Q&A: Cult Star Mink Stole on Working with John Waters and Divine

The original Dreamlanders cast and crew of 'Pink Flamingos.' From left: Divine, Mary Vivian Pearce, Mink Stole, Channing Wilroy, John Waters, Edith Massey, David Lochary.

As Waters’ crew continued to shock by playfully portraying rape, murder, abortion, and seemingly every form of filth and debauchery ever imagined (and then some), Waters won nicknames like the Pope of Trash, Prince of Puke, and Sultan of Sleaze, and the bigger-than-life Divine (seriously, 300 pounds), who was Waters idyllic cross of Jayne Mansfield and the clown from Howdy Doody, went on to a global stage as a disco singer. But just as their cinematic work began to flirt with mainstream success in 1988 with Hairspray, Divine died suddenly from a heart attack.

Along with his pencil thin mustache, Waters’ has two trademarks that all of his features share: they’re all filmed in Baltimore, and they all cast actress Mink Stole. One of the original Dreamlanders, Stole has played leading roles (Desperate Living), Divine’s various nemeses (Pink Flamingos, Female Troubles), and myriad other parts as Waters’ film grew slightly more glossy and palatable (Cry-Baby, Serial Mom, Cecil B. Demented, and A Dirty Shame). And with a lengthy resume beyond Waters’ outrageous oeuvre, Stole has become an indie icon of her own.

We’re excited to announce that QDoc, Portland’s queer documentary festival, opens on May 16 with the first doc to tell Divine’s larger-than-life story, I AM DIVINE. Stole will be in the audience seeing the film for the first time and will stay for a Q&A, along with director Jeffrey Schwarz.

QDoc will announce the full schedule and put tickets on sale shortly. [Ed. note: the program and tickets are now up].

In utter anticipation, we caught up with Stole by phone to talk about the early days, what it was like to work with Divine, the one thing she wasn’t willing to do on film, and moving back to Baltimore after many years away.

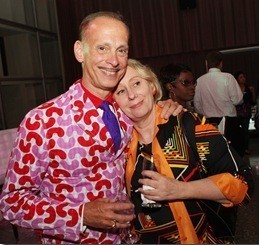

John Waters and Mink Stole

Mink Stole: We’re having our first day of hot weather today. It’s going to be 90. There’s a cardinal out my window right now. I love where I live.

Culturephile: You live on the street you grew up, right? What was it like to move back to Baltimore after all your films and their notoriety?

When I was feeling like it was time to make the big move out of LA and thinking, where would I go, the only place that made any sense was Baltimore. My mom was getting very old and only lived two months once I got here. Had I not come back, I would’ve missed her.

What’s it like to walk the streets where you all made your films now, 40 years later?

It’s all incorporated into who I am. I don’t think of it as ‘History,’ but as history with a small h, personal history. It is nice to go, ‘that’s where so-and-so lived,’ but as far as going to old movie sites, I would never do that. That’s like watching my own movies in the dark.

John still has a house there, right? Do you see him much?

Yes, his main office and house are here. We had dinner last week. When we go out to dinner, people ignore me completely, but he is so famous, it never fails to happen that people will stop him. They’re always nice, but it can be difficult to enjoy an evening alone with him.

How did you two first meet?

We didn’t meet until he was 20 and I was 18. We were both in Provincetown. We met at the beginning of summer, and by the end he and I and my sister and like four others were living together in this incredible place that was at the end of town that no longer exists.

We clicked right off the bat. There were lots of things that we had in common: Baltimore, a certain societal anger, a loathing for Catholicism. I hate the word ‘values’…

Those sound more like anti-values.

We had certain anti-values that were similar. I found John fascinating from the beginning. He was amazingly charismatic then, as he is now. He was smart and so well read; he was incredibly influential to me.

What about Divine? What’s your first memory of Divine?

At the end of the summer, we [John and I] both came back to Baltimore and moved back in with our respective families. We used to get together periodically on weekends and all take LSD and have great parties. I met Divine at one of those parties.

So much was going on; my life was changing so drastically. The neighborhood I grew up in was very socially conservative: wraparound madras skirt, cardigans, and knee-highs. When I started wearing jeans and had my ears pierced, it was a huge social statement. I’m one of 10 kids, but I felt as big a misfit as anyone else, so when I met John and the other people, I was like, ‘oh my god, you’re weird too.’

So a bunch of outsiders together on LSD. What was it like to film those early movies? Did you know what you were getting into?

I had no idea. John called up and said, “I want you to do scene.” The first movie that I did was Roman Candles. It takes three 8 mm projectors and a tape recorder to show. It was very much influenced by Chelsea Girls, the Warhol film with triple projection. We showed it in a church basement, but people came and liked it. It was a very exciting thing to have going on in my life that had been very dull up to then.

The next movie was Mondo Trasho. That was Divine in a gold lame capri outfit. I’ve always loved watching Divine work and loved working with Divine. He was an amazing performer.

You say in the documentary that it required 100 percent commitment to be in John’s films. What did you mean?

You were expected to show up on time, camera ready, knowing your lines, prepared to do what you needed to do. We had a good time, we had a lot of laughs, but when the camera was rolling, we were working. Look at Pink Flamingos: it’s all done in master shots. The scenes are long with no cutaways. If you do a five-minute long scene, and someone blows their line four-and-a-half minutes in, the scene had to be started over. We were all aware of the budget we had—film was expensive—so none of us wanted to make John mad. John ran a very tight ship.

Mink Stole as Connie Marble in Pink Flamingos:

[The language in this video is not appropriate for all audiences]

Back to Divine. You said you loved working with him. What was it like?

He was a very generous actor. If he was having dialogue with me, he would look at me and not cheat to the camera. It made it easy to work with him, although I had to work very hard because he was so visually staggering. If I wasn’t strong, I wasn’t going to be seen at all.

