Portland’s Cultural Exports Might Never Take Over the World. Here’s Why That’s a Good Thing.

Search your mind for Portland’s biggest contributions to pop culture. You might find yourself stymied. Our town boasts many great moviemakers and musicians and comic book artists and such. But we don’t really have a signature creation: a globally acknowledged super-hit that people who can’t find Oregon on a map think of, the way The Wire conjures Baltimore or Breaking Bad is synonymous with Albuquerque.

In fact, it could simply be that Portland doesn’t do pop culture—that there’s something essentially Portlandish in an aversion to appealing to the masses everywhere. One doesn’t, in short, live here to declare oneself to the world. One lives here to drop out of the rat race, do one’s thing, and perhaps, keep a sly hand in the mix. Pop culture, the lingua franca of modernity, gets made here despite our characteristic civic discomfort with ambition. From Dark Horse Comics in Milwaukie to Todd Haynes’s bungalow in Northeast Portland, we produce it—and are known by it, at least in some circles, whether we care for that renown or not. But the world doesn’t yet have a shorthand way to pigeonhole Portland, the way Nashville is a synonym for an entire music industry, or how Rocky will run the streets of Philly forever.

Instead, Portland’s select brushes with pop culture success are more like a secret code to figuring out what the city is all about.

We’ll get to our Bizarro World simulacrum, Portlandia, in a bit, partly because its hipsters, neurotics, freaks, and nitwits could live in any trend-drunk spot on earth: Silver Lake or Williamsburg or Austin or Camden Town. What, then, are Portland’s defining popular culture products? What films, songs, and TV shows do new arrivals think of as their planes descend toward PDX?

The truth is, it depends on which Portland you’re talking about. If you mean the increasingly legendary “Old Portland,” America’s introverted wallflower cousin, the pickings are slim. Until the mid-’80s, Portland produced only one bit of pop that migrated out into the world to make a name for itself—the frat-rock classic “Louie, Louie,” recorded in 1963 by two local bands, the Kingsmen and Paul Revere and the Raiders. Those three minutes of catchy nonsense are immortal, but not original. (The composer, Richard Berry, first recorded the song in 1957, in Los Angeles.) And though it’s still the best-known gift Portland has ever given the world of rock, few know it came from here.

