This Oregon Author Wrote a Book about a Family of Latvian Gravediggers

Image: Annie Beedy

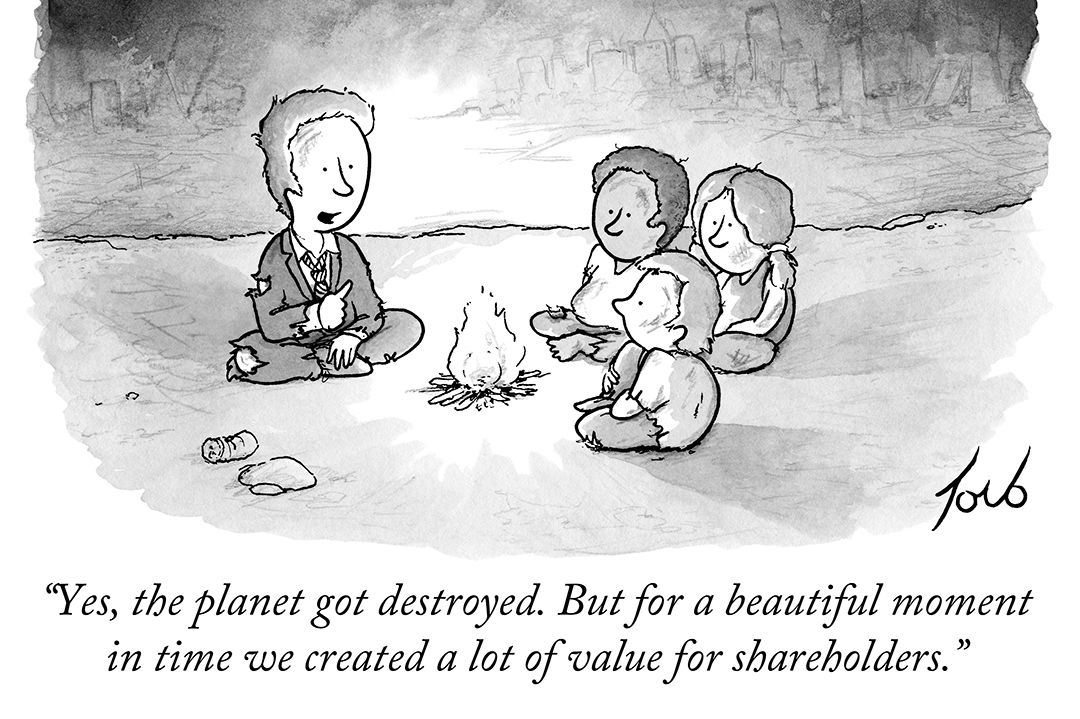

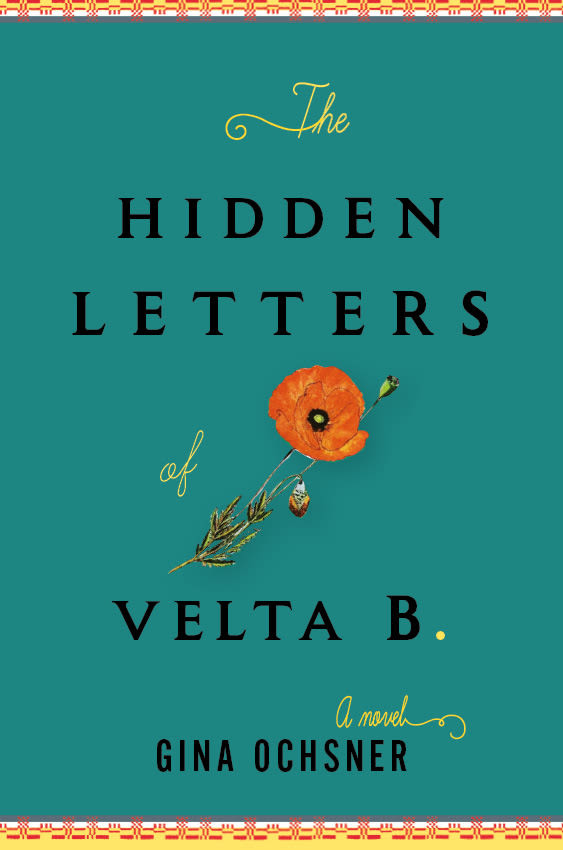

Gina Ochsner is a born storyteller. Even in conversation, she weaves strange and miraculous happenings into her answers to the most mundane of questions, her life as she tells it replete with the kind of wondrous serendipity that makes much of her work so beguiling. It’s no wonder, then, that her debut short story collection, The Necessary Grace to Fall, won the Flannery O’Connor award, nor that her latest novel, The Secret Letters of Velta B, has been lauded by critics—dubbed "a memorable tale" by Publishers Weekly, with Kirkus calling it “an astonishing alchemy of history, romance, and fable.”

