How Do You Make White People Laugh? Negin Farsad Has Some Suggestions

Image: Ryan Lash

Filmmaker. Stand-up comedian. Book writer. Dual master’s degree-holder. Public policy-maker. Iranian-American. Honey mustard lover. Red lipstick wearer. Negin Farsad defies categorization, being one of those rare people who appears able to do just about everything. Now the brains behind, among other things, The Muslims Are Coming! and Nerdcore Rising, two smart, funny films, has added another line to her resume: memoirist.

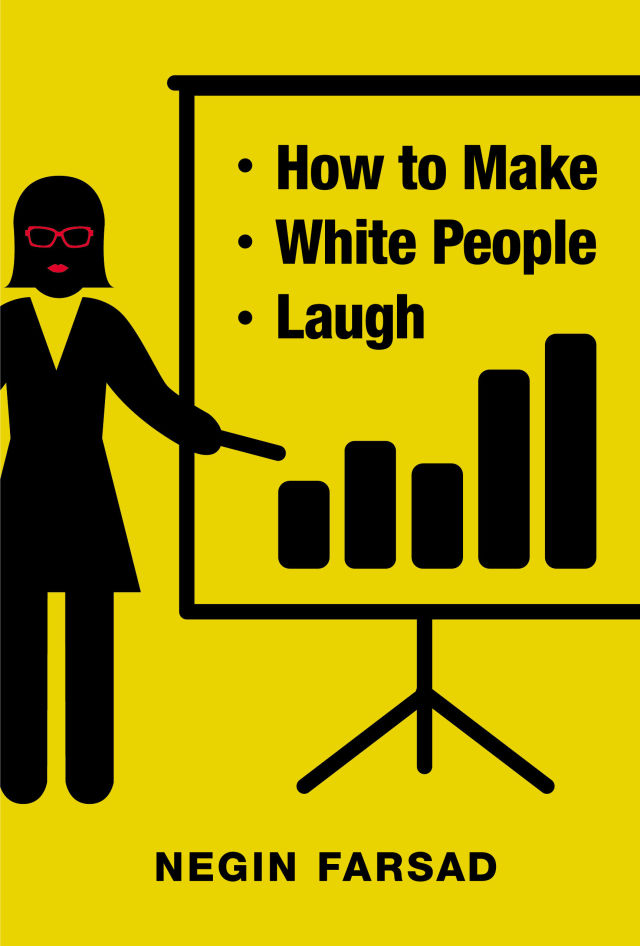

With the recent release of her always-funny part-memoir-part-social-justice-manifesto, How To Make White People Laugh, Farsad has proven, once again, that she has something to say and we should all be listening. And luckily, we can do so without leaving town, as she’s in Portland this weekend for not one but two events.

Ahead of the Portland premiere of her latest film, 3rd Street Blackout, at Living Room Theaters, and her reading at Powell’s for the new book, we talked to Farsad about everything from being a brown woman in a sea of white men to Zac Efron’s abs.

From a senior policy advisor in New York to a stand-up comedian—how did you make that transition?

I got the comedy bug in high school, playing not kitchen wench No. 1 or 2, but kitchen wench No. 3 in our high school musical production of Once Upon A Mattress, so, not to brag, but that’s where things got started. In college, I double-majored in government and theater. I ended up going to grad school for African American Studies, as one does when one is not African American, and also public policy at the Columbia School of International and Public Affairs. I interned for Charlie Rangel. I interned for CSPAN. I ended up working [for the Campaign Finance Board] as a policy analyst. That trajectory was rather normal.

But the weird thing is that on that side, I had constantly been doing comedy. So I would go to a city council meeting, talk about numbers, and then at night, I would go do stand-up and maybe talk about a city council meeting, you know? At some point, it got deeply inappropriate and my friends staged an intervention, and they’re like, “You wanna be a comedian!”

[Comedy] just felt like such a self-serving job. Kind of like anything in the arts feels. It’s about you having to get more name recognition, and it felt gross, because I was really committed to public service, and I wanted to figure out a way where I could be less gross. And so, that’s where I cooked up the notion that I would address social justice issues, which is not to say that I haven’t done my fair share of jobs at MTV and Comedy Central and Nickelodeon and Logo and whatever, writing nonstop jokes about Zac Efron and his abs, and Justin Bieber and his abs. Just a lot of abs. So I’ve definitely done that as well.

In terms of social justice comedy, it seems that that’s more punching up than punching down, and I wonder how the idea of punching up in comedy fits in with writing about Zac Efron and his abs.

I think for me, it was just one of those things where, OK, I’m an ethnic lady, I’m a Muz. Those are things that are not going for me in the professional world of comedy, so in order to legitimize myself I have to be able to do this. I have to prove that I can do this. For every thing I do about bigotry, I have to do a thing that’s white. I made a feature film called Nerdcore Rising about nerds who rap, and I’ve done as much on healthcare reform and bank reform as I have on Islamophobia, so I feel like I try and diversify, A: because I do believe in these issues, and B: when it comes to the less worthy jokes, because I want to be considered a legitimate comedian.

