Jump Start

FORTY THANKSGIVINGS ago—when gas cost 36 cents a gallon and airline security meant putting on your seatbelt—a polite, nondescript man showed up at Portland International Airport. He paid cash for a Northwest Orient ticket to Seattle, giving the name “Dan Cooper.”

As the plane sailed through the stormy Northwest night, the man told a flight attendant he had a bomb. He demanded $200,000 and four parachutes. (He also politely insisted that she keep the change after he paid for his two bourbons and soda.) In Seattle he swapped passengers for his money and ’chutes, and the plane took off, ostensibly for Mexico City. Somewhere over southwest Washington, the hijacker lowered the plane’s aft staircase, strapped on a parachute and 21 pounds of cash, and disappeared into the drizzle.

Despite one of the biggest manhunts in Northwest history—and odd scraps of evidence surfacing over the years—no one knows what happened after he jumped. And hopefully, no one ever will.

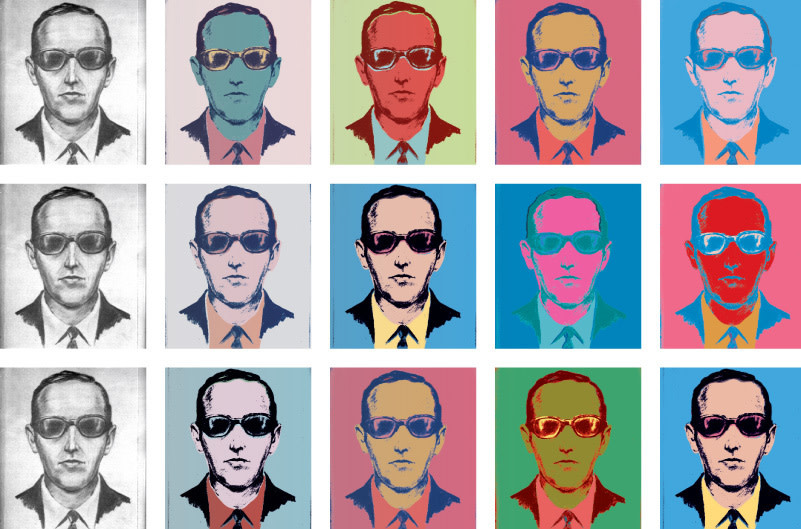

A reporter mistakenly dubbed the vanished outlaw “D. B. Cooper,” a name that forever attached itself to eerily vacant artists’ sketches. The suave bandit’s exploit remains the only unsolved American airline hijacking, the subject of a still-active FBI case file that could fill a small-town library. And from the very beginning, people seemed to hope the mystery would never resolve.

Cooper remains a subject of fascination throughout the Northwest, where stray clues have surfaced over the ensuing decades. A hunter found a piece of the plane’s staircase seven years after the incident. Then $5,800 turned up in a Columbia sandbar near Vancouver in 1980. Meanwhile, the list of suspects has included army paratroopers, talk show hosts, and a transsexual pilot. Leads still percolate: this summer a woman went on CNN claiming her long-dead uncle, buried near Bend, was the hijacker, based on a conversation she overheard when she was 8. (The FBI soon shot down her claim.) In September, the flight attendant who spent the most time with Cooper turned up near Eugene, where she had spent the better part of her post-hijack life in a Catholic nunnery.

While a good mystery’s allure is universal, the Cooper legend seems perfectly suited to the loamy soil of Northwest folklore. Despite (or maybe because of) its prim reputation as America’s home of composting-based lifestyles, the region treasures connections to a more roguish past. Portland, in particular, nurtures whole mythologies connected to highly dubious stories of Shanghai tunnels. Generations of local yarn spinners, from Stewart Holbrook to Phil Stanford, have milked tales, in some cases at least semi-tall, of the town’s bygone skullduggery.

“We don’t revisit the Cooper story just because it’s interesting—we find some meaning in it,” says folklorist Casey Schmitt, whose University of Oregon master’s thesis examined the wilder edges of Northwest oral tradition. “It’s a kind of cathartic rebellion.” Cooper disappeared into our craggy wilderness and deep forests, just like another famous local legend, Sasquatch. The shy, hirsute beast and D. B. Cooper have a lot in common, actually: an aversion to cameras, a tendency to frighten but not harm, and the promise of fame to whoever finally tracks them down.

For today’s Portland, Cooper’s mix of civility and criminality embodies our perpetually endangered weirdness. His caper also strokes our retro fetish for the days when flirty “stews” wore go-go boots, pilots stashed Playboy in the cockpit, and $200,000 (just over $1 million in today’s currency) was worth “skyjacking” for. His complete disappearance likewise marks him as a relic of an extinct age. Today, security cameras, tagged Facebook photos, and swiped transactions make that degree of oblivion almost enviable.

Modern outlaws rarely win a place in myth—our 24-hour news culture digests them too quickly. (Does anyone remember the “Barefoot Bandit,” the serial thief from Washington who heisted boats, bikes, and planes before his capture just a year ago?) In an oversaturated era, Cooper seems refreshingly untouchable. “As a culture, there’s a need for us for him to get away,” says Geoffrey Gray, author of the recent book SKYJACK: The Hunt for D. B. Cooper. “He represents something more to us than just a guy who jumped out of a plane.”

Maybe that’s why Cooper still shows up on T-shirts and trading cards, in Kid Rock songs, and as a character in Portland’s Rose Parade. As the economy stumbles, the government fumbles, and Wall Street laughs all the way to the bank, Cooper remains a quixotic vision of a lonely gamble against fate.

“Not everyone gets a chance to do that, but a lot of people would like to,” says folklorist Schmitt. “Everyone feels like the little guy sometimes.” And, Schmitt adds, an open ending means anything can happen: “As soon as he jumps out of the plane, that story can go anywhere.”