dancers to glistening creations by eminent choreographers such as Bebe Miller and Karole Armitage.

But Canfield became best known for the pop-culture-influenced ballets he choreographed himself. Often scored to loud rock music and featuring outlandish costumes or skimpily clad ballerinas performing sexually suggestive moves, these productions shocked old-guard audiences and some feminist-leaning balletomanes to the point that, as Oregonian journalists Bob Hicks and Barry Johnson wrote, “By 1989 [Canfield] felt it necessary to tell the Oregonian, ‘I’m not a female hater or a female beater. I’m not a psychopath.’”

Still, thanks in part to Canfield’s gifts as a teacher (Roper, for instance, credits him with turning her into a “great” dancer) and his deep fluency in ballet’s classical vocabulary, he helped OBT to grow into the accomplished midsize company that it is today. By the beginning of Canfield’s 10th year as artistic director, the company had earned the first of two invitations to perform at the prestigious Joyce Theater in New York, and it had raised enough capital to take title to a new headquarters in a renovated First Interstate Bank building on the corner of SE Sixth Avenue and Morrison Street (it’s still OBT’s home). Yet by the time the 2001-02 season opened with Lady Lucille and the Count, Canfield’s modern-Gothic interpretation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula set to a score by Dead Can Dance—which also included a set piece that the Oregonian described as a “two-story-high phallus”—the tide was turning against him. In February 2002, Canfield announced plans to leave OBT, citing a desire to pursue other creative interests, and though a representative of the board denied he had been pushed out, many were glad to see him go.

Stowell’s exorcism of Canfield’s ghost was immediate, underscored during an early talk for OBT supporters when he declared, according to the Oregonian, “This is a ballet company, not a dance company.” His first season, he replaced 8 of 19 dancers with handpicked successors, hired a new school director, and began the process of overhauling OBT’s repertory, introducing the same type of high-minded classicism that had, broadly speaking, predominated in his parents’ and Tomasson’s companies.

His first season offered 11 company premiêres, including classic modern works by Balanchine and a recent piece by a much-in-demand British choreographer named Christopher Wheeldon, whom Stowell had worked with and befriended while at the San Francisco Ballet. In coming seasons he gradually interspersed mixed-repertory programs of traditional and neoclassical works with lush, evening-length story ballets: densely populated, technically demanding works such as Swan Lake and Stowell’s own A Midsummer Night’s Dream, choreographed to Mendelssohn’s score, that focused attention on the company’s classical technique and its growing corps of artistically mature dancers (a corps that Stowell increased from 19 to, as of this season, 28). The Stowell era had begun.

Seated in a low chair in his OBT office—a former bank vault that one still enters through its original, imposing, foot-thick door—Stowell explains what it is that, in his mind, separates ballet from all other forms of dance, the thing that has kept him in its thrall.

“I see ballet as a language,” he says. “And it’s a language that’s very difficult to speak, to stick with the metaphor. It’s a language that, when people speak it well, makes them pretty special. And to do this well, you have to work hard on it all the time.”

By “language,” Stowell doesn’t mean a glossary of terms: arabesque, pirouette, jeté. He means, quite literally, a system of communication—albeit a kinetic, corporeal one—whose most proficient users, the dancers, constitute a culture unto themselves, complete with their own manners and physical phenotype. In her 1979 book The Magic of Dance, retired prima ballerina Margot Fonteyn got at this ineffable quality when she wrote of the great dancer Vaslav Nijinsky: “At a loss to define his genius, various people used comparisons like ‘half cat,’ ‘half snake,’ ‘a panther,’ ‘a serpent,’ ‘a stallion,’ ‘no man, but a devil.’ It is a curious fact that he was rarely compared to a human being.” According to Stowell, ballet choreographers like himself “get off” on these “basic aesthetic qualities.”

“I don’t want them to look like ordinary people,” he says. “They’re not the horse hanging around the barnyard. They’re, like, the Kentucky Derby-winning horse. They can do things; they have ready at their disposal a physical arsenal.”

Training and caring for a stable of thoroughbreds is expensive, of course. And this struggle to balance lofty artistic ideals with base financial realities weighs on Stowell. To pay 28 dancers their weekly salaries during the performance season; to rent halls, sew costumes, hang lighting, build scenery, and hire musicians for five productions each year; to run a ballet school with 180 students; and to employ a cadre of fundraising, marketing, outreach, and other staff to support all this activity amounts to an annual budget of about $6.5 million.