I don’t know if I would feel this particular pressure if I were your average white dude comedian. It’s funny, because before I was ever truly aware of the gender dynamics of the comedy world, before I knew the numbers, before I read the ACLU’s lawsuit on Hollywood [and] gender bias—before any of that, we wrote a sketch called, “White Guys with Brown Hair and Glasses” because there were so many white guys with brown hair and glasses in my sketch-comedy troupe, and we just thought it was hilarious. I remember writing that sketch and then seeing the Daily Show accept an award at the Emmy’s, and they brought out all the writers, and I was like, ‘Wait a second! White guys with brown hair and glasses!’

Do you feel like things are changing, even if slowly, that there’s more space for non-white-dude comics out there?

I think it is getting better. It’s funny because I think what we’re experiencing right now is a little bit of a “two steps forward, one step back” situation.

As an actor who goes on auditions, for a very, very, very long time, the auditions specifically had to say, “It can be any ethnicity” [for me to be considered]. I’d just look at a script and think, “How is it that I can’t audition to be the best friend of the fuckin’ beautiful lead or whatever? It doesn’t make any sense.” But it had to specifically say “any ethnicity.” So it really limited the number of auditions I was sent on. I’ve noticed that in the last eight months or so with this new crop of programming, it’s almost like finally Hollywood is like, "Hey, this ‘any ethnicity’ saying—could we just call them in for any of the parts? Maybe we just make all of the parts any ethnicity." I think that’s becoming a part of it.

I would love to get to the point where we just have characters on a show who just happen to be Muz or whatever and it’s not a big deal. We’re seeing a little bit of that, like with Mr. Robot there’s a Muslim character. Oddly she’s Indian in real life and plays Iranian in the show, which is funny, because she could have just played an Indian.

In my movie, 3rd Street Blackout, which is opening in Portland—one of my things with [this movie] is that I wanted to do a rom-com, and I wanted to play the lead in a rom-com, because we don’t really see Iranian-American ladies as leads in rom-coms. And I wanted it to not be about that, but have the audience see, “Oh hey, she’s ethnic, it’s cool. We’re all aware, and now we can move on from it." That’s where I think we are going, however slowly.

What did the book-writing process look like, especially in comparison to stand-up?

So with stand-up, you have a dumb idea, and you test it that night, and you tell from the audience, 'That part worked, part of it didn’t work." Then you work on it, and you bring it back out. You do that several times. By the end of, like the 20th time, you might have an actual bit.

The book-writing process is like, write this thing. Find it amusing in your head, and then never know for another year and a half if anyone is going to like it. So I was just like, this is traumatizing. What am I even writing? Who is going to read this?

You perform what you call social justice comedy, and in your book, you talk about comedy being the lube, if you will, for starting conversations. Because your comedy is political rather than just humorous, which comes first for you: the laughter or the message?

I think it’s the laughter. I sandwich a lot of my material with so much personal stuff. I can’t convince anyone of my humanity unless they see it on display. One of the fundamentals I think is true is that it’s really hard to hate someone that you know, and by getting to know me as a human being and laughing at me and laughing at my stories, you will get to know me, and it’ll be harder to hate me, and hopefully by extension it’ll be harder to hate people like me. It’s a solid community builder. Whereas politicking or messaging is almost always alienating.

Some comedians have said they consider Portland audiences to be uncomfortable laughing at topics that might be seen as controversial or sensitive. What’s been your experience? Do Portlanders differ from other audiences in their responses to your comedy?

I had a great time [in Portland]. I think that comment that you hear from people sounds very similar to comments from comedians going to liberal arts colleges or very liberal colleges. I think that I sort of lay it out on the line usually, like, "Hey I’m this person. I’m going to say things that might be seen as culturally insensitive, and I don’t mean them that way. It’s just satire." That almost sounds like I have a joke that’s a disclaimer about jokes!

Maybe the only benefit of being an Iranian-American Muslim lady is that I get to say a little bit more about the world without feeling bad about it. It’s not enough of a benefit for me to renew, but it is, I guess, a benefit.

Do you think that has to do with power dynamics? Do you feel that you can step over those boundaries more easily because you’re an Iranian-American Muslim lady?

I think it’s just not threatening to hear a 5-foot-three woman who is brown and dressed like a cartoon—it’s not threatening. It feels like, let her say her little thing, and then the world will go on not caring about her. I don’t know if that means I can push harder or anything. I’m just not a threat.

How do you make white people laugh?

[laughs] The joke is that it’s not different at all. But part of the reason I titled it that way is because, I’ve been trying to figure this out. This is the epitaph of my career: She was trying to figure out how to make white people laugh the whole time. Again, it’s because they control [things like] the breeding of small dogs and printer ink cartridges. If they’re happy and looped up, they’ll start fewer wars.

It’s still an ongoing question: how do you make white people laugh? I know I wrote a book about it, but if someone else knows, let me know, because there’s plenty of room for an addendum.

Negin Farsad reads at Powell's on Saturday, June 11 at 4 p.m.