Particularly in Pink Flamingoes, where the very plot was a fight over being the filthiest person alive, involving one-upmanship of the nastiest kind. All of you did some very wild, provocative, and even dangerous stuff—stuff that hasn’t really been topped—from a sexual encounter that involved a live chicken to Divine’s infamous consumption of dog poop. Was there ever anything that was too much for you?

John always asked. In Pink Flamingos, I agreed to set my hair on fire and didn’t fully realize what that meant. When the scene came closer, I started to panic. What he wanted was for me to sit in a chair and have dialogue and not notice when someone put a match to my hair and have someone standby with bucket of water. The people that would be doing it were not practiced stunt people; there were friends of ours. All I could think was: I’m going to be bald. I will have burned scars on my head, and it will hurt, and I’M NOT DOING IT! But I had told him I would, and he expected me to hold to my agreement.

In retrospect, if it hadn’t worked the first time, there wouldn’t be a second time, and there I would be bald and nobody would remember it anyway, because what people remember about Pink Flamingos is that Divine eats dog shit at the end of it. I never regretted not doing it.

You’ve said before that John was a one-man band, handling every aspect of production, including picking everybody up in a van. What did you tell your parents you were doing when he would come get you for shoots?

My dad was no longer living. My mother was mortified—absolutely mortified. She had come to see the first movie, Roman Candles, and in one of the scenes a woman is dressed as a nun in full makeup smoking and drinking a beer and making out with a priest. My mother was a devout Catholic, and she didn’t come to another film until Polyester. Which was fine—I didn’t need her seeing me f**king someone’s toes in Pink Flamingos.

Throughout all of this time, she always adored John. It was so hard for her because she didn’t want to like him, but she was charmed. I would get ready to go, and she’d just look at me and sigh. She really, truly hated it, until the world at large started talking about John being a genius, and the city of Baltimore started making a big fuss, and then my mom wanted to go to all the premieres and parties. She changed. She’s an extra in Hairspray.

That’s amazing. Speaking of roles, what was your favorite?

Taffy Davenport [in Female Troubles]. I say that automatically because I relate to the misunderstood child. But I’ve loved every one. Peggy Gravel [in Desperate Living] was a wonderful character to play. She got to be so hateful. John always liked me hateful; he likes me to cuss and be mean and nasty.

So often in the films with Divine, I played the foil. I always knew in films with Divine that I was going to come out on the losing end.

The opening scene in Desperate Living with Stole as Peggy Gravel:

What is something people never ask about Divine but should?

He was good to his mom. I think people know that. One thing people do ask: did I call Divine ‘he’ or ‘she,’ and I always called Divine ‘he.’ Off camera he was male. He enjoyed very much playing men’s parts. My biggest regret is that he didn’t get to explore that more and become better known as an actual actor.

Where were you when you heard about his death?

I was home in New York. I lived right around the corner from Divine. I had just come home from the premiere of Hairspray in Baltimore. His mother was there, and it was the first premiere she had ever attended to my knowledge. He looked wonderful, so happy. A week later, I came home and there were a lot of phone messages, a lot of ‘call me’ messages, and then one from my mom that said, ‘I’m so sorry about Divine.” And I knew.

It was such a shock. I had just seen him—it can’t be true. Those of us who lived in New York stayed home together the next few days until we came down to Baltimore for the funeral.

What do you think his most enduring impact is?

I think it’s the triumph of the outsider—the triumph of the other. It’s that somebody who was picked on in school, who was perceived to be fat and effeminate, was able to take the negatives and transform them—with the help of John—into amazing positives that have had an enduring affect on so many people who have come after. I can’t tell you how many drag artists tell me they wouldn’t be who they are if not for Divine.

Divine had such a zest for life, such energy about him. He threw himself into whatever he was doing with total commitment and enthusiasm, and it shows. He took effeminacy and the desire to wear woman’s clothing into a whole other world that wasn’t about passing as a woman. It became a larger-than-life personality, and so drag becomes a cultural thing.

I totally think that for those people who feel they have no where and no one, for those people who live in places where being gay is still not okay, still villified, you can look at somebody like Divine and say, ‘this person made it big, and 25 years after his death people still care about him.’

Periodically I visit his grave, and there’s always a token of tribute that someone has left there. I find this to be so lovely, and who knew? I think Divine would be more than pleased to know that even after he’s gone, he’s very much alive.

Are you surprised that the movies you all made as kids have had such an incredible, enduring life?

We all knew we were going to do things other people found odd, but that was part of the fun of it. None of us, Divine included, expected while making these films that they’d have the life that they had and the importance they had in other people’s live. I didn’t anticipate that. I’m glad I didn’t, because I probably would’ve been insufferable if I thought people would care in 40 years.

You’ve been working on an album with your Wonderful Band for a couple years now, and I’ve read it’s almost done?

The recording is finished, the cover is with the designer, and after that it will get pressed and it will be available on Amazon and iTunes. It’s called Do Re MiNK. It’s almost three years in the making. I’m very happy with it. The first song on the album is my version of “Female Trouble” [the theme song to the 1974 movie that Divine sang].

QDoc

Bagdad Theater and the Kennedy School

May 16–19You’ve never been to Portland, right? What are you expecting?

I’ve watched Portlandia, which spoofs the hippie-dippy side. So I’m aware that it’s not as much a—what I’ve called an ‘earth shoe’ environment. So if there’s a Culturephile blog, there’s culture in Portland, but I’m totally unaware of it. I’m coming to Portland as a Portland virgin, but I have a feeling I’m going to feel very comfortable there.

Stole sings "Female Troubles" with SF drag performer Peaches Christ: