Q&A: National Book Award–Winning Poet Mary Szybist

Courtesy Joni Kabana

Don’t let her gentle smile fool you—when it comes to poetry, Mary Szybist doesn’t skirt the messy, hard, complicated stuff. It’s where her poems live. And with her National Book Award win November 20th for her second book of poems, Incarnadine, it’s safe to bet she’s on to something.

The English professor at Lewis and Clark College spent ten years working on Incarnadine. Her previous collection of poems, Granted (2003), was a finalist for the National Book Critic Circle Award. And her win comes 50 years on the heels of Lewis and Clark's last National Book Award–winner, William Stafford. Might we have a new poet laureate on our hands?

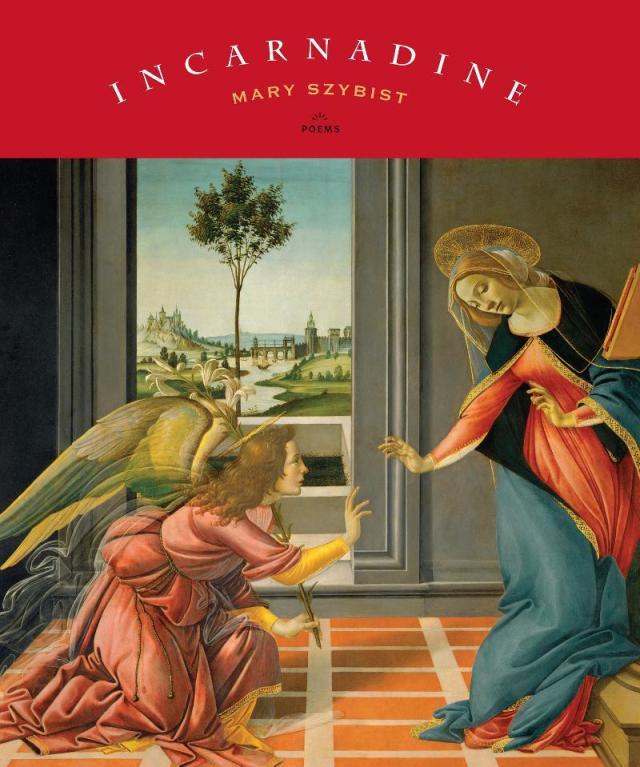

Haunting and vivid, chock full of wild interpretations and disparate images of the biblical Annunciation story, Incarnidine explores restless, complex feelings about faith, mortality, the carnal, and the divine. The Boston Globe's John Freeman wrote, “not since Adrienne Rich’s early work has a collection thought so deeply about the permeable barrier between the spirit and the body, and motherhood.”

In an interview after her win, Szybist told us what it was like to win arguably the biggest literary award for poetry in the States (where she ran into Portland's unofficial first lady, Carrie Brownstein), talks about why she never considered the book a feminist response to the biblical annunciation until now, and gave a peak at the next projects in the works.

On the Town: First off, congratulations on winning the National Book Award. What a momentous experience. What was it like, that moment of hearing your name announced and the ensuing events?

I was overwhelmed and stunned. I look back and I don’t know how I was able to muster the composure to walk up and accept the award and read what I had written given how dizzy and unnerved I felt. It was very unreal.

Other than the moment of receiving the award itself, do one or two things stand out from the events?

I was thrilled to meet the other writers, especially Frank Bidart and Lucie Brock-Broido, two poets I have read and greatly admired since I was an undergraduate. They were both warm and gracious and wonderful. It was also a thrill to meet Jhumpa Lahiri and George Saunders and James McBride.

One funny moment was when I was standing in line at the beginning of the night: I suddenly realized I was right behind the lovely and fabulous Carrie Brownstein. She saw I was wearing a finalist medal (which all finalists were required to do) and asked me what I thought my chances were of winning. I said zero.

When did you first hear the book was a contender for the award?

I first heard that my book was on the National Book Award long list from a couple of congratulatory e-mails when I checked my e-mail that September morning. My first reaction was confusion. It took me a little while to figure on what my friends were congratulating me for. “Congrats on making the NBA list!” I remember one saying. I googled my name and NBA, not even realizing at first what “NBA” stood for.

You spoke in your acceptance speech about the power of “speaking differently” in poetry. How did you attempt to do that in Incarnadine?

