Can Portland Artists Survive the City’s New Gilded Age?

Two vastly different buildings flank the east end of the Burnside Bridge, like a physical parenthesis summarizing how Portland is changing. On the north side, a 21-story tower that suggests a glass-fronted open book began climbing less than a year ago. On the south stands a five-story, redbrick edifice capped by a rusty water tower, built in 1916 and bearing its name, Towne Storage, big and bold like an old-time newspaper’s masthead.

Up until last fall, dozens of artists, craftspeople, and creative entrepreneurs operated in the Towne Storage Building, riding an antiquated elevator to cheap studios—a bargain roost for Portland’s “creative class,” within sight of downtown’s skyscrapers. Then the Towne sold for $3.9 million; the new owners evicted the building’s tenants to make way for its redevelopment into commercial space.

To many, the moment represented how Portland’s rising cost of living and booming real estate market are scattering its artists—and, in a larger sense, how a shiny, more expensive New Portland is sweeping aside the scruffier, less polished predecessor. (The sleek new Yard building across the street, by the way, will soon be home to apartments, commercial spaces, and a hot-spring-inspired spa.)

“They gave us 60 days’ eviction notice,” says Kailee McMurran, a graphic artist whose company Design by Goats, cofounded with partner Duke Stebbins, operated out of Towne Storage. “Before we found a new space,” she says, “we went to four or five different places, which were more expensive than our Towne studio and smaller. We were getting to the point of asking, ‘Should we stay in Portland? It’s not looking like this is going to be the greatest place to have a studio.’”

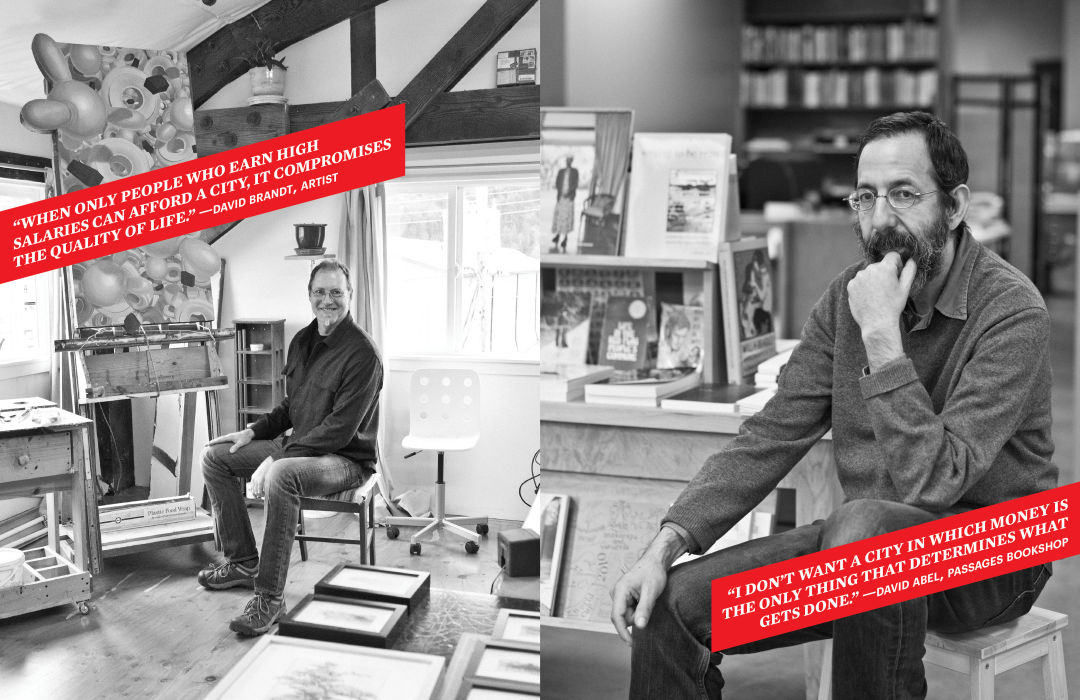

“It was a shock,” says David Abel, a writer who owns Passages Bookshop, which specializes in fine and rare books and early editions. Abel had just settled Passages on Towne Storage’s fifth floor less than a year before, sharing a space with Division Leap, another niche bookstore. The eviction notice plunged him back into the hunt for a home.

