What's it Like to Travel the Oregon Trail in a Covered Wagon in the 21st Century?

Rinker Buck on the Oregon Trail. (Photo courtesy Rinker Buck)

When Rinker Buck took a road trip in 2010, he didn’t just slip behind the wheel and put his foot on the gas like your average American road tripper. Instead, he set off in a 19th century wagon with a team of occasionally cantankerous mules, a Jack Russell called Olive Oyl, and his younger brother Nick. Their route? The full length of the Oregon Trail, making them the first to travel it in over a century.

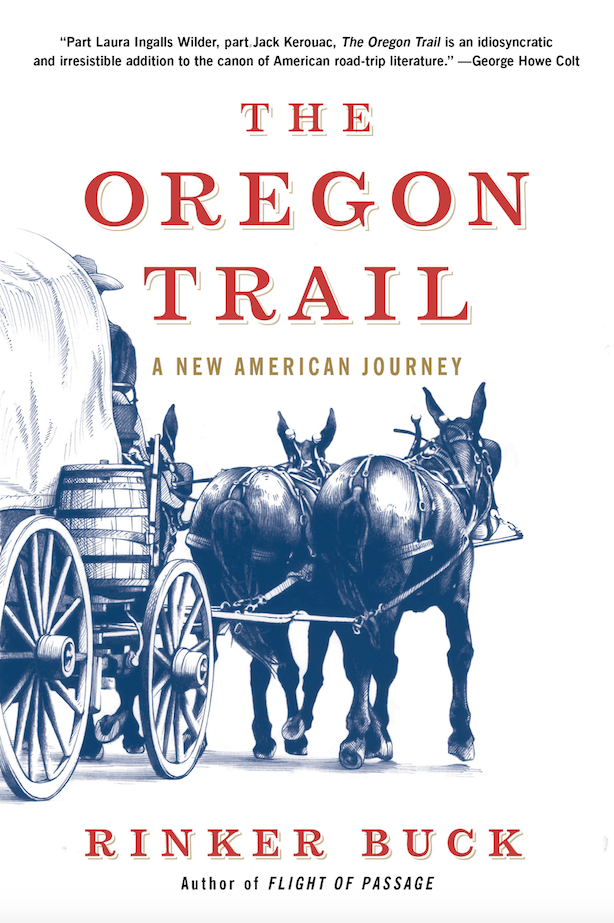

Buck documents the experience in his acclaimed book The Oregon Trail—hailed by the New York Times as an “absorbing” adventure story, and by the Boston Globe as “charming, big-hearted, impassioned and a lot of fun to read”. Ahead of his reading at Powell’s on Thursday, we caught up with the peripatetic writer to find out why one apparently sane, middle-aged man would travel over 2,000 miles by wagon—and what he learned when he did.

What galvanized you to set off in a covered wagon along a centuries-old trail?

It sounds like an adventure tale but it’s really more driven by history. I was in Kansas, working on a journalism story and I came across a trail mark for the Oregon Trail. As a history nut it bothered me a lot that I didn’t know more about the trail. Then I started researching it. The thing that’s fascinating about the trail is all the things that they don’t tell you in history class. I wanted to tell the real history of the trail. Then in one of the history books I came across this statement that the last documented crossing of the trail was 1909. And I thought, why don’t I just ride the trail?

Was it hard to make it happen?

My brother and I bought some mules, and over the phone I bought a restored 19th century wagon, and it was that simple. It stopped being that simple the day we left.

So things got challenging pretty quickly...

If I’d known all the problems we were going to have and all the things I’d miss and all the problems I was going to have to solve, we never would have left. The book is sort of an ode to having a dream and then realizing your dream doesn’t make a lot of sense, but to actualize it and follow through on it you’re just going to have to improvise. And more important than the land we crossed was learning to live with uncertainty. So yeah, I still think it was pretty crazy, but there’s a lot to be said for impetuosity.

Were there any moments along the way where you genuinely feared for your life?

Rinker Buck at an Oregon Trail marking. (Photo courtesy Rinker Buck)

There were a few. A few times we had to take bridges across high water. The rivers were so full and the mules would panic when we got up on top of the bridges, because there’s nothing in their DNA that prepares them for being 150 feet above the water.

But the single hardest day and most precarious time was when we took the end of the Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff which is a section of the trail in Western Wyoming. We took it up to 8,300 feet and then in less than two miles we had to descend down a mountainside to 6,000 feet. So we made a 2,000 foot descent in about a mile and a half. It was so steep that the mules were so far below us, and we had to chain our wheels so that the wagons would skid along. The wagon was a little over five feet across and this was all on a trail that was seven feet wide. To the left of us was a 300-foot cliff. So if anything had happened, if the mules had got skittish, we would have gone over the side. That descent took us about two or three hours, and the whole way down we were literally one step away from death.

How did the following in the literal footsteps of the pioneers change your understanding of the trail’s historical context?

All of us, especially big history readers like me, are creatures of our reading, and I’d always pretty much accepted the idea that Americans were bound to do this, that we were too ambitious and too active—this notion of ‘manifest destiny’. But in fact that’s not accurate. Many people were homeless because there were successive bank failures, and that drove a lot of people to the trails. Religious rivalries also became so unbearable that people simply left on the trail because they wanted religious freedom. So those are very different motives than ‘manifest destiny’. Most of these people were on the trail because they had to be, they were financially desperate or very uncomfortable in their lives.

One day, my brother Nick and I were going along, and it had been a long day, one of those days when the wind was always in your face, or the mules were a little cranky, and we both looked at each other in the wagon seat and said, ‘You know, nobody would do this unless they had to. This is too hard.’ That was a big insight, because once you know that from riding the trail, your understanding of American history becomes different.

You highlight the stories of a number of characters from history—pioneers who traveled the trail before you and helped shape the story of America. Who were the standouts for you?

The Oregon Trail

Narcissa Whitman was an evangelist from upstate New York, who decided to go out and ‘educate the Indians’ as far west as she could get. So she and her husband set off, and she became the first white woman to cross the Rockies. But she sent home a series of letters that were published in newspapers, and those letters led to an explosion of traffic on the Oregon trail in much the same way as Cheryl Strayed’s book Wild has done to the PCT. Whitman had this huge impact but she’s completely forgotten today.

I was also impressed by Abigail Scott and Margaret Frink. They defied the stereotype of women crossing the trail, which was that their husbands had forced them into it and their role was to ride the wagon all day and hurry the children along. But these pioneer journalists rode across the trail side saddle.

Another character I really loved was named Ezra Meeker—he was the first trail preservationist. He first crossed as a pioneer, made a fortune raising hops, then lost everything and devoted the rest of his life to promoting the preservation of the Oregon Trail. He went out and put stone markers on it, and the fact that the trail ended up being preserved and marked—that would never have happened without him.

Early on you divested yourself of many items—vegetable steamers, your ironing spray, even your GPS. What was it like to return to all of these afterwards? Did any remain permanently decommissioned?

I think the trip actually had a cleansing effect on me. I’m not as into possessions and living in one place and so forth as I used to be. I’m a lot more itinerant now, sort of a vagabond almost, and I find that I like it. I think the trail gave me coping skills that I was going to need pretty quickly in my life, and it taught me not to be so settled, not so worried about what my house looks like . . . just to live.

Rinker Buck reads from The Oregon Trail at Powell's

on Burnside on Thursday, July 31 at 7.30 pm.