Riffing on the Bard

One-time ballerina Anne Mueller retakes the stage in a Kabuki-toned version of Titus Andronicus.

Image: Casey Campbell

ANNE MUELLER SHIVERS under her kimono on a cold, blustery late-spring day in Hills-boro’s civic plaza, lilies woven into her light-brown hair, her sharp features looking like porcelain under their coat of white makeup. A male voice asks her to mimic a sakura tree. The retired Oregon Ballet Theatre dancer obliges, twisting her lean body into a sturdy trunk, limbs reaching outward. As several curious families stop to watch the action slowly unfold in the first costume test for a production of Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, the only clues that Mueller is playing the freshly maimed character of Lavinia are the dark holes in the sleeves where hands should be and the red smear signaling her character’s tongueless mouth.

The families might pause before coming back. For even hard-core Shakespeare aficionados, Titus can be tough to watch. The Bard’s first—and grisliest—tragedy is often discounted as a young playwright’s desperate effort to break out in the late 1500s, when blood and sex were as popular with theatergoers as slasher movies are today. But the man excitedly coaching Mueller, Scott Palmer of Hillsboro’s Bag & Baggage Productions, thinks it’s the perfect “lite” summer fare to bring to life in the western suburb’s public square.

“There’s something hysterical and beautiful and terrible about Titus,” says Hillsboro native Palmer, a towering man with a bit of salt peppering his hair and a tendency to talk in exclamation points. “I also know that not everyone shares that opinion, so (I’m) trying to find that vehicle that would enable me to get across that combination of horror and beauty.”

And so Palmer infused Titus’s macabre brew of blood, tears, depravity, rape, murder, and cannibalism with the elegance of Mueller and the fierce beauty of Kabuki in the costuming, makeup, movement, and music, down to the original score performed by a six-piece ensemble fronted by a koto player.

Palmer’s Kabuki Titus is merely the latest production by a seven-year-old troupe gaining notoriety for innovation, daring, and craftsmanship to match any Portland theater. Its original twists on Shakespeare have included an all-male Romeo and Juliet that recast R&J’s forbidden love as an allegory of modern homophobia. The company unearthed a take on The Tempest by Shakespeare admirer John Dryden (never before performed in the States), presenting it as a glam-rock farce. The group has also riffed on contemporary classics such as The Glass Menagerie and Crimes of the Heart and presented adults-only Christmas shows like The Eight: Reindeer Monologues.

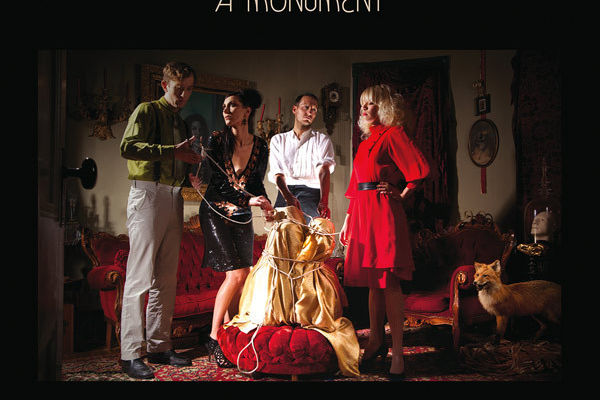

Director Scott Palmer (front) transformed a roving group of vaudevillians into a resident theater for Hillsboro — and an experimental force for the region.

Image: Casey Campbell

Behind the curtain of B&B’s playful tinkering and remodeling is the steady mind of a serious student of theater, particularly of Shakespeare. Palmer, 43, earned his undergrad degree in theater and philosophy from the University of Oregon and his master’s in speech communications and theater from Oregon State. He went on to pursue a doctorate in Scotland before quitting to cofound the Glasgow Repertory Company. He returned to his hometown in 2005 to form a traveling regional theater troupe that, much like the company in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, wandered from small town to small town to perform the classics with props and costumes in tow (hence the name Bag & Baggage). But thanks to the support of the City of Hillsboro and a local developer, Palmer’s vaudevillians evolved into the resident company for the renovated 380-seat Venetian Theatre.

Palmer first conceived Kabuki Titus in Glasgow a decade ago for a group of visiting Japanese dignitaries as a stripped-down, 30-minute one-off featuring three actors. But the idea never left his imagination. To Palmer, the form is a natural fit, with its highly stylized makeup (crimson streamers will cap severed limbs), samurai swordplay, and balletic movement—the perfect vehicle for Mueller to push the grace she’s honed all of her life into an uncharted new direction.

“There are aspects of this role that are daunting,” says Mueller, for whom Titus will be her nonballet stage debut. “Some of the roles I felt most successful in were roles that made me really vulnerable and exposed. Being pretty is one thing. Being funny is another. Being real and authentic and vulnerable is a deeper challenge.”

In his research for the play, Palmer scoured original source material the Bard himself plucked from (Shakespeare, he notes, was a cunning thief of his contemporaries), lifting a passage from Thomas Nash’s Christ’s Tears Over Jerusalem (1593) to punctuate the general’s sorrow over his daughter’s fate; cribbing lines from Thomas Kyd’s Spanish Tragedy (1592); and evolving the villainous Goth queen with character bits from Christopher Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta (1590).

“Every time I read Shakespeare,” says Palmer, “I want to know … where did this idea come from, who did he steal from, and did he miss anything?”

Palmer’s approach is earning cred even with traditionalists. “I am extraordinarily impressed with the innovative commitment that Bag & Baggage has made to adapting in new ways that will make us see the play differently than we did otherwise,” says Pacific University English professor Lorelle Browning, who spent her younger days performing with the likes of Sirs Patrick Stewart and Ben Kingsley. “I was reticent at first. Then I was stunned.”

That’s the charm of Palmer and Bag & Baggage: they are sneaky, confident, outspoken, skilled, and happy to rile, a combination Palmer believes Hillsboro is ready to accept and that Portlanders should come westward to experience in a place most center-city dwellers know only as “where Intel is.”

“The layers of diversity in this community are amazing,” Palmer says. “Pandering is never the answer. Our audiences would leave. Our people can smell that from a mile away.”