“There was that burden of having to do all of the things over again,” he says. “But what was most difficult was how much the real estate landscape had changed in just a year or two.” At Towne Storage, Abel paid a monthly rent of $1 per square foot. Upon receiving his eviction notice, he discovered prevailing rents closer to $2 per square foot, sometimes as high as $3. “I really didn’t know if I was going to be able to find a place that would be feasible.”

Image: Erica J. Mitchell

The rent, as they say, is getting too damn high. At least, that’s how it seems to Portland artists and other “creative” professionals, many of whom premise their careers on the availability of unlovely but cheap workspace. Local artist Alain LeTourneau hopes to plumb the relationship between money, property, and art in a documentary he’s working on, titled Real Estate. “When artists can no longer find an affordable, centrally located living and working space,” he says, “in some cases, they simply stop operating. In other cases, they move further out.”

Of course, all of Portland’s rents are rising. The cost of “flex” space, the industry term closest to the free-form workplaces prized by artists, increased 19 percent last year according to a Portland State University study. Residential rents shot up 12 percent, according to one estimate, evictions proliferated, and the city council declared a housing emergency. Nick Fish, the city commissioner currently in charge of arts policy, oversaw Portland’s housing bureau for many years; he concedes that making a case for affordable arts space becomes more challenging when, as he puts it, people are dying on the streets. “It’s harder to argue that we have an interest in preventing some young creative from giving up on Portland and moving to Detroit,” he says.

But many think that argument is valid: that artists help stoke not only a city’s culture, but its economy. According to Adam Forman, senior researcher at New York–based urban planning think tank Center for an Urban Future, planners and politicians across the country now think differently about how cities thrive. “In the past, it was about giving tax breaks to corporations,” he says. “Now it’s about, how do we attract smart people? College graduates? And the way to do that is to have a booming arts scene.”

As Forman sees it, arts spaces and happenings attract people. They come to a neighborhood for a show, eat at a local restaurant, drink at a nearby bar, shop at a store en route. Not only that, but he sees arts scenes as economic incubators, spawning grounds for new companies—he cites BuzzFeed, the new-media juggernaut recently valued at $1.5 billion, which began as a series of experiments at a New York art and technology nonprofit.

We know what happens next, from watching New York’s SoHo, London’s East End, and probably every other artists’ haven ever. “The problem is,” says Fish, “the artists drawn to Portland because of its reputation and its arts and cultural vibe are being displaced because Portland is becoming unaffordable.”

Wandering through the Carton Service Building at the industrial northern edge of the Pearl District in search of the building’s owner, Ken Unkeles, I meet blank faces. Then one tenant rises from his desk: “There is a guy down here—he looks kind of owner-y.” He brings me to Unkeles’s door. The white-haired landlord to some 300 Portland artists actually looks anything but “owner-y,” casually dressed, wry and approachable, his desk swarmed with bundles of papers and a PC. Work by Portland artists covers the office walls—a rendering of North Portland’s industrial landscape by Carola Penn here, an abstract piece made from recycled cardboard by Chandra Bocci there. Unkeles’s five properties are full, his waiting list long. When the Towne closed, several of the artists displaced came to him.

In the old industrial buildings Unkeles favors—hulks like the North Coast Seed Building in North Portland’s railroad zone, or the former Columbia Sportswear headquarters in St. Johns—new or recently vacated spaces can cost about $1 per square foot. But many of his long-term residents are still paying about half that.

Image: Erica J. Mitchell

“Do artists have the right to space?” the 63-year-old asks. “Not necessarily. But what do you want out of your culture?” Unkeles believes that affordable space is essential to young artists’ development and, in turn, to the city’s development as a whole. “I don’t know that just because you say you’re an artist you should get a free ride, or a subsidy,” he says, “but you’ve got to have opportunity. And if there’s not affordable space, there’s no opportunity.”

