How the Oregon Dunes Inspired Sci-Fi Classic 'Dune'

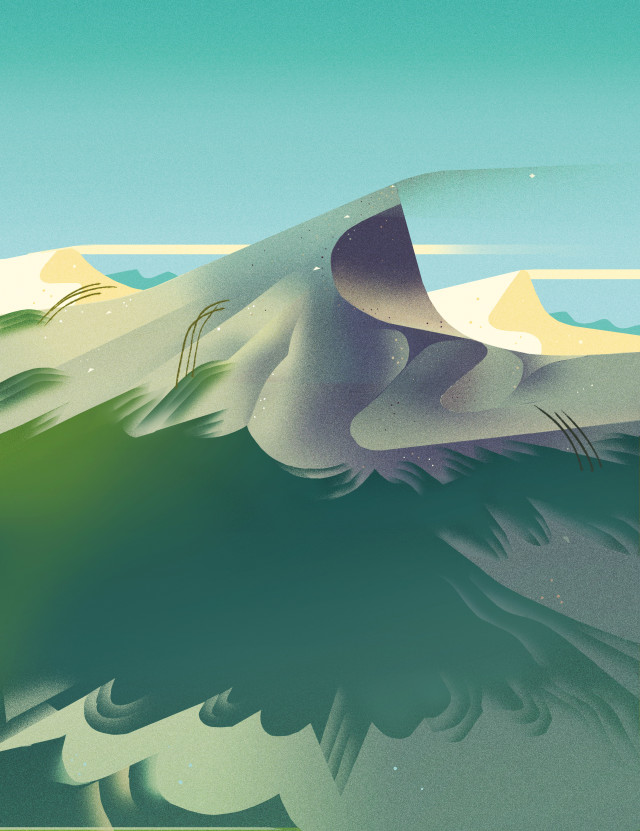

Image: Elle Michalka

I stand at the edge of the Oregon Dunes. Spanning 40 square miles along the coastline between Florence and Coos Bay, a rippling blanket of sand rolls away in every direction, pockmarked with life: islands of shore pine trees and, everywhere, tufts of pale beach grass. Half a century ago, this place bore a more menacing aspect, as sand encroached within feet of railroads and highway, destroyed forests and vegetation, and threatened water supplies. In 1957, a Seattle journalist named Frank Herbert learned of a new attempt to tame the dunes: the feds would plant 300 acres of European beach grass near the Siuslaw River. He chartered a plane to Florence.

The seemingly unstoppable force of the encroaching sands would inspire Herbert to imagine a faraway planet, consumed entirely by sand, which he called Arrakis: The effect of Arrakis on the mind of the newcomer usually is that of overpowering barren land. The stranger might think nothing could live or grow in the open here, that this was the true wasteland that had never been fertile and never would be. Herbert’s novel Dune, published 50 years ago, blended ecology, philosophy, and adventure. The book spawned five sequels written by Herbert, who died in 1986, and 13 (and counting) cowritten by his son Brian Herbert, as well as a cult-classic film.

Today, the landscape that inspired the sci-fi survival classic is itself in danger. The extensive shallow root system of that European beach grass, a nonnative species common in coastlines of Europe and Africa, did more than stabilize the sand.

“The grasses transformed the landscape and created natural barriers,” says Sally Hacker, a professor of ecology at Oregon State. “But this process has caused the decline of a number of native beach and dune species.”

Native species like the flowering plant silvery phacelia, Siuslaw hairy-necked beetle, and the shorebird snowy plover stand at serious risk of extinction due to habitat loss. Specialists advocate for various approaches to the problem; Hacker, for her part, recommends small-scale reductions of European beach grass, which also helps protect against flooding.

“Dunes occur at the nexus between humans and climate change and thus will be highly influenced by how these processes change with time,” she says.

In an odd way, present-day scientists like Hacker are just the audience Frank Herbert had in mind 50 years ago. Dune’s dedication is a frank call for continued science: “To the people whose labors go beyond ideas into the realm of ‘real materials’—to the dry-land ecologists, wherever they may be, in whatever time they work, this effort at prediction is dedicated in humility and admiration.”

“My father emphasized a world view of living in harmony with nature,” says Brian Herbert. “The dunes got him thinking more about man’s involvement in relation to it.”