The Shape of Memory

ON A CUSP-OF-SPRING SUNDAY MORNING in March, a light wind riffled the tall, dry grass ringing the strange, concave crown of Chief Timothy Park, an island dune that hunches out of the Snake River near the twin cities of Lewiston, Idaho, and Clarkston, Wash. A bowl of bare earth, about 300 feet in diameter, had formed there—a natural crater, perhaps, or a manmade rubbish pit—and Maya Lin, the celebrated designer of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC, stood at its lip. A handful of recruits from the Portland landscape architecture firm GreenWorks had arrived before sunrise, toting lengths of flexible PVC pipe to mark future seating terraces in the outdoor amphitheater she envisioned in the crater’s place. Lin, a slight 47-year-old dressed in studiously plain black jeans and a black rain shell, regarded their progress with dismay.

“This was supposed to have been cleared away,” she scolded to no one in particular, gesturing at piles of brush that had accumulated in the pit. “This is going to be a complete waste of time.” She picked her way down the slope.

Time is relative, of course. More than seven years had passed since a group of Oregon and Washington residents, primarily Native Americans, had petitioned Lin to design an extraordinary memorial, the Confluence Project. The seven landscape artworks, sited at major junctures of the Columbia River and its tributaries, would plot the final leg of Lewis and Clark’s journey, from Washington’s eastern border to the Pacific Ocean, in conjunction with the bicentennial anniversary of the 1804-6 expedition. But instead of recapitulating the epic journey from the Corps of Discovery’s point of view, the artworks would capture the perspectives of the people who were already living there when the explorers arrived. Sited in public parks—or more typically overtaking them—Lin’s designs would incorporate fragments of text (Native American myths, Lewis and Clark’s journal entries) and functional sculptures (a bird blind, a land bridge, a fish-cleaning table) to evoke a landscape and a way of life submerged in time and memory.

Lin (far right) plots the placement of the Chief Timothy Park listening circle with the Confluence Project design team during a site visit in March 2007.

Perhaps the Project’s plodding pace partly explained Lin’s impatience. A year after the bicentennial commemoration had tapered off, only one of her seven designs had been built (at Washington’s Cape Disappointment State Park in April 2006). And at least another year was expected to pass between that first ribbon-cutting ceremony and the next one, at the Vancouver National Historic Reserve, directly across the Columbia River from Portland, where a mammoth pedestrian land bridge will be dedicated on the 16th of this month. Owing to the astounding complexity of a design process involving input from dozens of research and technical consultants and representatives of at least eight native tribes, the project was materializing over what could easily become the course of a decade.

Lin also faced immediate time pressures. Earlier that morning, she had arrived late for our scheduled 6 a.m. interview, in the dining room of the Lewiston Red Lion Hotel, because she’d been packing and repacking for her trip to China the following day, where she was scheduled to work on a project involving the “greening” of an existing university. On the breakfast table, the front page of the Seattle Times displayed a photo of Lin, haloed by sparks, working in the hot shop of the Museum of Glass in Tacoma, where she’d just spent a two-day sculpture residency. After her site visit at Chief Timothy this morning, she would speed some 260 miles west to an afternoon blessing ceremony at the most politically knotty of the Confluence Project sites: Celilo Park, where Celilo Falls, for eons a Native American fishing and trading center, had been inundated by the Dalles Dam in 1957.

Atop the summit of Chief Timothy Park, Lin’s demeanor lightened as she charged into the fray of people and dirt. A three-person documentary video crew, hired by Confluence Project organizers, loped along behind her, carefully avoiding tangles of branches, as she delivered brusque greetings and crisscrossed the rugged depression. Calling out questions and opinions (“I’d call this shape a warped potato chip”), ordering photographs taken, vehicles moved and sketches drawn, she pulled Nez Perce landscape designer Brian McCormack alongside to vet the contours of the seating terraces for cultural sensitivity and finally, perched atop a black minivan, directed the GreenWorks crew to pull the circle of PVC pipes representing the lowest section of the amphitheater a couple of feet southeast.

Maya Lin with Nez Perce tribal elder Horace Axtell at Chief Timothy Park in 2005.

During our brief breakfast meeting, Lin had explained that of the seven Confluence Project sites, Chief Timothy best symbolized the pristine state of the landscape before European settlers arrived. The relatively untouched, 198-acre wildlife preserve offered magnificent views of a glistening river canyon cutting through a field of rolling Palouse hills (despite the fact that dams had turned the once-wild Snake into a slow-moving industrial channel for the nearby Clarkston-Lewiston port). Besides gaining the amphitheater—Lin called it a “listening circle,” its form inspired by a Nez Perce blessing ceremony that had occurred there two years earlier, after the site had been chosen for the project—the park would be landscaped with native plants. It would also receive a new name (still to be determined), reflecting what Indians might have called the area in days past. Timothy, after all, was considered a traitor by many Native Americans, as one of the first Nez Perce leaders to convert to Christianity and to adopt the white man’s agricultural ways. Lin’s greatest hope for the park, she said, was that the Nez Perce would use it on a regular basis for ceremonies—symbolically reclaiming the land for the tribe.

That sentiment was echoed by Horace Axtell, the tribal elder who initially guided Lin to the park and later led the blessing ceremony there. I’d met with him a year and a half earlier. An old man with a kind, weathered face and two long braids, he’d observed that the Confluence Project was already having an effect. Area schoolchildren had participated in an outreach program, creating their own commemorative sculptures. And Lin’s design for the park would hopefully initiate a long-deferred discussion.