It’s a deeply human and at times wildly fabulist story of how one Latvian town negotiates and comes to terms with its identity and troubled past, populated by a cast of compelling, mildly crazy characters all connected to a family of gravediggers. They hold on to their traditions in a time of socio-political change, sing “dainas” on almost all occasions, and eat smoked eel. Which is why it’s so astonishing to learn that this book is Oregon born and made.

Ahead of her reading at Powell’s on July 27, we talked to the Keizer-based Ochsner about her obsession with Latvia, bear-slayers, and the mysterious appearance of a stately gentleman with snow white hair...

The Secret Letters of Velta B is unlike any other book I’ve read this year, particularly from an Oregon author. It feels at once fresh and timeless.

It took about eleven years to write, so I’m glad you said it sounded fresh! It wasn’t feeling very fresh to me the last three years.

So where did a story about a Latvian town mired in traditions and battling with change begin for a Keizer, Oregon resident?

In 2005, I got bit by the Latvian bug. I read a short story by an author who lives in Portland, who’s Latvian—his name is Pauls Toutonghi. He wrote this amazing story that showed up in the Boston Review that year. It was such a striking and compelling story, and it said in the bio that he was Latvian and lived in Oregon. I thought, “I have to find more work written by Latvians, and more work about Latvia!”

So I ran down to the local independent bookstore in Salem. I talked to the woman behind the counter and I was probably foaming at the mouth because I was so excited. I said ‘You’ve got to help me find anything written about Latvia, and anything written about Latvia, or Americans who are Latvian writing about Latvia!’ Her eyes got really big and she said, ‘That’s so strange! Nobody comes in here asking about Latvia.’ I said ‘Well, can you help me?’ And she pointed to her name tag. Her name was Dace, and she said, ‘I think I can, because I’m Latvian’. It was one of those wonderful miraculous moments, and that began our friendship through which she began teaching me the Latvian language, and telling me her family story, how she grew up in a displaced person’s camp in Germany before her family was sponsored and came to the states and settled in Minnesota.

Did you visit Latvia to research the book?

One of the thing Dace said to me in about year number two in our progress through Latvian history and culture was, ‘Gina, you have to go to Riga. And then when you go to Riga you have to go stand in the river. And then when you stand in the river you have to bring back some rocks and some mud in this little vial.’ And she handed me the vial. So that began a series of trips to Latvia and Riga in particular and I did bring her back some river mud.

From that experience I realized how very connected to the land, to the earth, to the ground, and the water, people are, and how important that is to preserve and how important it is to their Latvian identity.

That sounds like an unorthodox way to happen upon a story. Is that your usual methodology?

I sort of Forrest Gump my way through things. I often don’t have a concrete plan. If I was an anthropologist or an ethnologist, I would flunk. It’s very poor methodology to just go out there and hope something happens. Yet that’s the way it happened for me and has happened for me with everything I’ve done. Once I got to Latvia I was hopelessly lost and a man appeared out of nowhere, a very tall, very stately looking gentleman with snow white hair. He said, 'You look lost, I think I can help you. I’m a rather important person. I’m the cultural attaché for Latvia from Sweden, and if you follow me to my limo I’ll take you wherever you need to go.'

That started a whole other wild series of meetings with artists and survivors and Gulag camps and poet laureates. It’s wild how people come to the rescue of a very lost person. That’s my methodology—I just go and trust that something will happen when I get there. And it did.

Wannabe writers are often told that they should write what they know, tell their own story. Yet you’ve pretty much blown through that rule. Were you at all hesitant to write about a country and culture with which you had no initial personal connection?

