Dark Star

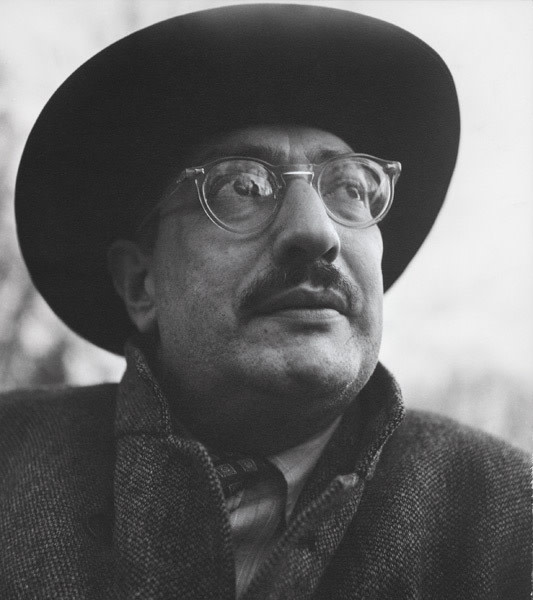

Photo: Courtesy Portland Art Museum.

Mark Rothko c. 1950

AFTER WEEKS TRAVELING from the Baltic Sea on the steamer SS Czar and from New York City on a train, a boy who would become one of most America’s most revolutionary artists arrived at Portland’s Union Station in September 1913. Then known as Marcus Rothkowitz, the 10-year-old spoke Russian, and probably some Yiddish. He, along with two brothers and a sister, joined the bustling immigrant community of Jews and Italians south of what is today SW Market Street.

Decades later (and far from Portland), the erstwhile favorite son would join with a small cluster of painters dubbed the “New York School” to pioneer bold, new forms of abstract painting. With his name shortened to Mark Rothko, he would defy the very notion of a “painting” with earthy fields of atmospheric color and embody the volatile unease of an age of heroically tormented artists (Jackson Pollock was a contemporary) before ending his own life in 1970 with barbituates and slashes through arteries on both arms.

On February 18, the Portland Art Museum will open the first-ever local exhibition of Rothko—at least the Rothko now known throughout the world. (PAM actually hosted his first one-person show in 1933, when he was still Rothkowitz and was painting more traditional pictures.) Chief curator Bruce Guenther has assembled a 45-picture, dot-connecting look at the famed painter, from a Cezannesque 1926 still life and a 1932 portrait of his mother to his early-’40s experiments with surrealism to the ’50s and ’60s explorations of color and perception that won him his final place in history.

The retrospective offers Portland a rare chance to contemplate a luminous talent, at once homegrown and problematic for a city that loves to stake its parochial claim on every creative talent who passes through. (See: John Reed, Minor White.) “Will you find a sun rising behind Mount Hood in his layering of color?” snorts Guenther. “I don’t think so.” Some paintings and drawings of Portland exist, but Guenther chose not to venture that deep into the archives, rather borrowing from the National Gallery, top Seattle collectors, and Rothko’s daughter and son, the latter of whom—hint, hint—might be so generous as to leave one or two paintings behind.

Several pieces in the exhibition easily stand among the most valuable 20th-century works ever to be shown in the city. Small wonder why. As Guenther wryly points out, a Rothko—in poster form—“has lived on every dorm room wall.” He is a male equivalent of Georgia O’Keeffe for how seductively his color fields radiate when reduced in reproduction. Though critics were mixed on his work at the time of its making (Clement Greenberg dismissed him as “indebted” to contemporaries like Clyfford Still), to see Rothko’s paintings now is to discover another in a long lineage of old masters. Look closely at his misty fields and glowing bands of pigment (or even his late, gray work), and the brushstrokes defining each square inch can rival those of Rembrandt or Turner.

Photo: Courtesy Portland Art Museum

Mark Rothko, self-portrait, 1936

In conjunction with the PAM show, other local arts organizations will help flesh out this intricate aesthetic and personal legacy: Portland Center Stage will present the bio-drama Red, based on Rothko’s epic struggle with a commission for the Four Seasons Restaurant, and Third Angle Ensemble will play “Rothko’s Chapel,” composer Morton Feldman’s ode to the artist’s church–cum–artistic shrine in Houston.

For all his global importance, Rothko’s short, early stay in the fertile, socially tense milieu of early-20th-century Portland can hardly be dismissed. In the war against authority, convention, and interpretation that Rothko waged all his life, the earliest battles were fought here. Around the time his family arrived, Portland’s Jewish population was in the process of more than doubling. In the tight confines of the South Portland neighborhood alone, there were four synagogues. Portland had already had three Jewish mayors. The city teemed with successful Jewish merchants, from the furniture dealer Isaac Gevurtz to Julius Meier, heir to the department store that anchored the city’s shining white terra-cotta district.

But Rothko began life in Portland as an underdog, a state of mind that would animate his early politics, his deep insecurities and outsize ego, and his restless pursuit of ever-more narrow definitions of success. His family was poor, part of a wave of Eastern European Jews fleeing the rising anti-Semitism of czarist Russia. Only months after arriving, his father died of colon cancer. Rothko learned English by ear in elementary school before attending the original Lincoln High (today the Portland State University performing arts venue Lincoln Hall). He recalled hearing Emma Goldman speak in 1915 on anarchism, free love, and birth control (the last topic netting her a fine of $100). As in many US cities, the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 stoked both labor unrest and fears of “reds.” (That year, labor rabble-rouser and one-time socialist William Daly nearly became Portland’s mayor.)

As a junior at Lincoln, Rothko cofounded a debate club and a column in the Cardinal, “an open forum for ideas.” Both were, at least in part, a response to Jews’ exclusion from the school’s social clubs. This writing and organizing presaged later actions and manifestos that helped articulate an intellectual and revolutionary spirit for the new American painting. Though Rothko was sharp enough to graduate from Lincoln early with a scholarship to Yale, his WASP classmates nevertheless chided his heritage in the yearbook, scrawling that he mostly likely was destined to become “a Pawn Broker.”

Rothko claimed he was self-taught, but the Portland artistic atmosphere was plenty fertile. The innovative Portland Art Museum director Anna Belle Crocker initiated art education programs at Lincoln, bringing the students into the museum for talks and tours and showing reproductions in the school’s hallways. During an after-school job, an employer recalled, Rothko frequently whiled away time sketching on wrapping paper.

Rothko left Yale after two years, returning to Portland where, among other things, he acted (once, he later bragged, with Clark Gable as “an understudy” during that actor’s brief sojourn here). After moving to New York for good, he occasionally came back. Camping in Washington Park on one visit, he and his first wife, family members recall, were rousted by police for public nudity.

Had he stayed in Portland, Rothko once said, he “would have been a bum.” Indeed, whatever imprint Portland left on him is hard to detect. His childhood haunts were scrapped in early-’60s urban renewal. His paintings are nothing if not ineffable. Stare long enough at a Rothko abstraction and you might very well see the sunlit mists engulfing Hood—or, just as easily, the uncertain promise looming beyond your own emotional cliff. Rothko once described his paintings as “dramas” in which the shapes were “performers.” Successful art, to him, had a dimension he often described as “tragic.” For all of the serenity often ascribed to his paintings, the artist himself believed his works “imprisoned the most utter violence in every inch of their surface.”

Provocateur, libertine, revolutionary, and, as many an acquaintance described him, simply “lonely,” Mark Rothko embodied many roles. But the earliest was the ill-fitting émigré on the stage of South Portland.