“If things go the way it’s going here, maybe we’ll be able to tell the story of our people,” Axtell ventured. “And people will understand that we were the ones who were here before—when our language was the only one heard in the canyons.”

This month marks the 25th anniversary of the dedication of Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial. That minimalist granite rift set into the lawn of the National Mall changed Americans’ notion of what a memorial is. With the Confluence Project, Lin reenters the memorial fray on a field still trembling from the impact she made a quarter century ago.

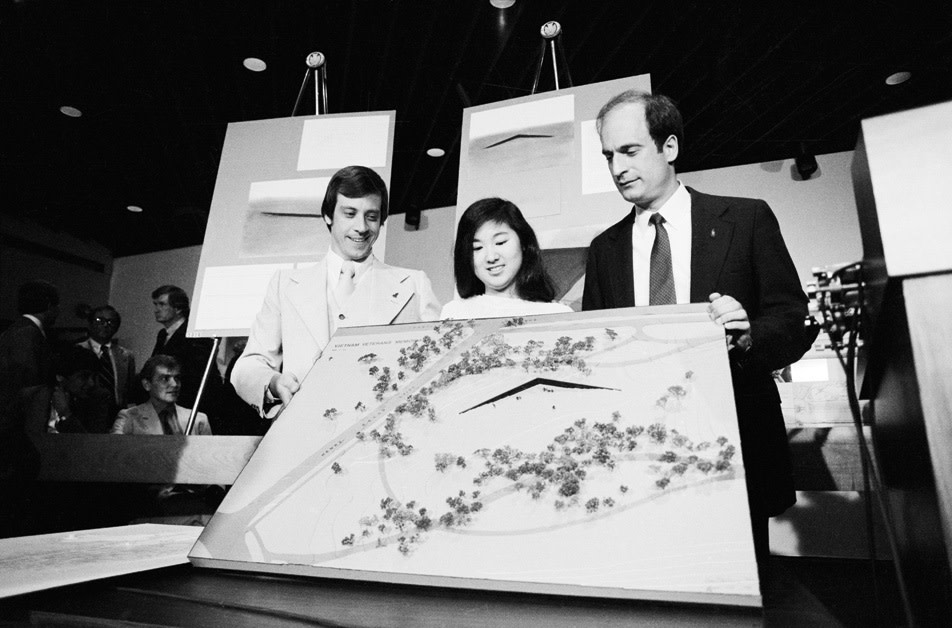

In 1981, 21-year-old Maya Lin presents her winning design for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. With her are Jan C. Scruggs, president of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund (left), and Bob Doubek, project director (right).

Lin grew up in Athens, Ohio, the daughter of intellectuals who had fled China on the eve of the Communist revolution; her mother taught English and Asian literature at Ohio University, and her father was the dean of the College of Fine Arts. She entered the Vietnam Veterans Memorial design competition while participating in a tutorial on funereal architecture when she was a 21-year-old undergraduate at Yale.

In a sense her design proposal was nothing but a literal interpretation—albeit a brilliantly literal interpretation—of the competition guidelines, which prescribed that the memorial be “harmonious with the site, apolitical and conciliatory,” and that the names of all 57,661 American war casualties be used. Lin submitted several pastel sketches showing two polished granite walls embedded into the earth and sloping down toward a central point, along with an essay specifying that the names of the war dead be inscribed, in columns, in chronological order by the dates of their deaths. By entering this “rift in the earth,” she wrote, the living, while seeing their own reflections mirrored in the polished granite, would be brought into a “concrete realization” of the dead.

In a blind competition judged by a blue-ribbon panel of architects and sculptors, Lin famously beat out 1,421 other candidates. Yet for some time it was unclear whether the jury’s decision would prevail, as outraged veterans and others—shocked either by the stark design or by Lin’s race, gender and age—lambasted the proposed memorial as a “black scar” of “sorrow and shame” and hurled epithets such as “gook” at Lin (even though she had no Vietnamese ancestry).

Anyone old enough to watch television in 1982 may recall the image of Lin, a slightly awkward young woman with waist-length, frizzy hair, dressed in a puff-sleeved suit with a bow at the neck, coolly and determinedly defending her creation on ABC’s Nightline and at official hearings of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, which had final say over the design. With the influential support of then-secretary of the Interior James Watt, her opponents eventually forced a compromise: A separate memorial would be built, consisting of a bronze statue of three soldiers and an American flag, at the entrance to the memorial site (and at a respectful distance from Lin’s artwork).

As soon as the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was unveiled, the dissenting voices were quieted. In coming years millions made pilgrimages there to leave offerings and to make charcoal rubbings of the names of lost loved ones. It seemed that the genius of the memorial lay in its ability to withstand conflicting interpretations: Opponents of the war saw a clear political message in the gravelike dugout, while those supportive of or ambivalent toward the conflict found a peaceful place to engage in private mourning. Art historians and critics recognized a different achievement: Though a few minimalist Holocaust memorials had been built in Europe and Israel at least as early as the 1950s, this was the first American memorial of its kind, and the simplicity of its architectural statement was singular.