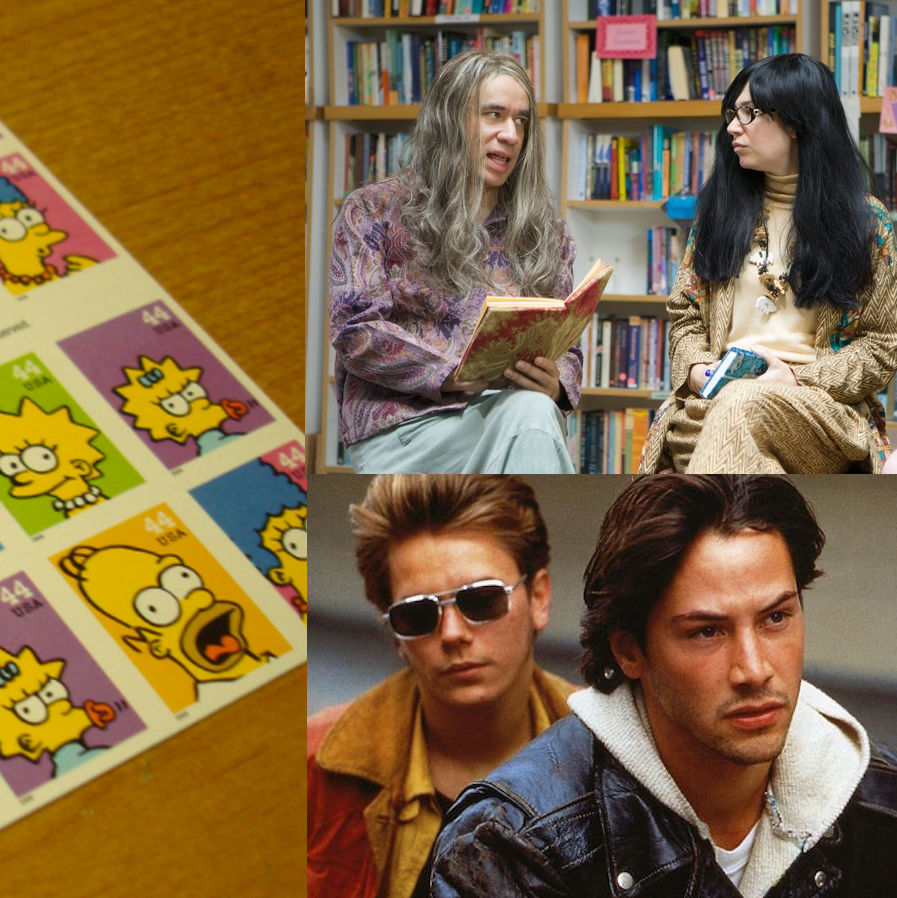

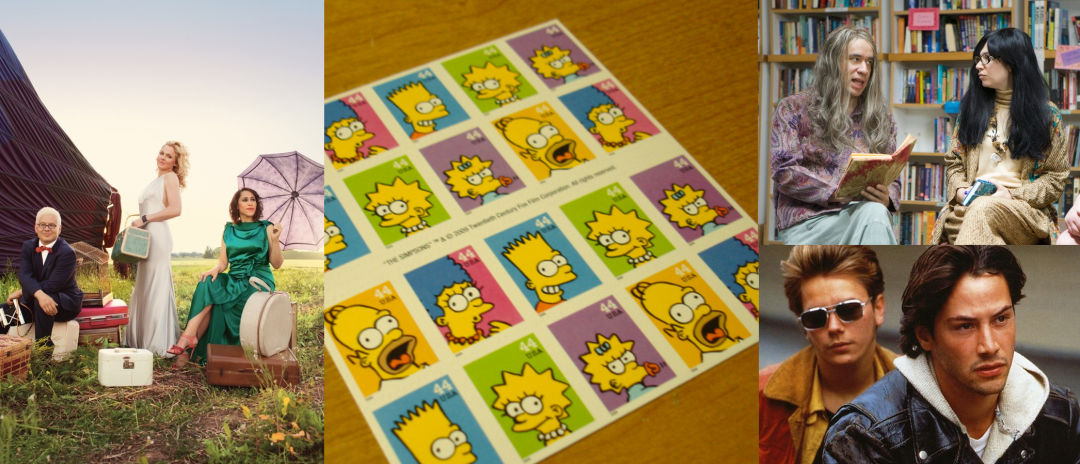

A quarter century passed before anything else came close, and that was something that also, typically, concealed the Portland strain in its veins. The California Raisins enjoyed a burst of fame in the ’80s: commercials, four albums, a TV series, and Dumpsters’ worth of merchandise. But there was a catch: Although the little purple rascals were created by Will Vinton Studios of Northwest Portland, they had nothing to do with Portland by design. Their success funded a lot of great animation here, but they, deliberately, weren’t from here. This wasn’t unusual. In fact, the most famous work of animation with roots here also camouflaged its Portland DNA. The Simpsons, created by Lincoln High School grad Matt Groening, debuted in 1989 and was filled with Portland signifiers, especially in the names of its characters: Quimby, Terwilliger, Flanders, and so on. But Groening had moved on to Los Angeles before its creation, and the show’s very premise was to portray a kind of American Everytown, so we can’t really call the Simpson clan true Portlanders (though namesake town Springfield, 100 miles to our south, might have a better claim).

