Dancer Linda Austin Reaches for 30

Image: Leah Nash

For the first dance Linda Austin ever choreographed, she went undercover. She snuck into a Sotheby’s art auction in New York to clandestinely record the murmurs of the audience, the bidding, and the slam of the gavel as works went up and down from the block.

The illicit recording became Austin’s soundtrack. A month later, she stood nervously offstage at New York’s Danspace Project, an international hub for contemporary dance, and watched her dancer Todd Ayoung irreverently “sneak” on stage in the dark—while wearing a headlamp—to set up music stands that displayed reproductions of famous works he tore out of a large volume titled something like Masterpieces of Art.

“I was watching from the doorway and was startled by the immediate laughter,” recalls Austin, who at 59 is reminiscent of a younger Patti Smith. “It gave me a frisson of excitement that carried me with anticipation out into the space.” As the Oregon native entered, she clicked a stopwatch and started one of the piece’s numerous small dances that she was, as she thought of it, auctioning off to viewers. She marveled not only at the nascent connection with the audience, but that she, a nondancer, was there at all.

Thirty years, hundreds of performances, and a still-fresh Rauschenberg Foundation SEED grant later, the now-veteran experimental dancemaker is revisiting that debut, called An Atrocity Exhibition in Two Parts. Ayoung, now an established artist in New York, will fly out for the piece, which Austin will combine with a new work in a double bill called Reach:30, June 27–30 at Performance Works Northwest. The steps will be new—she has no photos or video of the original—but the conceptual questions posed remain the still-relevant originals: How do we assign value to art? By turning experience into performance, do we devalue experience itself?

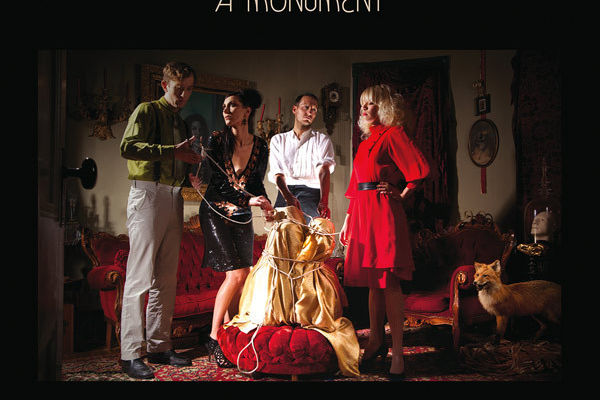

Clockwise from top left: The second piece Austin ever made, 1984’s “Recipe: A Reading Test,” “was one of those messy 1980s pieces where people got substances on their bodies,” she says; A solo dance called Scree at the legendary contemporary arts center Performance Space 122 in 1990; The last piece Austin made in New York before moving to Portland in 1998, Pig, involved wind-up toys and a field of eggshells crushed by the composer; A 1995 piece called “Trace” at PS122 in a short-works series called New Stuff.

Austin routinely dismantles the art of dance, strips it of artifice and exclusivity, and rebuilds it with improv, theatricality, multimedia, humor, and the occasional guerrilla tactic, taking cues from such movement modernists as Trisha Brown, Deborah Hay, and Merce Cunningham. Along the way, she has mentored a band of like-minded young performers. She isn’t so much rebelling against dance norms as searching for movement possibilities beyond them. In a career rarely known for fame or fortune, that pursuit, and its discoveries, has been her reward. “There’s something magical about seeing something created,” she says simply.

In 2008, Third Angle New Music Ensemble and four choreographers took over four public sites for The City Dance of Lawrence and Anna Halprin. Austin’s site was Lovejoy Fountain.

Image: Courtesy Jeff Forbes

How did a nice Medford girl turned Lewis & Clark theater major make her dance debut in one of New York’s most storied avant-garde scenes? The short answer is: accidentally. After graduating she moved east, planning to become a writer. But the lingering influence of a theater professor who liked the physicality of dance drew her to movement.

She had just started to dip her toe into the New York downtown dance scene when a friend mounted a show and invited people who had never made dances before to create work. “This dancing was about experiments in movement,” she says. “There was a playfulness. There were conceptual pieces—pieces with wild physicality.” At the time, Austin was reading a lot of art theory, thinking about how the art world created value, hence the surreptitious trip to Sotheby’s.

The dance world’s inclusivity was artistically liberating, if not lucrative. To support herself, she earned a master’s degree in teaching English as a second language, and she and five others pooled their money to buy a sixth-floor walkup for $48,000 in the then-dangerous Alphabet City section of the East Village.

Austin has called her Boris and Natasha Dancers “the greatest all-male non-dance dance troupe in the world.” Here, Scott Bricker, James Harrison, Peter Bragdon, David Bragdon, and Peter Ames Carlin perform at the Keller Auditorium in 2009.

Image: Courtesy Jeff Forbes

She spent nearly 15 years making and showing work at Performance Space 122 and other avant-garde venues, working with the likes of experimental theater pioneer Richard Foreman. But just as she began to feel she was dancing in place, she ran into lighting designer Jeff Forbes (whom she had met at Lewis & Clark) during an annual trip to Portland. They started dating. She began dreaming of having her own space. By then, the value of her apartment had nearly doubled. She cashed out her share, moved west, and bought an old Southeast Portland church in June of 2000, turning it into Performance Works Northwest. She and Forbes married there that October.

On the West Coast, Austin continued to develop her own style. Unlike many choreographers, she doesn’t start with music, but instead works with sound designers to create scores in tandem with the dance, such as last year’s A head of time, which was a meditation on mortality that interspersed documentary sound with songs like Chicago’s “If You Leave Me Now.” Nor is she interested in creating work that is merely decorative, when something deeper might be waiting just below the surface. “Prettiness is different from beauty,” she says. “Pretty is kind of standard. Beauty can be almost anything. A lot of things I see are small moments of beauty that other people don’t see.”

Austin’s most recent evening-length performance, A head of time, explored mortality and loss using multimedia and dozens of blankets.

Image: Courtesy Chelsea Petrakis

Beyond her own work, Austin has helped shape the wider local scene, turning her studio into a thriving hotbed of creation and community. She has re-created some of the events she enjoyed in New York, including the improv series Holy Goats and the Boris and Natasha Dancers, a recurring cabaret in which she stretches the democracy of dance by enlisting nondancers such as Deputy Secretary of State Barry Pack and Pink Martini bandleader Thomas Lauderdale. She also teaches workshops and rents the space to other performers at low rates.

“It’s an epicenter for an open kind of practice—people can be as experimental and as absurd as they want to be,” says local dance veteran Linda K. Johnson. “She’s so unpretentious and low-key and available. She’s genuinely always interested in what other people are doing.”

In too many cases, that interest has been her primary reward. While Performance Works Northwest tries to pay performers honorariums, she and Forbes donate their time. Last summer she announced PWNW was pulling back as a presenter and ending its decade-running Foreman Festival, citing exhaustion and the lack of financial support. But then she unexpectedly received a Rauschenberg Foundation SEED grant in November, awarding her $30,000 over the next three years.

“I had been wanting to focus more on making my own work,” she says. “The grant gives me freedom to do that but also to step up for other artists.” She has recently established an artist-in-residence program and is planning to pay people—and perhaps even herself, if only a modest stipend. After all, the question of how we assign value to art is still an open one.