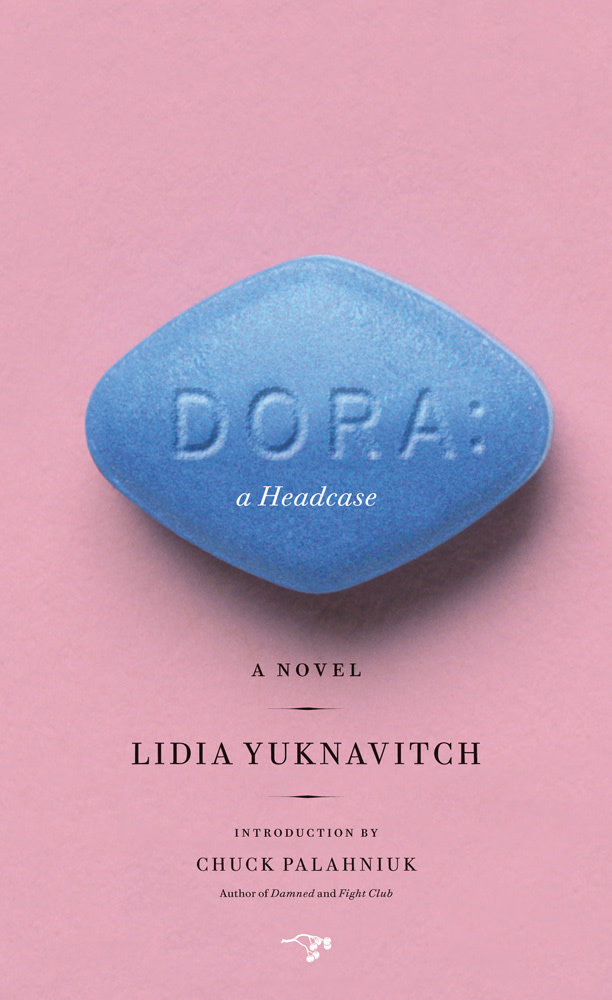

Review: Dora: A Headcase by Lidia Yuknavitch

From Heathers to Mean Girls to Gossip Girl, the scary teenage girl is a well-worn pop culture character—flippant, stubborn, and obnoxious. But in Oregon author Lidia Yuknavitch’s novel Dora: A Headcase, that familiar archetype becomes a razor-edged scalpel for dissecting what it means to be categorized, typed, and diagnosed.

Loosely based on Sigmund Freud’s famous case study about a girl with the same name, Yuknavitch’s Dora (real name: Ida) is the daughter of a philandering father and self-medicating mother. She is what polite society would deem “troubled”: she shaves her head, steals prescription meds, and generally gives the finger to what she thinks the world expects. When her father sends her to see Freud (whom she calls “the Sig”), he diagnoses her with that handy feminine catch-all: hysteria. So Dora hatches a plot to analyze him instead, turning the concept of therapy completely on its head. What follows is a down-the-rabbit-hole adventure riddled with heart, hate, and hilarious dark comedy, as we ride along with Dora and members of her eccentric self-proclaimed family, which includes a 282-pound gay pianist, a domestically abused Native American teen, and a beautiful trans person named Marlene.

Following in the misfit footsteps of her Portland literary forebears (see Katherine Dunn’s and Chuck Palahniuk’s protagonists), Dora is not an immediately relatable character. But likeability is not the point. Dora is an homage to surviving one’s youth, and to the difficult importance of being understood. “Next time you work with a female,” Dora imagines telling the Sig, “ask her which city her body is. Or ocean. Give her poetry books written by women. Let her draw or paint or sing a self before. You. Say. A. Word.”

Much as in The Chronology of Water, Yuknavitch’s Pacific Northwest Booksellers Association Award–winning memoir, the reader gets caught up not only in Dora’s very personal fight for survival, but also in Yuknavitch’s expert use of language. She writes with such visceral and erotic fluidity that the reader feels slightly intoxicated, wrapped up in what Yuknavitch calls “straight no chaser” narration.

In Dora: A Headcase, Yuknavitch turns the tables, examining the examiners through the eyes of a teenage girl. Try to tell me I’m broken, it says, and I will come at you with all of my brokenness.-