Sex, Drugs, and Masterful Movies: Rome's Sweet 1950s Life

Image: Vincent Levy

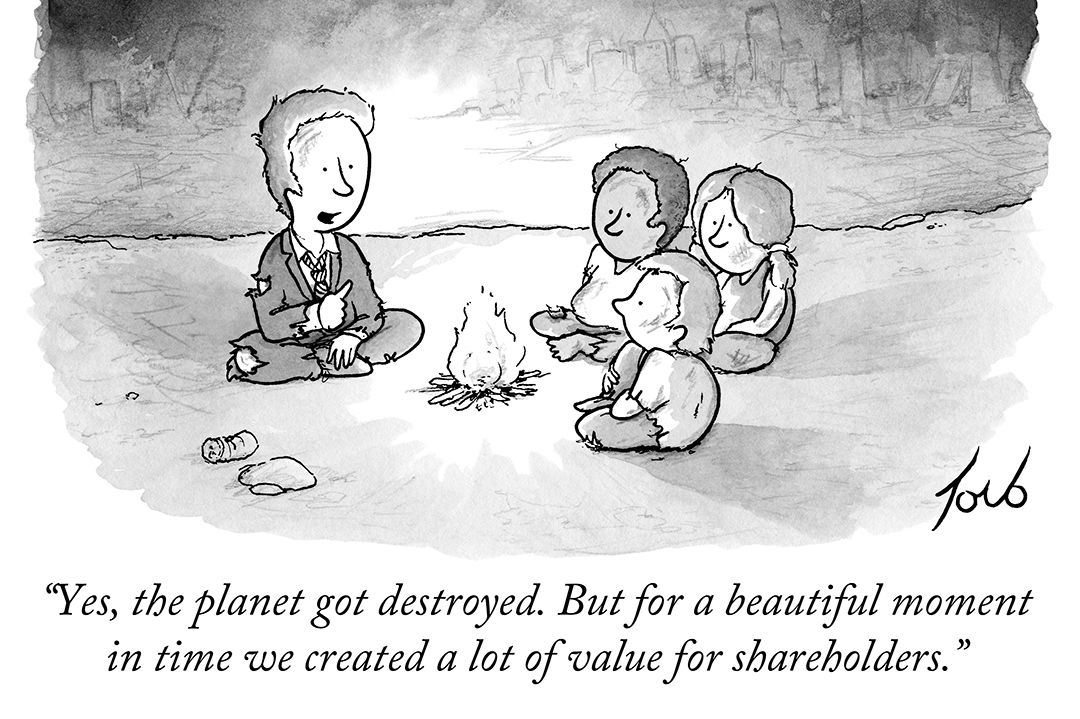

Aristocratic playboys. Race car drivers. Sophia Loren. Late night parties and paparazzi. A deposed Egyptian king. A dead body washing up on shore, a restaurant striptease, a cool-down in a public fountain. Rome in the 1950s had it all—and Federico Fellini, one of the world’s master filmmakers, who encapsulated the heady, star-charged life in his classic 1960 movie La Dolce Vita.

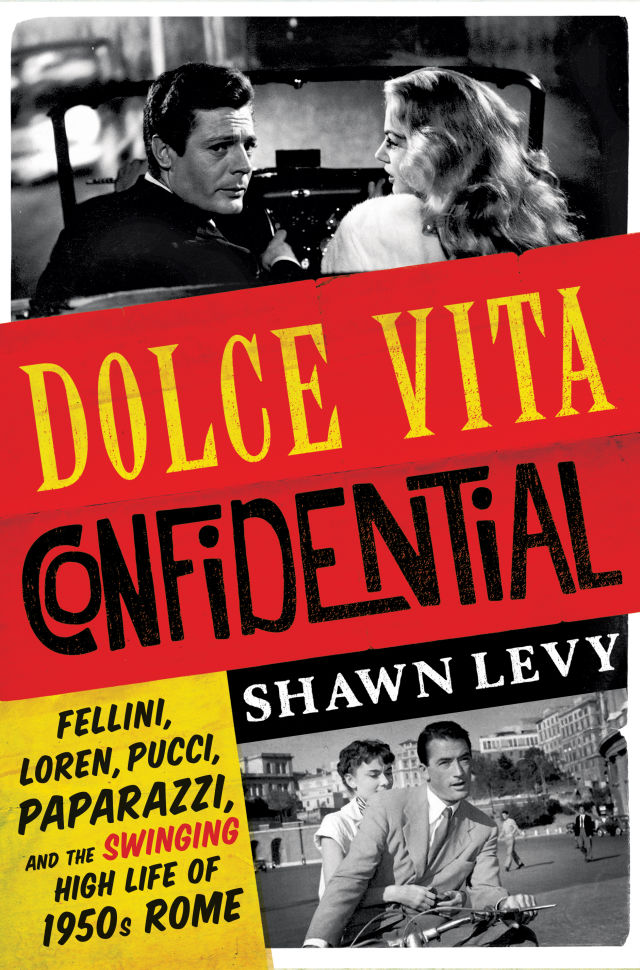

Portland writer Shawn Levy paints a detailed picture of that time in his latest book Dolce Vita Confidential, from paparazzi altercations with the stars to the rise of Italian fashion to America’s love affair with Italian cinema. Ahead of his Powell’s reading on Monday, October 17, the former Oregonian film critic explains how that moment in an ancient city kickstarted our celebrity-saturated modernity.

You’ve written about Paul Newman, Robert DeNiro, Jerry Lewis, and the Rat Pack, among other subjects. Why the choice to move to 1950s Rome?