Still, the premature fame and notoriety dogged Lin’s psyche. She repressed the memory of her tumultuous 21st year until her late 30s, when she sat down to watch the documentary film Maya Lin: A Strong Clear Vision, and recollections of the television cameras and angry letters flooded back. By that time she had designed two more public monuments, the Civil Rights Memorial for the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Ala., and the Women’s Table at Yale University, which commemorated the institution’s female students. In the ’90s Lin set to work reestablishing her artistic identity, designing everything from environmentally sensitive buildings to enormous earth works, even a line of furniture for the modern design studio Knoll. She also became an outspoken environmentalist. In Boundaries, her autobiographical book published in 2000, Lin announced that she had one final memorial in her; the self-originated work would take the form of seven markers, located at points around the world, that monitored the health of the planet.

Meanwhile, the public’s embrace of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, and of the catharsis it engendered, had broad consequences. Lin’s vocabulary of stone and value-neutral text became a new lingua franca of public art. And it prefaced an era of frenzied memorialization. By the mid-’90s, the Korean War Veterans Memorial had been erected on the National Mall, and a World War II memorial was being planned nearby. Moreover, Americans were constructing memorials in cities and towns all around the country, to mark not only wars and events of major national consequence, but also tragedies of a smaller scale (the TWA Flight 800 disaster, the Columbine shooting), almost before mourners had a chance to bury the victims.

It was a few months after the Oklahoma City National Memorial’s construction—and less than a year after the publication of Boundaries—that Lin seems to have reconsidered her fate vis-à-vis memorial art. She accepted the Confluence Project commission in November 2000 because of “who was asking,” she likes to say, somewhat obliquely. Ten months later, attackers felled the World Trade Center towers and she answered a call to serve on the design competition jury for an eight-acre monument at Ground Zero. The decision had been wrenching, she indicated to me in March.

“After 9/11, you wanted to help, and if that was something I could help with, absolutely I was gonna be there,” she said. “But at the same time, I also knew it was almost going to be a matter of erasing 15 years of conscious effort on my part; and it’d be, ‘Oh my God, that’s the girl who did the memorial.’”

It wasn’t as if the world had forgotten. The following year, with Lin’s support, Michael Arad and Peter Walker won the World Trade Center Site Memorial Competition with a design called Reflecting Absence. Two massive reflecting pools would be excavated in the footprints of the towers, the walls of the pools inscribed with the names of the dead. The design bore an obvious resemblance to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, and Lin’s name immediately resurfaced in public debates about whether the typology her “unsurpassed” monument had introduced two decades earlier might finally need updating. Her name made the papers again in 2004, when Friedrich St Florian’s National World War II Memorial was finally dedicated. With its pillars and bronze eagles, the classically inspired plaza was an obvious snub to “the American style of tasteful abstraction” associated with Lin.

Now, with the Confluence Project, Lin reassumes her star-making role in a drama ripe for reinvention. And as the saga of America’s, and Lin’s, love-hate affair with memorial art continues, the country can expect to rethink its notions of the genre once more.

A $12.25 million pedestrian land bridge, shown here under construction in October, will arc over a highway, reconnecting the Vancouver National Historic Reserve with the Columbia River.

On a wall behind Jane Jacobsen’s desk hangs a T-shirt showing a photograph of four Indians holding rifles. “Fighting Terrorism Since 1492,” the slogan reads. Next to it is a wooden paddle engraved with the words, “Congratulations on state funding for the Confluence Project. Now we’re up a creek with a paddle.”

Jacobsen, the executive director of the Confluence Project, works in an old brick building a few blocks from the Vancouver National Historic Reserve—once an early-19th-century trading post presided over by the Hudson’s Bay Company and later a U.S. Army fort—on the north bank of the Columbia River near downtown Vancouver. When I met with her there last fall, the girlish 58-year-old, who wore a plump smile and a halo of sandy curls, recalled that when plans were being laid in 1999 for the national Lewis and Clark bicentennial commemoration, the mood was celebratory.

Jacobsen, who was then directing the General George C. Marshall Lecture Series for the National Historic Reserve Trust, found the prevailing “Stephen Ambrose” version of the Lewis and Clark story unsatisfying. In the midst of her workdays she had casually befriended some of the Nez Perce Indians who came to the reserve grounds each year in April to honor the grave of an infant who had died there during the Indian Wars of the 1870s, when Nez Perce Indians were held captive at the fort. She thought Lewis and Clark’s legacy—instrumental as it was to the Euro-American resettlement of the Pacific Northwest—might be viewed differently by her Indian acquaintances. After mulling this over, she called David Nicandri, the director of the Washington State Historical Society, who was coordinating bicentennial events for the state, to propose a bold idea: What if they were to commission a series of artworks examining the Lewis and Clark legacy from the Native American perspective? And what if the artist were Maya Lin—a figure who had proven so adept at reconciling differing intranational myths?

Nicandri laughed. By an odd coincidence, Antone Minthorn, chairman of the board of trustees of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, had called from Pendleton minutes earlier with the same idea. Nicandri suggested they both talk to Nabiel Shawa, city manager of Long Beach, the community on the Washington peninsula near where Lewis and Clark had finally reached the ocean. Shawa related to Jacobsen that he, too, had been thinking, wishfully, about a major project involving Maya Lin.

For Jacobsen, it was too much of a coincidence.

“You can’t let go of an idea like that. It’s like catching a falling star,” she recalled last fall.

