Portland’s Indie Print Mecca Must Move—Again. Can the IPRC Survive?

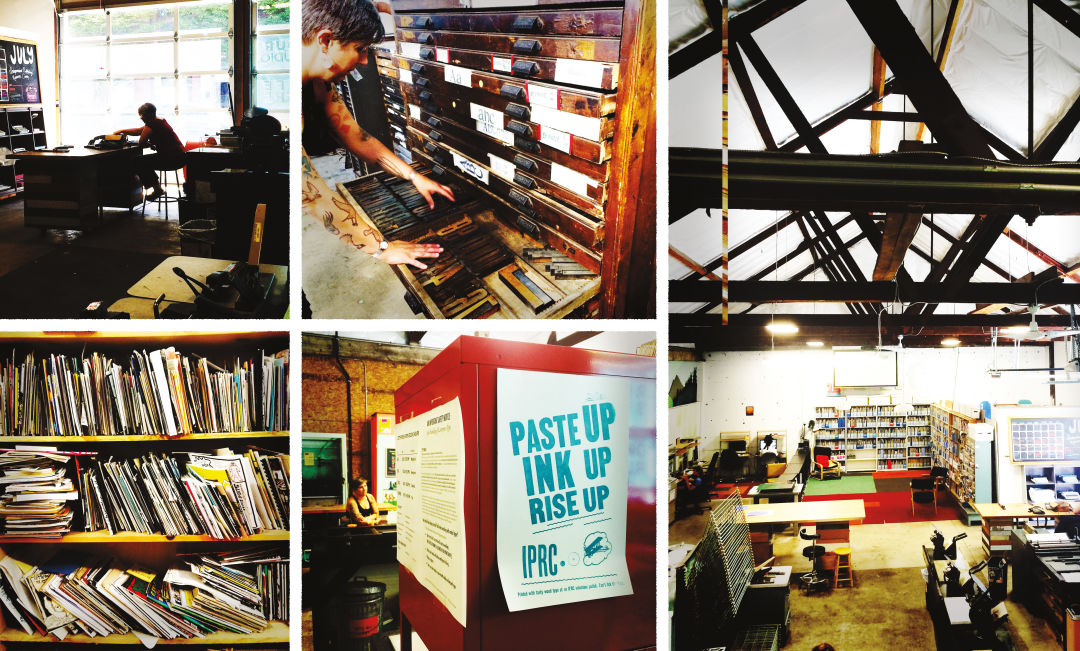

Image: Amy Martin

Click. Clack. Click. Clack. Clickclackclickclackclick.

The Independent Publishing Resource Center (IPRC) sounds like a 1950s secretarial pool one Saturday night, as more than a dozen people hammer away on vintage typewriters, carriage returns ringing. Words clatter into existence, a mechanical storm of creativity prompted by a writing challenge called 1,000 Words. This “type-and-share” is just one of scores of events the IPRC stages in a 3,700-square-foot former solar panel warehouse on Southeast Division, where it also hosts collage nights, zine symposia, readings, book launches, and more.

Since its founding in 1998 by Reading Frenzy’s Chloe Eudaly—a current City Council candidate—and Stumptown Printers’ Rebecca Gilbert, the IPRC has served as Portland’s crossroads of independent publishing, a place to learn printing, bookbinding, screen-printing, graphic design, and allied arts. It’s home to a gigantic library of underground zines (more than 12,000), and counts among its successes a prison writing program launched in 2012 and its four-track Certificate Program, a popular, cheap, productivity-oriented alternative to traditional MFAs.

Michael Heald, a Certificate Program alum who went on to start Perfect Day Publishing—a thriving small press he says might not have been possible without the IPRC—uses the center for book design and feedback from fellow members. “I like the collective effort that you feel part of when you’re in the IPRC,” he says. “The fact that you’re able to put out great-looking work from the stuff that’s there is empowering for all kinds of people.”

Last spring, the IPRC got word that the $2,700-a-month rent on the Division Street warehouse it moved to in 2012 was set to rise by 300 percent. The news broke in April, during A.M. O’Malley’s first week as executive director. O’Malley, formerly the outreach coodinator and then the center’s program director, has been at the IPRC for nine years. It’s been a period of growth to the current paying membership of some 3,000, each paying $6 a month for access to the center’s computer lab, photocopiers, paper cutters, letterpress studio, screenprinting studio, and sundry other supplies.

All of which is at stake as the center finds itself among the myriad of small to midsize arts organizations—Conduit Dance, Shaking the Tree Theatre, and Polaris Dance Theatre among them—displaced from their spaces in recent years in a real estate boom that leaves little room for the kind of hand-to-mouth operations that have long underpinned Portland culture. If the IPRC wants to stay relatively central to the city, says O’Malley, it faces a rent hike of at least 100 percent. “We came to this neighborhood when it was on its way but not quite where it is now,” she says. “This is what happens with artists—they’re the first wave and then they get pushed out.”

To help fund the inevitable move to whatever new lodgings the IPRC secures—the costs of renovating a new space, moving the heavy 1930s letterpresses, lead letter–filled filing cabinets, and thousands of zines—the center has been on a fundraising drive, reaching a $20,000 goal in August. O’Malley says the real cost of moving will be twice that.

“We’ve provided services to tens of thousands of people,” she says. “If each gave us a dollar, we’d be fine.”

Among those tens of thousands of people who have passed through its doors are some of today’s local heavy literary hitters: the center’s former Executive Director Justin Hocking namechecks poet Matthew Dickman, writer Miranda July, Decemberists front man and author Colin Meloy, and children’s book writer and illustrator Carson Ellis.

Ellis says she brought her teenage drawing students there for a tour. “I think it’s a wonderful, critical resource,” she says. “It opened a lot of minds—the resources, the library, the community, the endless self-publishing possibilities. It always meant a lot to them and I wished there had been something like that in my town when I was a miserable teenager. I think it would’ve changed my life.”

Miserable teenagers of the future, be warned. Whatever happens, it’s clear that the IPRC will have to adapt if it wants to survive. With that in mind, changes are already afoot. The honor system long used for payment for photocopies and other incidentals has to go, and prices—including for IPRC membership—will rise to accommodate rising costs. “We’ve been very scrappy and DIY,” says O’Malley. “It’s what people love about the IPRC because it’s very ‘old Portland’ in that way. But we have to get more savvy.”

As the center is forced into change by a changing city, Hocking believes it can survive. His optimism comes with a warning, however, to all who value the creative landscape. “I think if the IPRC was to go away, it would be a tragedy,” he says, “and honestly a place I don’t want to live in anymore.”