I was very concerned, very. I asked Dace regularly, ‘Do I have the right to write this story? Is it OK that I’m not Latvian and I’m writing about Latvia?' And she said, ‘Gina, two things you have to remember: Latvians like to argue and you’re not going to please everyone and there’s going to be lots of Latvians that don’t like that you’re writing this. Secondly, you have to write this story because no one else is doing it right now. I’m giving you permission to write my family’s story. You have to write this.’

If people only wrote what they really feel like they knew, we’d have very little being written, because the individual story is a limited, narrow little tract, and I’d have nothing to write about. I could see why someone would say, ‘Then you shouldn’t be writing.’ But my goal is to find the thematic strands that apply to us all, that have a universal message that would be true for anyone reading this.

There are subjects you treat that apply to countless other places in the world, and much that feels like it has resonance for what’s happening here now. I’m talking about how the characters grapple with the notion of ownership of a nation, and who belongs there. Their talk of 'Latvians for Latvians' has within it a sentiment not too far from 'Make America great again.'

My hope is that anybody could read it, whether they know a thing about Latvia or even care to know about Latvia. They would read this and say ‘yep, this is just like where I live. There are things about this that remind me of people I know.’

How much of you or your own experience went in there?

I’m not Latvian, my parents did not grow up in a displaced persons camp, but some of the characters are composites of people I know and are family members, and some of their experiences I would give to these characters.

I put quite a bit into the narrator because I wasn’t married when I had my son, and I was reliving that whole experience when I was writing [the narrator] Inara’s journey during that year, when she’s pregnant and she has to confess and the family has to finally be OK with it, and then she later does get married. That part parallels my life. And I think my son’s extraordinary, but he has very normal sized ears, I have to say. In fact they’re on the smaller side, actually.

Tell me about those ears! Inara’s son Maris, to whom she’s telling her story, is born with abnormally large, furry, and powerful ears. Where did they come from?

There’s a much beloved story that is told in Latvia, called the bear-slayer story. It’s like the American Paul Bunyan story. It’s this folklore-ish tale about a young man who’s got this incredible strength, and will rise up out of the river and will defend Latvia if Latvia is ever being threatened by a foreign enemy. And the thing about Bear Slayer is that he’s got enormous ears—they look like bears ears, they’re big and furry and sit kind of high on his head—but other than the ears he’s completely human. But he’s got this super human strength. They love to tell the story and it’s a story they did tell during the Soviet occupation, because it gave them hope that in some way they would be able to slay the bear.

It was kind of like a story that rallies everybody under one banner. So it felt natural to work it into the story, and what better way than to have this boy with these ears. People are looking at this kid and thinking he’s going to be something really wonderful. He’s going to be the guy—who knows, maybe the next president of Latvia. And actually, except for his enormous powers of hearing, he’s really quite ordinary. That’s the reversal. But sometimes there is a power in listening—we learn that from him. It’s actually the road to reconciliation in a lot of ways, it’s his ability to listen and hear in an age of a lot of talking.

Do you ever think about setting stories in Oregon?

I intentionally wanted to set some things in Oregon and explore the turn of the century, the Astoria, Warrenton seaside area in particular. Lots of really creepy things happened and there are a ton of ghost stories and lots of superstitious old wives’ tale type of stuff, so I do have about ten short stories and I’ve just mentally dubbed them 'the creepy stories', and they’re set in Oregon. I do love to write about Oregon, but I have not teased anything out into novel form. That may change soon, I may find a way to connect some of these characters in these stories and create something larger. There’s something about the north coast in particular that’s a little bit eerie, and the more digging I do in the history of the area, the creepier it gets! So I have had a lot of fun with that, and a lot of fun exploring the Finnish and Norweigan population that came out there and was quite robust for some time in Astoria, and all the ethnic tension there.

I am always looking for the next location or the next thematic tangle that I want to explore. Lately I’ve been researching Roma in the Northwest, in particular the Machvaya Roma gypsies, that live in Seattle, Spokane and Northern California, so that’s been interesting. Who knows? I also did five trips to Romania and Bulgaria and lived with some families who are Roma, and wow, that’s an interesting life. And somehow, I don’t now how, but somehow there’ll be a connection between the two locations, so we’ll see.

Gina Ochsner reads at Powell’s City of Books on Wednesday, July 27.