With the help of Minthorn and other tribal representatives they recruited, Jacobsen petitioned Lin for a year and a half (sending letters and an ambassador to her Manhattan studio—at one point even mailing a box of stones, shells and feathers gathered from various parts of the region in a last-ditch effort to get her attention). Then her real work began. She founded the nonprofit that bears the project’s name, involved scores of political stakeholders and research consultants, and called upon private philanthropists, foundations and state and national legislators to raise the $27 million it will cost to complete and endow the project. (Despite the fact that two of the artworks will be on the Oregon side of the river, the Oregon State Legislature had at press time committed no money to the project, compared to the Washington Legislature’s $8 million.) She still has $4.5 million left to go. “It’s not like asking for help purchasing a Renoir,” she notes. “It takes awhile for people to comprehend this story of the Pacific Northwest.”

As we walked the grounds near her office, Jacobsen noted that the reserve itself—today a haven for nonprofits, small businesses and artists’ lofts—exemplifies just how complicated the story is. Even before it was developed by Hudson’s Bay, it had been an international trading ground for native people; they converged there from points along the Columbia and Willamette Rivers and from the Klickitat Trail, which extended east beyond the Cascades.

The pedestrian land bridge that the Confluence Project was readying to build there, designed by Seattle-based Native American landscape architect Johnpaul Jones in consultation with Lin, would arc over the highway that runs parallel to the river, reconnecting the reserve’s grounds to the riverbank and reinstating the connection between the land and the water. Near the water’s edge, Lin would create an artwork representing a treaty table.

“It’s all woven together,” Jacobsen said. “This whole place is incredibly deep with history.”

As is the entire river system that Lin is in the process of subtly reshaping—in an obstacle—ridden attempt to meaningfully bring that history to the public’s attention.

Visitors to Lin’s installation at Cape Disappointment State Park traipse along a pathway inscribed with landmarks noted by the Corps of Discovery en route to the Pacific.

The ribbon-cutting ceremony for the first completed Confluence Project artwork took place on the afternoon of April 22, 2006, a warm, cloudless day on Washington’s Long Beach Peninsula. A crowd of 250 or so celebrants gathered in a parking area next to the boat launch at Cape Disappointment State Park, near the presumed site where Lewis and Clark first gazed upon the Pacific Ocean.

A few hundred yards away, a stream of visitors wandered along two unfinished commemorative pathways leading from a parking lot toward the ocean through a sea of fine gray sand and freshly laid bark dust dotted sparsely with native seedlings. One oyster shell-covered path led to a cul-de-sac, where a circle of weathered cedar logs, or “totems” as Lin calls them, ringed a 225-year-old tree stump, evoking the seven directions recognized by Native Americans of the region (north, south, east, west, up, down and within). The other arced toward the ocean; its concrete pavers were inscribed with the names of the tributaries of the Columbia River, which Lewis and Clark recorded on their journey; numerals and directional abbreviations noted each tributary’s distance from the river’s mouth, along with other locational data; and blank pavers represented the distance, approximately to scale, between the tributaries. This created the effect of retracing the footsteps of the expedition in miniature.

Onlookers exclaimed, “Cool!” and, “Honey, did you see this?” as they proceeded along a conventional asphalt path from the parking lot to the boat launch area, where the other portion of Lin’s work guarded the water’s edge: a hunk of basalt, outfitted with a fully plumbed sink and inscribed with the Chinook creation myth. It was a wry update of a cruddy, stainless-steel fish-cleaning station that preceded Lin’s redesign in this location. The myth told of a thunderbird, the creator of humankind, that took shape from a fish cut the wrong way—across its side, instead of down its back.

A lone protestor had planted himself to the left of the podium. A stocky, bearded, middle-aged, apparently Caucasian man, he wore a Chehalis basket on his head and a blue-and-red felt cloak. He held aloft a series of signs: “_Kais_! Not Cape ‘D,’” “_Yakaill Wimakl_, not Columbia River,” “Maya, why do you immortalize U.S. theft?” and “Can an artist be a prostitute for U.S. colonialism?” He seemed to lack sympathizers, and a Chinook I spoke with later confirmed the obvious: that he was a wannabe Indian. But his presence seemed to affirm the event’s historical weight.

The speeches began. Jacobsen welcomed the diverse crowd and expressed hope that Lin’s redesign of the park would mean “whatever you need for it to mean to make this world a better place.” The speakers lauded Lin’s near-oracular abilities as an intercultural translator—Jacobsen quoted one of the Indians who’d traveled to New York to meet with the architect: “My words come from my heart to my eyes, my eyes to your eyes, your eyes to your heart”—and her international notoriety. Next up was former Washington governor Gary Locke, like Lin a Yale graduate and a fellow member of Committee of 100, an advocacy group composed of influential Chinese-Americans. Locke, who had been instrumental in securing Lin’s involvement in the project, predicted that people would “come to the sites because of her stature and fame,” pointing out that “no other state can claim as many artworks by Maya Lin.”

After a hokey poem about the ocean by fisher poet Dave Densmore, Lin herself appeared, dressed in a black peacoat and sunglasses and flanked by her two similarly attired young daughters, and gave a brief overview of the artworks. Then came Chinook tribal chairman Gary Johnson, who recited a traditional prayer. A group of Chinook drummers dressed in cloaks resembling the protestor’s beat a mournful song, drowned out for a moment by a droning motor and caterwauling yeeee! from a passing speedboat.

On the way out, I stopped at the park convenience store to buy a soda for the road. Greeting me was a display of various Lewis and Clark tchotchkes—spoons, T-shirts, a cookbook, stickers (the only package remaining featured images of Sacajawea and the slave York, and it seemed to have been sitting there a long time)—which were, evidently, the competing narratives against which Lin’s artwork would be appraised. I asked the woman at the counter what she thought of the project. Would it attract more tourists to the park?

None of the other bicentennial stuff had, she said, but at least it would give people who were already there something else to see.

“People here don’t take care of things. The fish-cleaning table, people will use it. I can see it all covered in fish guts, and the edges—they’re squared, right? They’re probably going to get chipped off.”

Besides a rather profound cynicism, the statement expressed a misunderstanding of Lin’s intention that the table actually be used. But as I considered correcting the woman, she reappraised the relative virtues of her fellow man.

“Or maybe—who knows? Maybe they’ll keep this one thing nice.”

Salmon fillets pile up on Lin’s basalt fish-cleaning table at Cape Disappointment State Park, which is etched with the Chinook creation myth.

Image: Andrew Brahe

A few days before the Cape Disappointment ribbon-cutting ceremony, Lin emerged from a back room in the underground exhibition hall at the University of Washington’s Henry Art Gallery and assumed a wide-legged stance beneath a room-sized, suspended grid of aluminum tubing crumpled to represent the contour of a sea floor. The morning press preview of Maya Lin: Systematic Landscapes, Lin’s first major art exhibit in eight years, had drawn a dozen or so journalists who gathered around her expectantly.

“This is no different from what a landscape painter of the 18th or 19th century would do; we just get to see nature with different tools,” Lin explained, leading the press entourage through galleries filled with more scale models of major geographic forms—ocean floors, mountain ranges, rivers—rendered in materials such as particleboard and sterling silver, and the pièce de résistance: a room-sized mountain formed of hundreds of sustainably harvested hemlock two-by-fours stood on end. Lin’s interpretive commentary would be duly transcribed in vaguely laudatory features in major art and architectural magazines. (Her sculptures “allude to some of the world’s most endangered ecologies, though you might not know it from the pristine works, surfaced in birch veneer,” wrote David Sokol for Architectural Record.)

Lin’s celebrity status in the art world is more or less fixed, but the polish wore thin for a moment several months later in October, after Philip Kennicott, culture critic for the Washington Post, attended a similar lecture by Lin at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The following Sunday he published an editorial titled, “Why Has Maya Lin Retreated from the Battlefield of Ideas?” in which he accused her of having morphed from a “local hero” to an “apolitical and irrelevant environmental artist” who “makes bumps in the earth and little Zenlike paths in public gardens.” He condemned her as arrogant, moreover, for refusing to discuss either her own past as a monument maker or the current state of American memorial art.

As Lin has attempted to throw off her “monument maker” typecast, she has indeed worked diligently to remake her image—albeit in terms that make a fetish of ambiguity. Her self-characterization as an artist who “exists on the boundaries” finds support in her work: Since the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, she has designed contemplative buildings, cerebral sculptural installations, even a 1,600-foot-long, undulating berm in a cow pasture in Sweden. Yet her insistence on not being pinned down seems to have contributed to a situation in which detractors and fans alike interpret her work in the blandest possible terms.

Beneath all the rhetoric, however, her art tells its own obstinately compelling—and politically relevant—story. Even Kennicott should be impressed that 25 years after the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Lin has embarked on a project even more ambitious than memorializing the tragic consequences of an unpopular war abroad—that is, memorializing the devastating cultural and environmental impact of a celebrated conquest at home.

The almost incomprehensible complexity of the Confluence Project can be partially conveyed by Lin’s process of redesigning a portion of 284-acre Sacajawea State Park. Her makeover of this triangle of grass and picnic tables, which sits under a canopy of grand old sycamores at the Columbia-Snake confluence five miles southeast of Pasco, Wash., involved everything from disinterring ancient languages to assessing the mechanics of weedwhackers.

An early meeting to generate input for the project was held on a cloudy morning in October 2005 in the conference room of the Clover Island Inn, a graying edifice of drab late-’70s modernism a couple miles from the park. Lin, Jacobsen, Minthorn, several other elders of the Yakama and Umatilla tribes, landscape architect Johnpaul Jones and a few buttoned-up employees of the Army Corps of Engineers (which owns a portion of the park) took seats around a broad square of folding tables, and Minthorn rose to read a prepared statement.

“I don’t think I’ve ever really spoken about the event of Lewis and Clark, and the Treaty of 1855, and the impact that those events had on the tribes of this particular region, what we call the Sahaptian tribes: Warm Springs, Yakama, Nez Perce and Umatilla,” he began. Then Minthorn, a longtime tribal activist and a retired land-use planner, sketched the tragic arc of his people. After Lewis and Clark passed through the tribes’ homelands, the arid steppe land of present-day southeastern Washington, traders, missionaries and homesteaders arrived, he explained. Violence broke out in the 1840s, quelled by the Walla Walla treaty in 1855; the government abrogated the rights promised there, and the tribes were gradually decimated and impoverished. It was “a long fall in a very short time,” Minthorn observed, referring to the 150-year decline of his 10,000-year-old culture, but his people remained “determined to recover and rebuild their tribal nations.”

