KINK FM's Big Voice Sheila Hamilton Opens Up About Suicide and Mental Illness

Image courtesy Sheila Hamilton

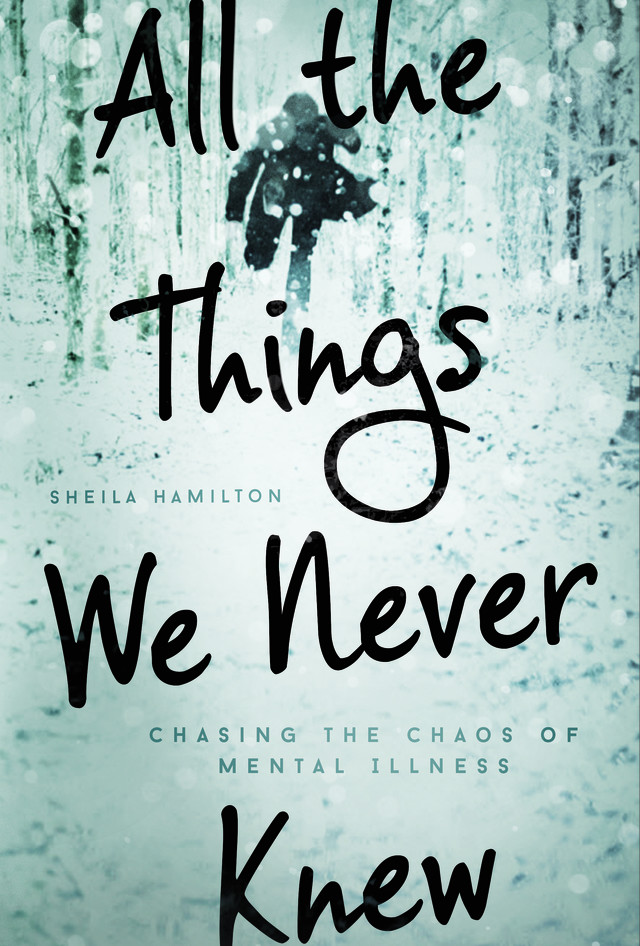

Eight years ago, when their daughter was nine years old, Sheila Hamilton’s husband David drove up to the Columbia Gorge and killed himself. Hamilton was left with burning questions about what had gone wrong, guilt about any part she herself had unwittingly played, and the hundreds of thousands of dollars of debt he had accumulated. Now the Emmy Award-winning journalist has published a memoir—All the Things We Never Knew—of her romance with David, his descent into mental illness, and her attempt to pick up the pieces after he died, interspersed with information Hamilton culled from two years of investigative work into the treatment of mental illness, in particular bipolar disorder.

We spoke to Hamilton about writing as therapy, guilt after suicide, and why she thinks our approach to treating mental illness needs to change.

Why did you write All the Things We Never Knew?

When I was going through this crisis with David I of course went to Powell’s to try and find any kind of resource, because I really learn from memoirs and reading other people’s accounts of how they manage. But there really was not a lot for caregivers. And it seemed to me if this problem was so widespread, we’d have more people giving us road signs for ‘Here’s how you access help’ and ‘This worked for me.’

Tell us about the process of writing the book.

I wrote part of it as a memoir, saying ‘This was the experience I had’, and then I shelved it while I did a really in-depth reporting piece. Then I put those informational pieces in between the chapters, so that people would have the resources: Here’s how you find your local NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness), here’s how the National Institute for Mental Health does science, here’s what’s happening with the recovery effort in America, here’s how other countries are handling mental illness. I’m hoping people will use it not just as a great story, but as a resource.

Why did you first start committing your experience to paper?

I was in so much trauma after David completed suicide that I really felt like I had to understand what I missed. I had to understand what I did wrong. I needed to hold myself accountable for everything that had happened. I did it because I had to. It was a very strange experience—the story seriously just moved through me because I felt that I needed to get it all down on paper.

Going back to your life with David, was he open with you about his illness from early on?

Listen, if he had come to me the very fist time he felt depressed—he had bipolar 2, so he was in that agitated, irritable depression for most of it, I didn’t actually see mania until the very end—but if he had come to me and said “I’m actually really depressed and I need your help,” I honestly think I would still be married to him. I think he’d be alive. I think we would have grown deeper and become more intimate. Instead, his way of coping with his really terrible feelings about himself was to become this human being who wasn’t very likable. He cheated, he lied, he denied anything was wrong, he placed blame on me when I tried to say “Are you OK?" It was a very confusing time, being in a relationship with a person who was denying mental illness. It was a serious illness and he was a great compensator. One of his doctors said: “He carried off one of the biggest psychological frauds I’ve ever witnessed.”

When did you first start to piece things together and realize he was mentally ill?

There are so many times now that I think “Oh God, how did I miss that?”…I was working and came home early, and he was standing by the door. We’d just moved again because he said he had a problem with noise and light and the house we were in was too busy. We’d just moved to a house that was a block from a very busy intersection—it was as far as I knew delightfully quiet—and he was standing there with a yellow pad and noting every car that came past. He was agitated and sweating and his rage over traffic was so out of proportion with most people’s emotions. I thought “Whoa, something is wrong, something is so wrong.” And instead of saying “No, you need help and that’s it,” I said “No, you need help.” And then we moved again.

