Rock Star

Sea Cave, Terminus of Cape Lookout 2000, Courtesy PDX Contemporary Art

"I’ll show you the first rock that changed my life," says Terry Toedtemeier, and retreats upstairs. The 59-year-old artist and photography curator for the Portland Art Museum and his wife, art historian Prudence Roberts, live in a renovated 1918 post office at the edge of Tideman Johnson Park in Southeast Portland, a cozy ramble of gradually accreted add-ons stuffed with art and books. When he reappears, he’s displaying a mineral lump about the size and shape of half a grapefruit, squeezed. Its skin is lumpy and mottled with hues of coral, white and gray.

"I’m a little kid, about that tall," explains the moony-faced, balding Toedtemeier, gesturing about waist-high. "I figure out that you can break a rock open by putting it under another rock and hitting that rock with a big rock." He rotates the lump to expose a sparkling nest of quartz. "It looks like that on the inside. I look at this, I look up at the sky, and I remember thinking, What is this stuff all about?" The crystalline structures represented an "organizing system" in the universe. "It wasn’t some old guy in a rock shop showing it to me. It had the authority of the world."

The early epiphany set the Portland native on an idiosyncratic quest: part scientific, part historiographic, part artistic, part spiritual. Since the 1970s the self-taught artist and photographic historian, whose highest academic degree is a bachelor of science in geology from Oregon State University, has trained his camera on catastrophic turns of geology–in particular a massive Miocene Era lava flood that deposited basalt over hundreds of square miles of this region. While Toedtemeier has crisscrossed the Columbia Plateau by plane, car and foot to probe the fundamental mysteries of existence immanent in these bizarre and beautiful rock forms ("I love going off-road: U.S. Geologic Survey maps are like popcorn. I take a big bag," he confesses), he has also pursued a second obsession: daylighting the darkened history of landscape photography in the West.

From a stack of photographs on his dining table, he lifts a reproduction of Cape Horn Near Celilo, an image recorded by pioneering photographer Carleton Watkins during his summerlong tour of the Columbia River Gorge in 1867. Watkins set his camera on the south bank of the river, looking east down the gorge. In the foreground is a huge outcropping of basalt; a railroad track curls around its base and off into the distance. At a time when few urban photography studios had equipment to produce negatives as large as 8-by-10 inches, Watkins, commissioned by the Oregon Steam Navigation Company, used mules to tote 18-by-22-inch glass plates and a camera big enough to accommodate them through roadless areas. Through this synthesis of economic forces and creative will, the Oneonta, NY-born entrepreneur became one of the inventors of modern landscape photography, Toedtemeier explains, presaging movements of the mid-20th century with his frank, deftly composed depictions of the countryside. In the process, he confronted the same artifacts of geologic history that were to captivate Toedtemeier.

"I had a real visceral reaction. They made complete sense to me," says Toedtemeier, who first learned of Watkins while volunteering in the Oregon Historical Society’s photo archive three decades ago. Fascinated, he drove to the Oregon State Archives to view a rare, 35-image album of his Oregon pictures. "There are lots of beautiful photographs, but there are some like meditation bells: You could listen to them ring for a long time."