More speeches ensued, and then Lin spoke up: “I don’t think you can return back in time,” she ventured. What she hoped to do was to restore some of the native vegetation, to give visitors a sense of the tribes whose homelands overlapped the park and to convey that the river confluence had served as a transportation hub and trading ground. The artwork had no form yet, and she was primarily here to learn: How did the tribal leaders feel, for example, about her idea of incorporating written words from native languages into the park, even though the languages had existed primarily in spoken form?

Lerena Sohappy, of the Yakama Nation, replied that unfortunately, of the 14 languages and dialects once used by the 14 bands of the Yakama Nation, most were all but extinct.

Roberta Conner, director of the Tamástslikt Cultural Institute, a museum devoted to the history of the three tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (the Walla Walla, the Umatilla and the Cayuse), said she’d struggled with the question of how to represent languages when designing the institute’s exhibits. The Cayuse language had presented a particularly complex challenge. Owing to the tribe’s decimation by disease and warfare, many members had intermarried with other tribes, primarily the Nez Perce; as a result, most people of Cayuse descent who spoke an ancestral language used a version of Nez Perce. That language itself, unfortunately, was poorly documented. “We have a small dictionary of about 400 words. It’s really just a vocabulary list; it’s not a language.”

Lin’s search for an earlier name for the river confluence at Sacajawea State Park raised similar doubts.

“It’s certainly not Sacajawea,” said Sohappy, chuckling.

“Our traditional leaders thought of Sacajawea—I don’t want to say as a traitor, but she was not associated with Native Americans,” concurred Phillip Olney, then-chairman of the Yakama Nation General Council.

In any case, Conner added, there would have been many names for the confluence, including, most likely, separate names for cliffs and for the water. Nearby features—a mountain, for example, or an area where sunflowers grew thickly—might also have been used to refer to the site. “The Daughters of the American Revolution had more to do with the naming of the park than anyone,” she said.

The tribal representatives also couldn’t agree upon a single name for salmon, the sacred lifeblood of the Columbia River peoples. Various names might have applied to the spring chinook, fall chinook, summer chinook, sockeye, coho and salmon that go up different rivers. Furthermore, although salmon were important to the tribes, so were other fish—suckerfish, eels, steelhead, crayfish, mussels. And ultimately Celilo Park would be the more appropriate place to address the salmon issue. The two-hour meeting ended with nothing significant resolved.

But 17 months later, in March of this year, the design for Sacajawea State Park had progressed considerably. Lin had decided she wanted to create a series of “story circles.” Massive rings set in the earth, they would represent themes such as trade, seasonal plants and salmon. One, symbolizing a longhouse, would likely be inscribed with the names of the tribes of the Columbia Plateau.

The principal members of the creative team met to hammer out final details in a high-ceilinged conference room at the Washington State History Museum in Tacoma—Jacobsen; Jones; a four-person research team headed by Betsy Henning; Dylan Farnum, an artisan from the Walla Walla Foundry; and Lin, who, just in from New York, was suffering from jet lag.

“My fantasy is to get a pure ring of bronze,” said Lin, seated at the head of the table, pulling a gold wedding band from her finger. “It either pops down”—she mimed sinking the ring into the ground—“or pops up”—she mimed setting the ring atop the ground’s surface.

Unfortunately, it was against the law to dig into the ground. In one of the more ironic technical challenges faced by the project, the park was an archaeological heritage site. To make it look as if the rings were sunk below grade, Jones and his team would need to figure out how to build up the soil and regrade it to appear natural. And this wasn’t the only technical sticking point. It was unclear whether the rings would actually be made of bronze, versus stone or concrete, or how thick a ring of welded bronze had to be to hold its shape. Or exactly how big Lin wanted the letters to be, so that Henning could choose quotes of appropriate length to inscribe inside the rings. Or what would be placed inside the rings: Gravel? Mowed grass? High plateau grass? Would a weedwhacker be likely to put scratches in the artwork?

There was also an air of anxiety emanating from the research crew regarding matters of symbolic content. Lin’s request for a list of the tribes that had frequented the site was virtually impossible to fulfill, in part because so many of the tribes had been nomadic, and in part because of the sticky politics of naming, the researchers informed her. Moreover, Jacobsen was concerned that “they” had expressed concern about the placement of the longhouse.

“Who are ‘they’?” Lin asked, her voice rising in frustration.

“The elders,” the researchers mumbled nervously.

Three days later, at the Red Lion in Lewiston, Henning summed up one of the many challenges presented by the project. Not only was there no way to identify conclusively all the tribes from near and far that had used the site, but the location to be commemorated also had no definitive geographic identity. “Maya would like a list of the tribes,” Henning said as she raised one finger, “that lived_”—she raised another finger—“_there.” A third finger went up. “There is nothing about that statement that is achievable.”

My last interview with Lin in March, which took place following the Chief Timothy Park site visit in the backseat of a minivan piloted by Henning, offered a final chance to elicit her comments on how the Confluence Project related to the larger story of American memorial design, a story in which she had played such a famously pivotal role. To that end, I asked her how she’d sum up what she wanted to achieve with the project.

It had always been a mouthful, she replied.