For Unkeles, art is too important to a city’s identity to get swept away in a moment of buzz and boom. He worries Portland has not yet figured out how to prioritize culture, in part because a lack of attention from a government juggling many demands. “Art is the endeavor that means something,” he says. “The thing that lasts. If you want to cultivate it, that’s good. If you want to destroy it, that’s a separate thing. But if you’re just so unfocused that you can’t figure out what you’re doing, that’s terrible.”

Unkeles is one of a small group of private Portland businesspeople who support local artists through bricks and mortar. Developer Brian Wannamaker runs several buildings under the aegis of the Falcon Art Community, housing the likes of painters Alexander Rokoff and Samir Khurshid and musician Brent Knopf, best known as a former member of Menomena. Real estate developer Al Solheim is still called the Father of the Pearl District because of the role he played in establishing artist spaces and creative businesses in the area during its redevelopment. Brad Malsin, who pioneered the redevelopment of the Central Eastside Industrial District, where Towne Storage sits, built Milepost 5, an “artists’ community” in Northeast Portland that boasts live-work spaces, work studios, galleries, and a performance space for some 140 owners and renters.

For the most part, these developers are doing it on their own steam. And according to Unkeles, they’re looking to the city not for active help, but rather to remove some of the obstacles and attached costs that come with zoning and development. In the case of Milepost 5, the city, under former mayor Sam Adams—who is credited with the concept in the first place—was instrumental in getting the project off the ground, with Adams himself cutting the ribbon in April 2011.

So why did it stop there? Fish says there’s been “a bit of a drift” in local government’s commitment to the arts under current (but outgoing) Mayor Charlie Hales. He points to urban renewal in neighborhoods like Gateway and Lents. “How come in all the discussions about how to revitalize those two areas, the role of artists has never been part of the discussion?” he asks. “I think it goes to the question of what the government’s role is, and where’s the vision. And right now we don’t have a clear vision to support artists who are being priced out.”

Portland’s escalating rents can feel like an unstoppable force of nature, or at least of capitalism. But there are ideas for action.

Forman, the Center for an Urban Future researcher, suggests making use of public space, like schools. “After 4 p.m. on the weekdays and all the weekends, they’re underutilized,” he points out. “Opening up those facilities to artists when they’re not being used by schools would help.” He also suggests the city look at recreation centers in parks. Other cities across the country have found novel approaches to similar problems: he points to Austin, where the city developed an affordable health care approach for musicians, and Minneapolis, home to ArtSpace, a government-formed nonprofit aimed at creating and preserving affordable space for artists and arts organizations.

If we have the will to preserve and build on Portland’s cultural reputation, these examples could serve as inspiration. And it so happens that the spring brings a primary election for mayor—a time for individual voters and arts organizations to make sure candidates are addressing what’s going on in the arts community.

For his part, Fish says the Portland Development Commission, the city’s urban renewal agency, and the Housing Bureau need to collaborate. “It might be incentives,” he says. “It might be subsidies to get the kind of live-work space that’s permanently affordable that allows artists to stay here,” he says, adding that the city has already found ways to address the housing crisis when it comes to its poorest victims. “But we haven’t taken those principles and applied them to struggling artists. The question is, should we? And, then, whether there is someone in the mayor’s office who wants to lead that effort.”

Meanwhile, the Towne Storage exodus has scattered former tenants all over the city. Months of search finally produced a new home for Passages Books, as David Abel moved into a bright, ground-floor space on NE MLK Jr. Boulevard in November. Kailee McMurran and Design by Goats have migrated to new space in the Jazzercise building on East Burnside.

Though the move was tough on the company, it at least provided McMurran, who also dances with the SubRosa Dance Collective, with artistic inspiration. At January’s Fertile Ground festival, she performed in a dance production called “Displaced.” “My piece is specifically about that happening, because I was displaced out of my creative space in Portland,” she says. The city’s rental crunch, it seems, can inspire art even while making it harder for it to happen.

And while an individual’s work can illustrate one experience, it takes a whole, thriving creative movement to reflect a community’s life. “Artists are often the ones that can capture and critique these changes,” says Forman. “I think artists, more than any other population, can articulate problems in society. You want people who will force Portlanders look in the mirror.”