Review: White Bird’s MOMIX

All photos courtesy White Bird.

One of the most magical moments in Momix’s Botanica performance that opened last night at the Newmark was one of its simplest. A dancer entered wearing what can only be described as a beaded lampshade on her head, where the strands of beads hung almost to her feet, like she had wrapped herself in those seventies beaded door hangings. But immediately she began twirling, and the strands shot out around her, spinning with such centrifugal force that they transformed into a shimmering halo that she deftly manipulated to rise and fall, whipping up and down and changing its plane. For minutes she spun, an ecstatic whirling dervish of modern dance.

MOMIX

Feb 27–Mar 2

Newmark Theatre

White Bird Dance

Momix bills itself as an “illusionist” dance company, and indeed the company explores and transforms the forms of its 10 dancers with every piece, using fantastical puppetry, costumes, and lighting. Founded by artistic director Moses Pendleton, the company’s method grows from his years with the legendary dance troupe Pilobolus and (one would guess) that company’s inception in the psychedelic early seventies. Pendleton was raised on a dairy farm in Vermont and later gained acclaim for the giant sunflower garden he planted at his home in Connecticut, and his inspiration from the natural, phenomenal world shapes every aspect of Botanica, from the animal sounds in the sound track to the projections of plants and flowers. But his artistic visions as a choreographer would fall flat without a cast of technically skilled dancers.

Momix brings Botanica to life through pleasing modern lines, fluidity of movement, and moments of great power and athletic strength. One female dancer appeared atop a mirror that sloped toward the audience, her body, adorned only by strong light and shadow, so perfectly reflected in it that there appeared to be two identical dancers joined together at the center, creating something far more abstract: a dancing Rorschach print.

Yet in the majority of the evening’s works, the choreography was not your typical modern company’s expression of an emotion or philosophical concept. These performers smiled and laughed, grimaced and yelled, giving up all inhibition and fully committing to their characters. A man walking around stage pecking his head, elbows jerking and wrists on hips like a strutting rooster, would look pretty silly if he didn’t totally lose himself in the absurdity of it all. The audience must be equally willing to give themselves up to the illusion. Although at times, it goes overboard, particularly in a number where the men are dancing bees—a wonderful idea that bees actually dance to communicate—but the dancers so over exaggerate their silent screams and gnashing teeth that it feels more like satire.

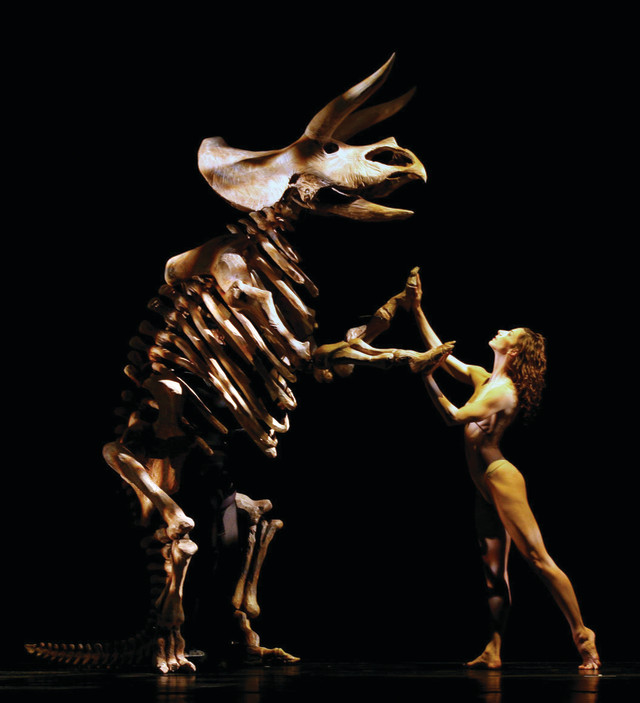

The company’s secret weapon comes in the form of puppets by the Scappoose, Washington–based puppet master Michael Curry. His skeleton triceratops is every bit as impressive as the horses in the touring Broadway production of War Horse. With only one person operating it, it walks, opens and closes its mouth, curls its tail, and carries a woman on its back. Curry, whose talents have been lent to everything from the Olympic Opening Ceremonies and Superbowl to the Lion King, also contributed two breathtaking structures of wood swathed in silky white fabric to the evening’s works. Both pieces were controlled by dancers but took on a life of their own, appearing to breathe as they swept across the floor, at times growing to the full height and width of the stage, and evoking a sense of eerie all knowingness.

Unfortunately, the sound design and projections were so distracting at times that they sabotaged the beauty of the pieces. Interweaving sound bytes from the natural world, Pendleton’s musical score traveled from Peter Gabriel’s “The Heat” to the female Irish ensemble Celtic Woman, but dwelled far too firmly in the New Age sound of the 90s. The projections, also by Pendleton, tended towards screen-saver style photos of flowers and plants that added an ugh-worthy literalness to pieces that would otherwise be beautiful with simple, evocative lighting. Both had the unfortunate effect of adding a dated quality to the show.

Nonetheless, there were moments of definite and exquisite beauty that created an exciting, even mystical world. It’s an experience not to be passed up.