“I’m asking you to reflect on what we’ve done, where we’ve come from and where we are going,” she continued. “At the same time, that’s almost too simplistic. I think for the tribes it’s about giving them a sense of homeland, and a sense of feeling that people will know that this is their place, this has been their place for thousands of years. There is something very important about telling what I call the ‘deeper’ story of a place. If you want to say that Confluence as a whole will give people a deeper understanding of the Columbia River system—and not just from the history of men, but from the history of the geology and the ecology of the place—that might be the better summation.”

Lin seldom, if ever, uses the word “memorial” to refer to the Confluence Project. She prefers the term “memory work,” indicating that the artworks are meant to inspire reflection on the past rather than to mourn who or what’s been lost. Many of the seven works will subtly address loss, she acknowledged—the inundation of fishing grounds by dams, the broken treaties, the transformation of the river into “glorified lakes,” the extinction of species, even global warming—but against a backdrop of restoration. She categorically rejects the dismal, which is why she had chosen to create an artwork at Chief Timothy Park, a wildlife preserve, rather than at a previously proposed site, a paved industrial lot at the actual confluence of the Columbia and the Snake. The buried land, she said, “broke my heart.”

“I don’t rely on irony. My artwork is not sardonic that way; it just isn’t,” she explained. “There will be one site focused on a real sense of loss, and it will be Celilo.”

At Celilo Park, where we were headed, a sense of loss was inescapable. An unimpressive expanse of grass on the south bank of the Columbia River 16 miles east of The Dalles, the stretch of river had for millennia been the region’s most important fishing and trading center, as well as a sacred place where religious ceremonies had been held. The mighty falls that once thundered there had been inundated by the Dalles Dam in the middle of the last century, an event generally regarded as a final death knell for the native tribes’ salmon-based economy, if not for their culture itself. Fifty years later, the wounds were still raw. In a few hours, spiritual and political leaders from various tribes would bless the future Confluence Project site, and Lin hoped to glean clues from the ceremony about how to proceed.

It seemed an apt moment to broach the topic of memorials in general, a topic I’d so far carefully avoided, knowing Lin’s distaste for it. Celilo, it seemed, opened a door to discussing the larger subject of architecture and public mourning. I told Lin that in light of the distinction she drew between memorials and memory works, I’d like to ask her about her service on the competition jury for the World Trade Center memorial.

Lin marks a spot for a story circle, a ring of metal, stone or concrete that will be inscribed with information about the Columbia Plateau tribes.

Predictably, she asked that the interview be curtailed.

However, after a tense few moments during which she delivered a lament about the tragedies of being typecast as a monument maker, she allowed the conversation to proceed.

Because the country had rushed to memorialize the attacks on the World Trade Center, some people had argued that a neutral design such as Arad and Walker’s, one that could be imbued with various meanings, was the only possible response, I said.

“This is the thing we’ll never know,” Lin replied, interrupting me. “They moved very quickly. And I think when you’re in the throes of grief, you’re going to reach and grasp and move fast, thinking that’s going to make you feel better. But in a way, only time is going to make you overcome it. I think there’s this false expectation laid down on memorials, because of the success of the Vietnam memorial, that you’re going to feel so much better from it. And that’s a false hope.”

Her comment shed an interesting light on the memorial at Celilo. The similarities between the drowned falls and the felled towers were considerable, after all. Both the World Trade Center and Celilo Falls had previously been potent symbols of national identity; both had been powerful centers of trade and cultural interchange; both had been destroyed in cataclysmic inversions of vertical space (the towers having fallen, the waters having risen); and in both cases, the memorials would commemorate the loss on the actual ground where the loss had occurred.

But the differences were just as remarkable. On Sept 11, nearly 3,000 people had been killed and an icon of American capitalism destroyed by foreign attackers. In March 1957 an international cathedral-cum-agora had undergone a scheduled demolition by domestic colonizers. One event represented a threat to a way of life; the other represented a culture’s near-extinction. And strangely, where Arad and Walker’s design had been embraced by a public eager to assuage its grief, Lin’s had been met with doubt. Her first proposal—to excavate the riverbank and erect a glass wall that would peer into the watery wreckage of the falls (in an eerie echo of Arad and Walker’s scheme)—had been dismissed by tribal members who perceived it as tantamount to digging up their mother’s grave. Some had suggested that the tragedy should not be memorialized for seven generations.

What did this mean? It was one of many important questions the Confluence Project raised. In a world where people’s histories, languages and philosophical beliefs are so disparate, is there such a thing as a shared architecture of memory? When a trauma is so deep that it has already obliterated memory, is it possible to commemorate it at all? Can public art hope to rebuild the collective memory where politics has failed?

Unfortunately, these were not the questions I had chosen to ask. And without much further ado, Lin, evidently fatigued and distressed by my interest in the memorial underway in Manhattan, informed me that now the interview really was over.

Two months ago, in September, Lin released a conceptual plan for her artwork at Celilo Park. It will consist of a 300-foot walkway arcing across the grass, its terminal point cantilevering over the water. Like the black granite in the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the water beneath the walkway will glisten, reflecting its surroundings rather than exposing what lies underneath. Still, fragments of text will invoke the history of the falls from the time of their geologic formation to the present; the words at the river’s edge will describe the crashing sound the waters had once made before they were forever muted.