{page break}

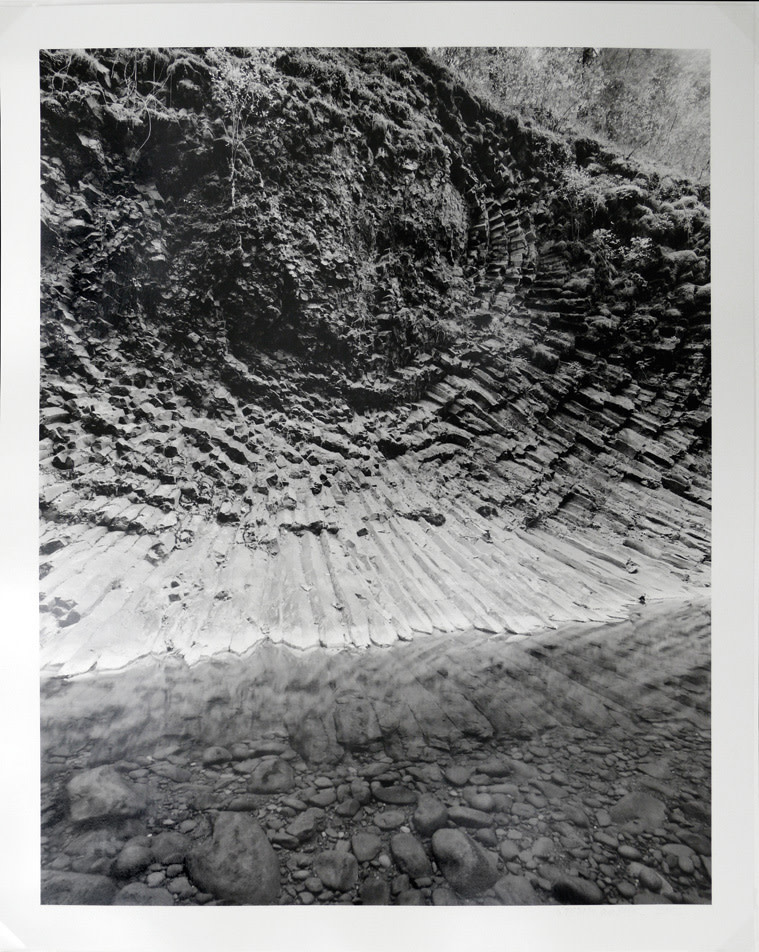

Radical Fractures, Basalt, Mollala River, Clackamas County, Oregon 2002, Courtesy Portland Art Museum

He offers for inspection one of his own images, a breathtaking shot of the Haystack Rock near Pacific City, taken from the air. The black monument emerges like the back of a sea monster from the roiling silver water. "I’ve taken a lot of photographs of that rock. As a kid I used to take a fishing boat out there," he explains. Years later, he learned that the basalt headlands of Oregon’s northern coast were probably the fingertips of mantle plumes, extraordinarily rare upwellings of hot rock from the earth’s mantle that produced rock formations stretching from Steens Mountain to the coast. In the mid-’90s, piloted by his friend Herb Hill in a Piper Pacer, a World War II-era light plane, he started taking his 4-by-5 camera aloft to better capture the massive contours of these forms. "I can take the door off the side and just sit there, looking down," he says.

After all, truth and beauty are matters of perspective. Watkins was a minor speck in the photographic canon in 1977, when Toedtemeier submitted a proposal to the National Endowment for the Arts to research his work and that of various of his 19th-century peers. Two years later an album of his photographs–much like the one owned by the Oregon State Archives, but containing 16 more images–was purchased at auction by a consortium of dealers for $101,000, a record for work by a 19th-century photographer. Today that State Archives album, gifted in the 1950s by the California Society of Pioneers for $4.90 in postage, is on loan to the Portland Art Museum and worth at least $3.5 million.

And Toedtemeier is again attempting to reframe history. "Time and again, geologists have been wrong out here. It’s analogous to what’s happened here in art history. Carleton Watkins made some of the best flat-out photographs of the 19th century. We all look somewhere else for something great," he says. "Well, it’s right here." Since about 2003, he and John Laursen, a local book editor and designer, have been raising funds to produce a six-part series of books on the history of photography in the Northwest. The first, Wild Beauty: Photographs of the Columbia River: 1867 to 1957, slated to be published by Oregon State University Press this fall, will contain works by Watkins and others who followed in his riverine wake, concluding with Alfred A. Monner’s depictions of the drowning of Celilo Falls. The final book in the series will feature Toedtemeier’s coastal photographs.

The volume may bring wider recognition to the venerable curator’s own, remarkable oeuvre. Meanwhile, it seems, a self-reappraisal is underway. "If you showed my sea caves to a Freudian or a Jungian, they’d tell you it’s not about geology. It really is Courbet’s Origin of the World," Toedtemeier says with a giddy laugh. The reference to the scandalous 1866 painting–depicting a woman’s lower torso and spread legs, peeking out from tousled bed sheets–is apt; it was painted seven years after Darwin published The Origin of Species and the year before Watkins made his tour of Oregon, a time when old beliefs about the world were being inundated by new ones. "We are part of the landscape."