He was very good at coming back into the present, and opening this window of clarity and loving me again, and welcoming my daughter into his activities. I kept holding on for those moments of a family together. I was painfully optimistic.

I also think people get really the wrong impression of mental illness, that a person who’s suffering is always acting out—they’re not! He was keeping a multi-million dollar business together, at least to the end until it felt apart, he was helping raise our daughter, he was phenomenal as a father, he had all these things in his life that he was doing well and then he’d have these behaviors that would bubble up…But it waxed and it waned. It was very difficult for me to figure out, and that’s the nature of bipolar. It’s such a strange illness.

You describe a very steep decline after he was finally diagnosed. What happened?

I have a really strong belief that he might have been able to continue to compensate but he had three major traumas. His business was finally going under because he’d been so depressed he wasn’t actually billing his clients. His father died, who he had a very difficult relationship with, and I had finally decided to separate from him, after learning he was cheating again. It was three things all at once.

Then a very well-meaning friend who was a physician ended up putting him on antidepressants, and within 48 hours of him being put on those antidepressants he had his first manic episode and went into akathisia—he said it felt as if his skin was crawling. I don’t think he slept again over the course of the next month until he was hospitalized, he lost 15 pounds like that, he was pacing at all hours of the night—he was in so much trouble.

You recount that he attempted suicide more than once—did that trigger some kind of treatment plan?

We attempted to try and get him hospitalized the first time he attempted (suicide) and he flipped and said “I’m fine, I’m not at risk to anyone.” And they believed him. The second time, he attempted suicide it was very serious. They got him hospitalized, and his experience in psychiatric care was probably the thing that tipped him over. Essentially they said to him, “You will never recover from this, you are always going to be this way.” I think he really lost hope. So the day after he was released, he drove to the Gorge and found the gun that he had hidden from the first attempt, and killed himself.

It feels like it’s yesterday. I have never recovered from the trauma of his death. Because he was one of the most gentle, brilliant human beings I’ve ever met, and the idea that part of it was my inability to see clearly and also my unwillingness to accept, “This guy is really sick, he needs help, I need to drop everything else I’m doing and get him help.” I think like a lot of people who are suicide survivors, there’s always the notion of what more could I have done. It never goes away.

Is it hard for you to speak about it now, eight years since?

I guess I kind of knew going into it that if there was any degree of interest in this book at all, I was going to need to speak about it. I feel David’s silence and the shame around mental illness was part of the reason it got so bad. I want to be able to bust that paradigm open.

Do you think a different treatment could have helped?

He couldn’t believe that he’d ever have a life worth living again, and I think that’s such a lie. He didn’t get the kind of care that allowed him to see past it. It was very much based on medication, medication, more medication, and medication, and not a lot of the therapies that are being proven to be very effective.

In new compassionate models of care, which a lot of hospitals are moving to, it’s going to be based on behavioral outcomes that they know are working. They’re going to be asking people to engage in music therapy, in yoga, in mindfulness-based therapy—these tools must be combined with medications because it gives people the ability to cope with their thoughts. We know that half of the people who complete suicide have actually been under a doctor’s care. There’s something really wrong with that statistic. If it were just a matter of “Oh we can’t get access but we’re delivering this phenomenal care,” that would be one thing. But the truth is half of these people are getting the care, they’re under the medication, and they’re still completing suicide. Something’s wrong. Medication alone doesn’t solve a problem that’s spiritual, it’s economic, it’s sometimes physical: mental illness encompasses the whole body, the whole person, the whole being, and we’ve just been treating one thing—the brain chemistry.

Did it help you to write the book?

I felt like it was the best therapy I could have. I was in a really tough financial position because his debts and what he’d done with his business was now my problem as a married person. And I didn’t know if I was going to be able to keep my house, and I wasn’t going to be able to afford a lot of therapy. When I started writing I had this same experience that you have in therapy which is “Talk to me, tell me what happened, recount your emotions, what you were going through,” which was incredibly helpful. What was so hopeful for me was that I recognized my own patterns of compartmentalizing my emotions and being able to keep myself apart form the trauma and I just allowed myself to learn how to cope. I learned almost every skill in the tool box of being able to cope that I would tell somebody who has bipolar they need to learn, and it’s the most transformative thing I’ve ever gone through.

Has your daughter read the book?

Yes, and the highest praise I’ve ever received, she said: "You got it right."

What would you suggest to caregivers, people close to someone suffering from mental illness?

Certainly NAMI is the best, it’s so helpful in terms of peer support and in terms of educational groups and ways in which you can deal with your loved ones. I love this conversation that we’re having now around a book, because the more stories that we can share about what worked, the more people can share about how they recovered and how they’re living well with mental illness, that’s what’s going to change, that’s going to change the paradigm.

There’s going to be some woman ten years from now who goes to the same aisle that I was looking in, and is going to find five books about caregiving and support and what your options are. What a dream that would be!

Sheila Hamilton will be at Powell's City of Books on Tuesday, October 20.