But on March 18, Lin didn’t know what would happen as she stood on a patch of lawn between the river and an expansive parking lot, with about 200 people—some Indian, many white—who gathered to observe the Celilo blessing ceremony. Lewis Malatare, a tribal elder of the Yakama Nation, was among the last to speak.

Malatare spoke of the many hardships his people—the Indian people in general—had endured. He warned of the endangered status of Indian cultures, and of the importance of continuing to keep oral histories alive, so that “generations yet unborn would know that this”—Celilo—“was such a beautiful, beautiful place to be.”

He spoke of being a veteran, and of visiting the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC, to pay respects to friends and relatives he had lost in the war. Of how, when he touched the smooth stone, “it became a part of me.”

“I hope,” he said, “that this memorial will have the same feeling that the memorial in Washington had.”

The stories of Celilo, the stories shared with children, would never change, he continued, his voice wobbling. “Through our words and our oral history, the mists, the noise, the sound of laughter will always be there.

“One day, we will receive, once again, Celilo. Because we did not give it up. We did not sell it.”

Col. O’Donovan, a distinguished-looking man in a brown uniform who represented the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, took the podium next.

“I’m proud to welcome you to Celilo Park,” he announced, “which belongs to the people of the United States, which we the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers hold in trust …”

Mercifully, his speech was short. Lin’s was even shorter.

“I am here because you asked me to be here,” she said, in a voice that seems always a bit thin on affect, but always, at the same time, persistent and clear. “I only hope I can do something here that doesn’t disappoint. I sense still a power under the water. And I sense a loss that can never truly be recovered. But I hope that I can put something here that can tell my children, your children, your children’s children, what is still there in memory, under the water.”

MEMORY MAP

By the time the Confluence Project is complete, seven major site-specific installations by artist Maya Lin will dot the Columbia River system from Washington’s eastern border to the Pacific Ocean. One installation, at Cape Disappointment State Park, and a second, at the Vancouver National Historic Reserve, have been complete since November 16, 2007.

See www.confluenceproject.org for additional details.

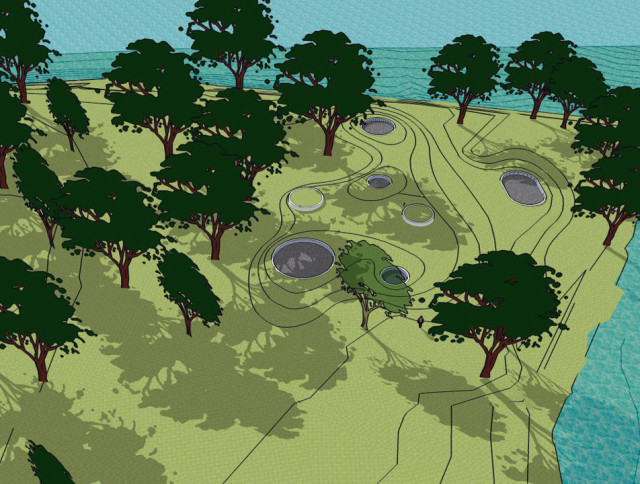

RIDGEFIELD NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Lin will design an environmental research center adjacent to an approximately 5,300-acre nature sanctuary near the confluence of the Columbia and Lewis Rivers—an area that once sustained large communities of tribal people where Lewis and Clark spent the night in 1806.

Scheduled completion date: TBD

Image: Jones & Jones Architects

VANCOUVER NATIONAL HISTORIC RESERVE

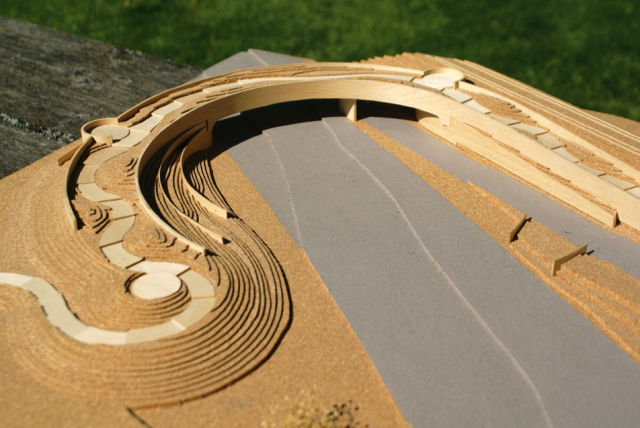

An earth-covered pedestrian land bridge, designed by Seattle-based landscape architect Johnpaul Jones in consultation with Lin, will cross State Route 14, reconnecting the former trading post and military fort in Vancouver, Wash., with the waterfront. An artwork by Lin represents a treaty table at the water’s edge.

Dedication: November 16, 2007

Image: Maya Lin Studio

SANDY RIVER DELTA

One of two projects on the Oregon side of the river [the other being Celilo], this site near Troutdale and the Sandy-Columbia confluence will feature a "bird blind," a structure walled in wood slats that will display the names of the animal species that the Corps of Discovery recorded.

Scheduled completion date: 2008

SACAJAWEA STATE PARK

Large rings, inscribed with text, will be set into the waterfront lawn of this park at the Snake-Columbia confluence in Wasco, Wash. These "story circles" will relate aspects of the history and culture of the Columbia Plateau tribes. Landscape restoration, a redesigned boat dock and a pathway to a viewpoint overlooking the Snake River will complete the artwork.

Scheduled completion date: 2009