Like most ballet companies, OBT pays for the bulk of its expenses with a near-even split of earned revenue (from ticket sales and education programs) and donations. And as with arts organizations everywhere, hitting those revenue targets is a yearly gamble. In three of the five fiscal years leading up to 2005-06, OBT posted operating deficits, and it barely covered its expenses in the other two. During 2005-06, the operating deficit reached a $1.9 million nadir when Stowell’s decision to increase the number of annual productions from four to five coincided with the cancellation of $768,421 in previous years’ capital campaign pledges—and fundraising remained stagnant, due at least partly to lengthy vacancies in two upper management positions.

OBT’s current executive director, Jon Ulsh, who was hired in 2006, says he’s gradually been turning the financial boat around; last year’s deficit was just $300,000, and this year he hopes OBT will break even, thanks to steadily rising ticket sales, subscriptions, and private contributions. Still, these are uncertain times for ballet companies all over the country. Since 2001, seven companies with budgets of more than $1 million (in cities such as Oakland, Akron, Cleveland, and Indianapolis) have shut down or cut back operations drastically; by contrast, during the entire 1990s, only one did. John Munger, director of research and information for Dance/USA, a national professional association for dance companies based in Washington, D.C, says that the current rate of failure is “unprecedented.”

Munger posits that philanthropic dollars have been sucked away by an unfortunate convergence of natural disasters and a falling stock market. Now there are signs that many ballet companies are hoping to make up lost revenue by retreating to safer artistic ground—meaning performances that bring more people to the box office. Munger’s preliminary research indicates that last year commenced “an enormous surge toward either classicism or the kind of new work that has built-in name recognition”—ballets created for stories such as Alice in Wonderland or Peter Pan. He’s also noted a surge in “consciously hip, very new” works, choreographed by company members or commissioned through new works festivals, that are less expensive to produce.

{page break}

But Stowell says Portland is an exception to this trend partly because of the broad tastes of local audiences. “I don’t feel forced into … doing as many performances of Swan Lake as we can,” he says. In April—the same month the Atlanta Ballet drew national media attention for Big, a production featuring classically trained dancers leaping and spinning to the rhymes and beats of Big Boi, half of the hip-hop duo OutKast—OBT was doing Balanchine. In the next few seasons Stowell hopes to introduce works by Twyla Tharp and Mark Morris, the great Seattle-born contemporary choreographer, into the company’s repertoire, which will further broaden OBT’s foundation of modern classics. Neither Peter Pan nor a festival of new works are part of the plan.

But even if financial worries aren’t driving Stowell’s artistic decisions, they are not far from his mind. Asked what he would do with a $10 million gift, he replies that he likely would put it into an endowment. “We’ve gotten a lot done in the five years I’ve been here,” Stowell says. “We have a whole new repertory; we have developed relationships with important artists who are continuing to come back and make new work for us; we are attracting a really high quality of dancer from all over the world. So we have real building blocks in place.” Now, he says, his focus is on “sustainability.”

“How can we make this an institution,” he muses, “and find ways of sustaining all the work we’ve done—and increase it, of course—but also have the support we need there, so it’s not threatened to be ripped out from underneath us?” That, of course, is the eternal question.

On May 8, it was as if Stowell’s past itself had descended on the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall: Four West Coast ballet companies convened there for a rare group performance presented by Portland’s White Bird, and for a bit of friendly artistic rivalry centered around the evening’s theme of “contemporary ballet.”

Tomasson, Stowell’s former director at San Francisco Ballet, was there, defending the classical fort—and displaying what a $42 million budget can buy—with his Concerto Grosso, a withering fusillade of virtuoso leaps and spins by five male dancers. Peter Boal, the leader of Seattle’s Pacific Northwest Ballet since Stowell’s parents retired in 2005, replied with Shindig, a whimsical parody of ballet’s fussier conventions choreographed by one of the company’s dancers. Toni Pimble of Eugene Ballet Company took up the social protest flag with Still Falls the Rain, her modern-dance-inflected piece inspired by the story of a young couple’s late-1990s death by stoning in Afghanistan.

As for Stowell, he claimed his characteristic, classically attuned middle ground with Christopher Wheeldon’s Rush, the quirky, athletic, dance-for-dance’s-sake ballet that OBT will perform again this month at the Kennedy Center. It was the only company première of the night, and a few minutes before the curtain rose, Stowell was backstage, exhibiting his typical high tolerance for last-minute uncertainties.

His dancers, scattered across the floor, adjusted their costumes (one ballerina had discovered that hers was on backward) and made runs to the wings to consult on details of head- and hand-positioning with the visiting ballet master. Stowell mingled among them, offering words of encouragement and light quips. Then, addressing the group, he shared one last reminder: “Dance big, and have a great time, everyone!” The dancers raised their hands in a light patter of good-luck applause. Stowell exited through the stage door to watch the show.