Behind the Curtain: Meet the People Who Make the Portland Art World Possible

GRIMM REAPER

How to stage a zombie apocalypse

Katie Rasmussen: location manager / Grimm

Image: Molly Mendoza

STEP 1: Read the script “You use your imagination as a location scout. At the end of season 2 we had a zombie scene. I read the script and thought, ‘Oh my God, it’s at one of those quintessential shipping container yards.’ We can either go to an active container yard and convince them to have a massive film crew of about 200 people there or we go to a plot of land that feels industrial and then bring in the containers.” STEP 2: Use Google “I found out what container yards there are in Portland and jumped on Google maps to rule out things that obviously weren’t going to work. I looked at Northwest Container Services, and saw that they had the biggest, baddest container yard of them all. So of course that’s the one I wanted.” STEP 3: Make contact “We had a conversation about logistics, and then I had to physically go to the site, walk around with them, take photos of the entire thing, and discuss what the limitations of filming there were.” STEP 4: Get the director on board “We jumped in a van with the director and looked at two container yards. But when he saw Northwest Container Services, he said, ‘Yes! This is what I wanted!’” STEP 5: The technical scout “All 30 department heads—art, set decoration, lighting, camera, construction, paint—went to the location and hammered out details, like ‘We’re going to have a bunch of rigging and ropes so that we can do a stunt rehearsal for the filming.’” STEP 6: Filming day “When you see all the big film trucks, and the catering tents, and the RVs in the parking lot, that’s all the job of the location team, too. Everything the camera doesn’t see, we’re responsible for. STEP 7: The payoff “One out of every five times I’ll read a script with a location in mind, they’ll choose that location, I’ll see it on screen, and it looks exactly what I imagined when I read the script. That’s really rewarding.”

SHINE ON

Lighting up the Schnitz

Justin Dunlap: Master electrician / Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall

Image: Molly Mendoza

The lights go down at the Schnitz, and a current of anticipation runs through the audience. That moment of darkness belongs to Justin Dunlap, the man who will light the stage for the evening’s performance.

If you’ve got a seat, swivel around 180 degrees. At the top of the theater you’ll see a row of windows. That’s the lighting booth, Dunlap’s office for more than a decade, where a lighting console and—if he’s lucky—a set list for whoever’s performing form his toolbox for an evening’s work. Dunlap lights the Schnitz for any act that doesn’t bring its own lighting team, including every Oregon Symphony show. Each time, he designs it all from scratch. “I control every light,” he says, “and tell it what color to be in, what pattern to be in, what intensity, and where it’s positioned. I record that set of instructions as a cue, record multiple cues, and then link them together.”

When the show boasts only one performer, the lighting is kept “static” so as not to distract from the individual. With a full band or a symphony performance, lighting helps train the eye on the changes in focus. “If the strings are doing a flourish, take them into a contrasting color for that second,” Dunlap says. “Then bring it back to a full stage ‘wash’—where the whole area is covered in the same color. Or if the soloist is downstage, bring that person out while leaving the rest of the stage in one static color.”

You won’t see Dunlap when the curtain rises, but he still makes his mark on your experience. “Once you come into the space, everything you see, hear, and smell has to do with how you’re going to interpret the piece of art put in front of you that night,” he says. “All of it has an impact on the show.”

FRAMED!

Hanging Monets at the Portland Art Museum

Matthew Juniper: chief preparator / Portland Art Museum

Image: Molly Mendoza

Examining a Francis Bacon triptych at the Portland Art Museum can feel like the closest possible encounter with genius. There it is, just a few feet away, close enough to parse individual brush strokes. But one man gets closer still: Matthew Juniper, the museum’s chief preparator, handles and hangs most of the works that grace its gallery walls. His job provides him with a very different interaction with visual art. “You can study it much more closely,” he says. “You can tell how heavy it is, what it smells like.”

In his 20 or so years at the museum, Juniper has handled everything from Monet paintings to Chris Burden installations. He works with curators to locate pieces in the museum’s vast vaults and organizes their presentation in exhibits. “Do they want it on the wall? On a pedestal? Do they need a mount to support it in a particular position? Do they want it lit in a particular way? Will we need any special equipment to install it?”

For special exhibitions, trucks and crates arrive bearing treasures: The Ox Cart from Vincent van Gogh, or a golden dragon head from Ai Weiwei. “In 2012, there was a piece called Blitzschlag mit Lichtschein auf Hirsch (Lightning with Stag in its Glare) by Joseph Beuys, which hangs from a large steel beam,” Juniper recalls. “I had to devise a way to suspend the piece, and we didn’t want to alter our building in any way. I worked with a contractor who helped fabricate the beam and ‘towers’ that hold the hanging portion of the sculpture. The piece barely fit into our building laying down. Once inside, it had to be righted and then rigged to lift it onto the beam.” The arrangement of the piece—a bronze slab hanging from the beam just a few millimeters from the floor—was essential to its artistic content. Gallery patrons were left to ponder the energy of the primordial; for Juniper, it was all in a day’s work.