I attempt to “speak differently” in multiple ways in this collection, and to do that I turn to different forms, voices, perspectives, and tones. Speaking differently is not just about finding alternate words for the same idea but about considering things in new ways; seeing differently and speaking differently are intimately connected. For example, one poem in this collection is called “Annunciation as Fender’s Blue Butterfly with Kincaid’s Lupine.” By calling an encounter between an endangered butterfly and flower a kind of annunciation, I am speaking of it, I think, in an unfamiliar way, and asking that it be considered in a new way. We expect an annunciation to be the scene of a beginning, not an ending.

You grew up attending Annunciation Church in Pennsylvania, staring up at stained–glass depictions of the Annunciation scene. How would you describe the role of spiritual faith in your life and your work?

When I was young, spiritual faith had an enormous presence in my life. When I was a young adult, its absence, at times, felt enormous. Now my relationship to it is more complicated, and I try to let those complications into my poems. W. H. Auden once said that “poetry might be described as the clear expression of mixed feelings,” and my mixed feelings about faith and spirituality often drive my work.

Incarnadine grapples with ambiguity and uncertainty throughout. Did the process of writing these poems provide any spiritual clarity?

I don’t think I was ever after spiritual clarity, at least not the kind that might be held as an enduring truth. An insight that helps me through the struggles of one day will not necessarily answer to the spiritual unrest of another. That is, I think, why artists keep creating and writers keep writing. We change; our world changes; what suffices one day will not necessarily suffice the next day. We need new visions. I like Robert Frost’s idea that a poem is a “momentary stay against confusion.” Clarity may be “momentary”—but that does not make it less valuable or needed.

Incarnadine examines disjunction so lyrically—whether it’s between the sacred and carnal, corporal and the inhuman, faith and unbelief. I love how the poetic forms reflect that. How did you decide what structures would best complement each poem?

I discover this largely through trial and error. I try to take risks with form; most of them fail, but every once in a while, something catches. That is why, I think, poetry requires patience. I had to give myself permission to fail a lot in order to find what, as Wallace Stevens might say, would “suffice.” It took me ten years to write this book.

Would you describe Incarnadine as a feminist response to the biblical annunciation?

It strikes me that I have never described Incarnadine—to anyone, including myself— as a feminist response, and now I wonder why. Feminism means, in its most basic sense, a belief that men and women should have equal rights and opportunities. I do, of course, believe that. Feminism might also be described as activity in support of women’s interests, and I think Incarnadine does answer to that description.

I grew up identifying with the icon of Mary, mother of God, since I was named after her. I also felt myself to be in her shadow. I think Mary is a problematic ideal to hold up to women for many reasons; she is celebrated for being both mother and virgin—an impossible ideal. It is particularly the virginity ideal that is held up to women (and not men) that I find problematic, and virginity is a concept and expectation that still has real and often dire consequences for women throughout the world. I wanted to complicate the figure of Mary and the way she relates to this “ideal.” So my answer is yes: I would say this is a feminist response.

The word incarnadine describes a vibrant, visceral red, and yet cerulean tones are the dominant colors throughout your book. What meaning is behind the tension between these two colors?

These are the two colors that are most associated with the figure of the Virgin Mary, the two colors in which painters have traditionally dressed her. In thinking about the relationship of these two colors, I thought of Carl Sagan’s explanation of why the earth appears blue from space. “. . .[T]he blue,” he says, “comes partly from the sea, partly from the sky. While water in a glass is transparent, it absorbs slightly more red light than blue. . . the red light is absorbed out and what gets reflected back to space is mainly blue.” I wanted blue to dominate the poems as the color that is “reflected back” and therefore visible—but that doesn’t mean red, with all the passions associated with that color, is not there.

What books are on your bookshelf right now?

“Song & Error” by Averill Curdy, “September” by Rachel Jamison Webster, “Two-Headed Nightingale” by Shara Lessley, “An Ethic” by Christina Davis, “Headwaters” by Ellen Bryant Voigt, “Selected Translations” by W. S. Merwin, “Absence & Presence” by Lisa Steinman, and “Gospel” by Samiya Bashir. I am astonished by what so many poets are thinking and imagining and writing right now.

What’s next for you?

I am writing a new collection that is loosely in dialogue with Teresa of Avila’s famous sixteenth-century work Interior Castle. Rather than providing many variations on a moment of encounter, as Incarnadine does, this book will take up the challenge of a spiritual journey. Teresa of Avila imagines the soul as a mansion, and she describes the troubled journey of traveling to the innermost interior of the soul to reach god. I am attracted to inward journeys, but I am also wary and a bit suspicious of them. That two-mindedness is the starting point of my new collection.