It’s absolutely the sexiest topic I could think of. And I was asking myself, how far back can you go to get to a moment that looks like today? You can say Berlin in the '30s, the lifestyle, but they didn’t have the media. Or Paris in the '50s, there was a certain style, but it wasn’t pop culture. One of the defining characteristics of our day is that we’re in nonstop pop culture. And in Rome you had the fashion, you had the cinema, you had the tabloid media, you had the scandals, and you had these photographers. It seems to me that even more than radio, television, or cinema, the tabloid photographers had the ability to make a sensation or make someone a celebrity for doing nothing. That’s the world we live in.

So [1950s Rome] is sort of like the first supernova burst of modern culture, and it had Fellini. And Fellini might be my first love as a filmmaker.

Fellini’s La Dolce Vita—a Palme d'Or and Academy Award winner —is the climax towards which your book builds...

The film is the hero in a weird way, the apotheosis of the whole decade that preceded it.

And defines it.

It defines it, it critiques it, and it includes it. Because you had all these people on the scene the Romans would have recognized—the painters, the barflies, the hedonists, the nobles, actually playing themselves. If you saw it in Rome in 1959 you would have been scandalized because this was the stuff you didn’t tell your vanilla friends or your mother that you did. And here it is on screen, and on the one hand it’s incredibly glamorous and beautiful and people wanted to live La Dolce Vita. On the other hand, it’s completely rancid and venal and you see everything that’s wrong.

You talk about the scene at the end of the film where a dead fish appears on the shore, and how for many that was a metaphor for the death of Roma Montesi, a young woman whose body washed ashore in 1953. That event ignited investigations that became the talk of the city, with allegations of sex orgies and drugs, and high-profile figures involved.

Everyone in Italy would have seen it that way. The way that in 1999 if you filmed a white SUV going slowly on a freeway, every American would have thought of OJ Simpson. It’s a brilliant metaphor, and you know what he’s talking about, but for Italians this was bigger than that—this was the crime of the century for them, right there, on the screen.

The film elicited quite a reaction, one that surprised even the filmmaker.

Even his fellow filmmakers, the aristocrats (Vittorio) De Sica and (Luchino) Visconti, sort of snubbed the film because they thought, well, this is a housemaid peeking through a keyhole, this is someone who doesn’t have a valet telling us what a valet is like. But there was also this sense of airing dirty laundry for the world to see, and then being celebrated for it.

So how do you go about living in Portland in the early 21st century and writing about Rome, 70 years go?

Well, you gather materials as they become available. There are a couple of books I relied heavily on that I had started eBay searches for in 2002 and once a year, an item would come up. So it’s partly gathering materials. It’s partly selecting. There are plenty of people left out of this book, plenty of films that only get a passing mention. You can’t include it all, so you choose the ones that are rich in resources.

And presumably you had to visit the city itself.

Yes, they twisted my arm and sent me—they made me eat the food, it was terrible! I spent three weeks in Rome in late 2014, and I used the national library, the national film archive, the Cineteca Nazionale and its archives, and a couple of specialty film book stores there. And then a big part of this book was just walking the territory. I was like, okay. If Fellini lived here, and this was his favorite restaurant, then every time he went out to dinner he would have passed this bookstore, and the bookstore is no longer there, but in my mind it is. I transpose a map of 1955 onto 2014 and see Rome. So you could see, well, this really was a cluster, these were the hotels where the celebrities stayed, these were the newsrooms of the tabloid newspapers, these are the ateliers of the fashion designers. I’d look on it on a map and connect things.

Did you have to watch a lot of movies?

Image: W.W. Norton

I probably watched 60 odd films. Which is one of the great things about writing books. You asked how you do this in Portland: Multnomah County Library inter-library loan, they’ll get you anything! And Powell’s—when I did a book on a Dominican playboy, there was a shelf of books on Dominican Republic history, at Powell’s. I’m from New York City—the Strand does not have that shelf! I know Foyle’s in London really well—they do not have that shelf. Powell’s has that shelf. And the third leg in the troika is Movie Madness. Once in every book [I write] I find something that Movie Madness can’t get and I’m almost happy, it’s like ah! They’re not infallible.

I watched La Dolce Vita two or three times, so that makes probably a dozen times I’ve seen the film in my whole life. But even so, as I was writing I would go back and look at certain moments I couldn’t remember. In my mind, Marcello and Sylvia kissed in the fountain. But they never do. There’s an orgy, he sleeps with Maddalena in the prostitute's bed, he's got a girlfriend who tries to take her own life to get his attention, so there’s sex all over the place, but not with her.

When it comes to structuring the book, you begin with the paparazzi. Why?

They’re the novelty. We have fashion in Paris, menswear in London, a textile garment business in New York, we have movie making in California and Berlin and Paris and London, but nothing like these [photographers] had ever existed. There was never the phenomenon of a pack of photographers, chasing down and instigating incidents with famous people.

They ended up being a central part of the film too. There’s a famous scene you describe in the book, where Steiner, the intellectual, has just killed himself and his children, and his wife is on her way home, not yet aware of what’s happened, and is accosted by these photographers.

Now when I see the movie, probably that’s the most disturbing scene. This woman is coming home and is going to find out that her husband has killed her children and himself, and the paparazzi are surrounding her. She’s a beautiful woman, she’s coming home with her shopping, and she’s like, “Oh, you’re mistaking me for an actress.” And the policeman is saying, “Guys, c’mon, show some decency,” and they don’t even listen. That’s more disturbing to me than anything in the film, and it’s exactly where we are today. It’s exactly where we are today. Those guys kicked that door open.

Shawn Levy reads from Dolce Vita Confidential at Powell's on Monday, October 17.