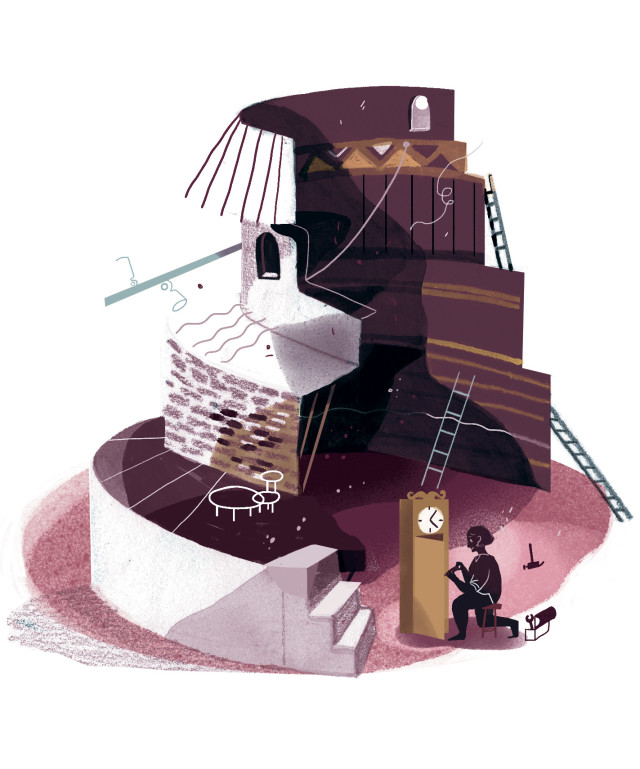

PROP SHOP

How to make an opera tick

Cindy Felice: Properties Supervisor / Portland Opera

Image: Molly Mendoza

STEP 1: The prop requirement ”The director and set designer came up with a set for Spanish Hour. I was given a model of the set, and pictures of two antique clocks with a description of what they needed to do: they were central to the plot, and had to be lightweight enough to be picked up and handled, big enough to fit a person inside, with some kind of back door that the singers could exit from.” STEP 2: The prototype “I drew measurements out on paper so we could see if somebody would be able to bend down inside the clock. And from there we built a prototype, a box of thin plywood.” STEP 3: The first trial ”We brought the prototype to a meeting with the director, the singers, the production manager, and the set designer. We had singers get inside and check if there was enough room for them to move around. It turned out the clocks needed to be bigger.” STEP 4: Building the clocks ”I started thinking about material, and came up with a lightweight foamboard called gatorboard. Then we found a way to take wooden molding and bond it to the gatorboard using Gorilla Glue. We started building the real thing. According to the plot, a singer needed to be able to pick up the clocks and carry them. We saw where the clocks needed to have handles, and modified the shape of one of the clocks so it could be more easily carried. Then we put all the molding and trim on them so they looked of the period, and painted them.” STEP 5: Refining and modifying ”Once they were in rehearsals, there were constant modifications! We would drive them back and forth between the studio and the prop shop on a daily basis. It was really tortuous—we were really tired of them by the end.” STEP 6: The afterlife ”We keep props like that in case we want to do the show again, or in case some other company will call to rent them. But right now, the two clocks are sitting behind our break table in the prop shop. We have them on display.”

PAGE MAKER

The designer behind every Hawthorne book

Adam McIsaac: CREATIVE DIRECTOR / Hawthorne Books

Image: Molly Mendoza

Forty-one books, on subjects ranging from Portland food to lobotomies: that’s the entire oeuvre of Hawthorne Books since the small independent publisher started in 2001. Adam McIsaac has designed—from cover to cover and each page in between—every single one. “Every letter in those things, I’ve touched, for good or ill,” he says. “I’ve always been fascinated by the shape of language.”

The 47-year-old advertising creative has worked with Cadillac and Comedy Central. But as an avid reader, he finds his work with Hawthorne, which came about through a long acquaintance with publisher Rhonda Hughes, has a particular appeal.

Early on, he made two decisions: he’d read every book at least three times, and he would devise a unifying house style for the imprint, which publishes four to six books a year with an emphasis on literary fiction and nonfiction essays and memoir, including authors such as Tom Spanbauer and Lidia Yuknavitch. He came up with an aesthetic, both graphic and textual, at once arresting and enigmatic. “The books don’t all look the same, but there’s a unifying principle behind them,” he says, citing the iconic Penguin paperbacks of the 1960s as one inspiration. “They were wonderful books, really well executed and inexpensive. Those were the same values that we wanted to put across.”

And for McIsaac, it’s not just about selling books. “I don’t write because I don’t have anything to say,” he says. “Making these books is a way for me to be part of literature.”

BACH HAND

The player keeping the ballet en pointe

Irina Goldberg: principal Accompanist / OBT

Image: Molly Mendoza

When Irina Goldberg moved to Portland from Uzbekistan 20 years ago, nothing was easy. A conservatory-trained piano teacher, the native Russian speaker found herself in a foreign country with two small children, while in the throes of a divorce. When a fellow immigrant suggested she fill in playing piano for a ballet class at Oregon Ballet Theatre, she worried about her lack of fluency in English. But the friend, also a pianist, insisted, teaching her the kind of cadence needed to accompany ballet.

“It started like that: one class, then a second class,” she says now. “And after a couple of months, they offered me a full-time job.” Goldberg, now 54, is still the company’s principal accompanist. “It’s a pleasure to play for them,” she says.

Every morning during rehearsal periods, OBT convenes what’s known as the “company class,” designed to perfect dancers’ technique and physical and artistic qualities, in one of the dance studios at its current headquarters in Southeast Portland. And every morning, Goldberg is at the piano. She watches OBT artistic director Kevin Irving lead the class, and plays whatever she deems appropriate to accompany it.

“When he demonstrates the steps, you can tell the time signature,” she says. “You know: ‘This is waltz music, this is more polka.’”

Her favorite music? “Classical, of course,” she says. “Opera and Bach. Bach is timeless.”

But Goldberg, who has seen every OBT show since she joined the company, sometimes likes to bring something of her former life into her American milieu. “Sometimes I play Russian music from my memories, which they always like. It’s dramatic, powerful music.” Those are the pieces, she says, that she can play by heart.