Can a Lab Save Some of the Northwest's Precious Art?

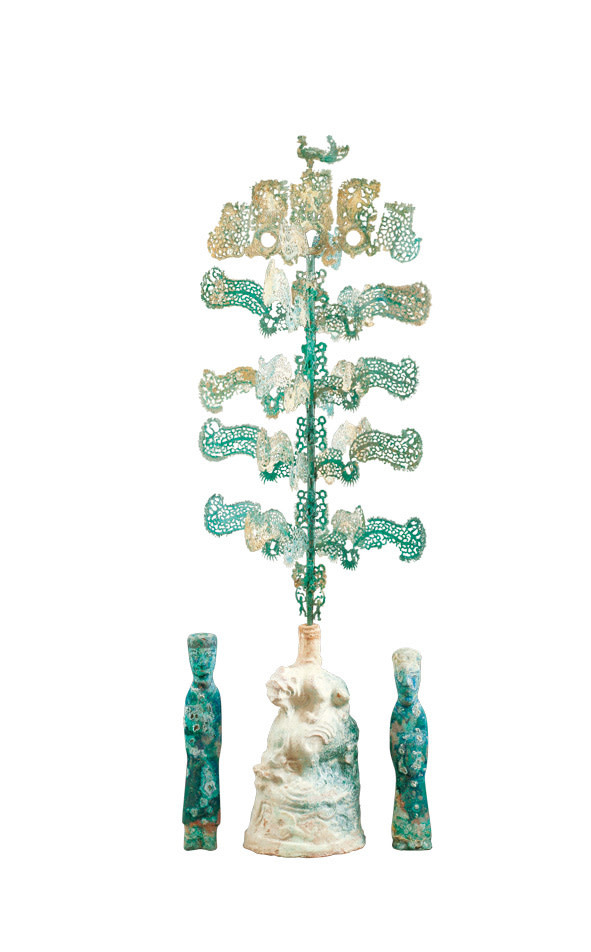

LAST FALL, as the maples, elms, and poplars outside the Portland Art Museum painted the paths along the South Park Blocks in vibrant reds and yellows, another kind of tree decided to lose its leaves. The museum’s two-thousand-year-old Chinese money tree—a rare burial sculpture made of bronze and clay—dropped two pieces from its intricately designed branches. A security guard discovered the delicate metal foliage at the bottom of the display case one October afternoon.

It was the third time in eleven years that a part of the work had broken off. The previous times, local freelance conservators had reattached the pieces. But when the leaves dropped a third time, curators knew they needed a deeper analysis of what was causing the deterioration. The nearest lab capable of doing this was in Los Angeles; sending the tree there could cost $10,000.

Instead, curators removed the tree from display until they could figure out what to do. Fortunately, a new Portlander was about to offer a solution. Chemistry professor Tami Lasseter Clare had moved to town in June from Philadelphia, where she’d pursued postdoctoral work in art conservation at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. When she learned that PAM has only one part-time papers and books conservator—freelancers work on sculptures—she figured she could help the museum, and create a learning opportunity for students, by establishing the PSU Laboratory for the Science of Art and Conservation. “There are tiny museums on the East Coast that have labs and conservators on-site,” she says. “That standard of care is absent in Portland.”

Clare’s lab would provide regional collections like PAM—which last year removed several pieces from display for cleaning and conservation work—with a resource for thorough scientific analysis. While conservators generally can touch up art, sometimes the genesis of ruin is more elusive: a rusted nail buried in a painting’s frame, for example, could cause the surface to crack or the pigment to decay. Scientists like Clare use techniques such as X-radiography and infrared microscopy to help identify a piece’s makeup (say, whether the artist used oil or acrylic paint) and potential sources of decay.

Right now, the lab consists only of Clare and two student assistants; by 2011, she hopes to raise $1.5 million from grants and private donors to fund a staff of five technicians and graduate students and to purchase lab equipment—like the $50,000 handheld X-ray fluorescence spectrometer that is currently on loan from a Washington optics company.

“This is a new model for a science laboratory—being a regional lab and not being located within a museum,” she says. “It will give students the experience necessary to enter graduate programs in art conservation.” The lab has the potential to be more than just a body shop for art. PAM’s director of collections management, Donald Urquhart, is already salivating over the idea of having Clare X-ray the museum’s Van Gogh painting, The Ox Cart, to find out more about the kind of paint used.

But first, the money tree. It waits in the museum vault as Clare completes her tests on the cause of its defoliation. She expects results by the end of this month. And she hopes to have the priceless work back on display, fully intact, by fall, just as its living counterparts out front begin once again to shed their leaves.