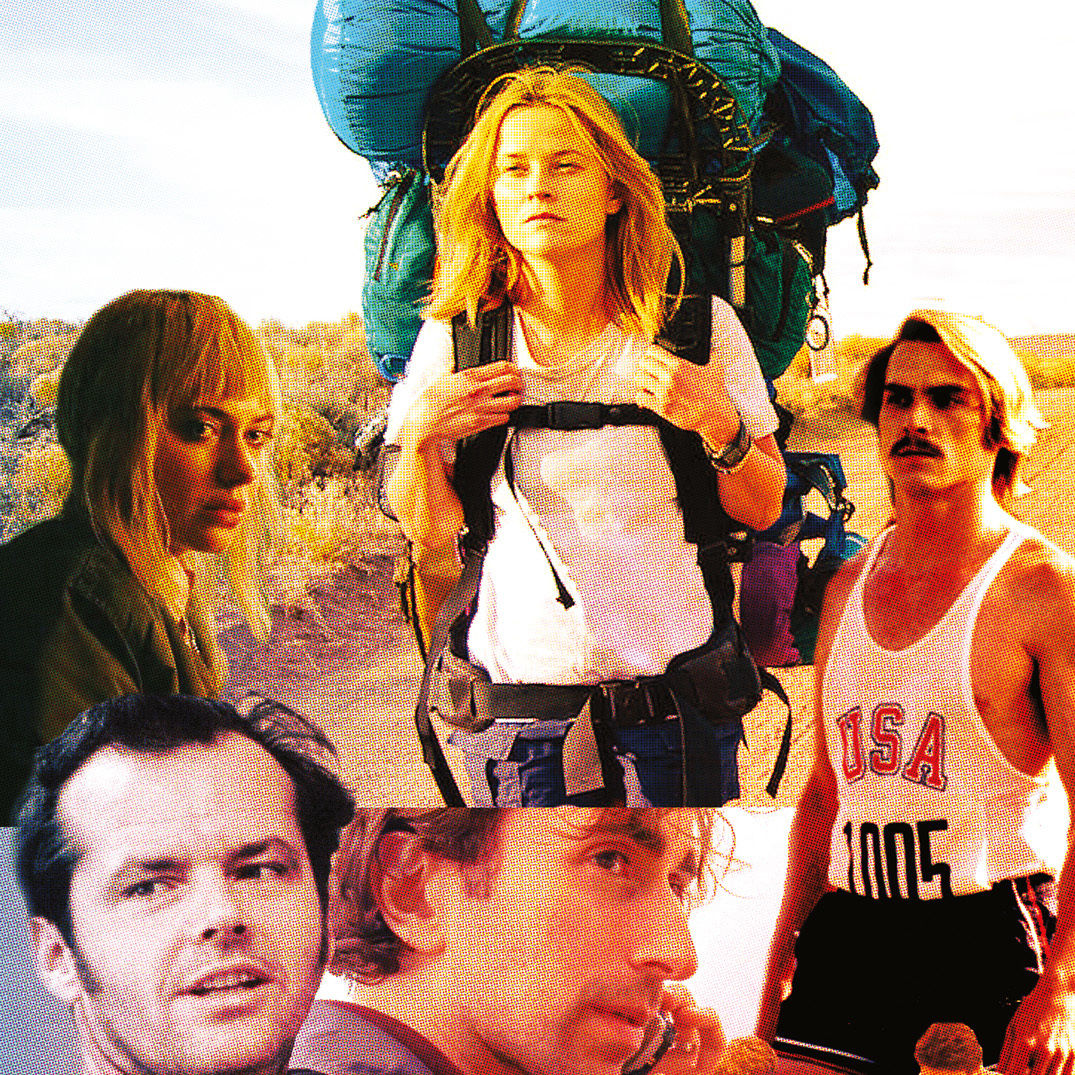

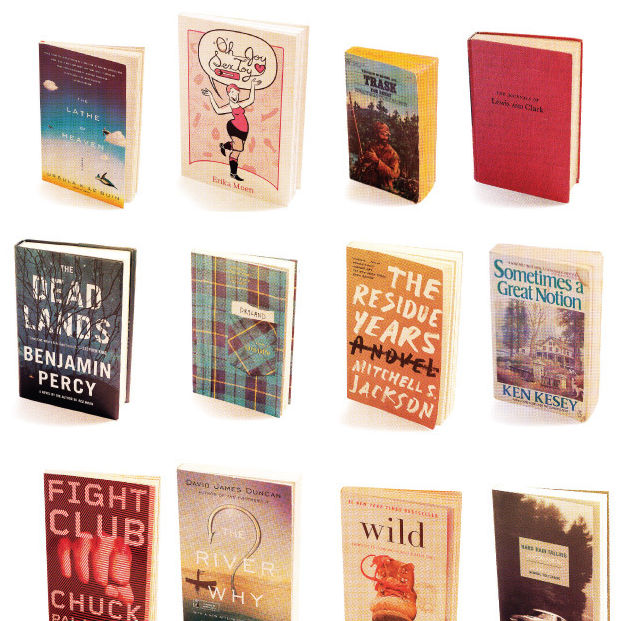

A true product of our cultural terroir appeared that same year, though: Drugstore Cowboy, the second feature film by Catlin Gabel grad Gus Van Sant. Along with his debut, 1985’s Mala Noche, Drugstore Cowboy serves now as a priceless time capsule of a mostly vanished city of grit and abandonment: the SRO hotels, the greasy-spoon diners, the ungentrified warehouse-lined streets that hadn’t yet become the Pearl District, the air of gloom and listlessness and hand-to-mouth living. Van Sant was the perfect artist for that moment, when Portland was still woozy from the economic meltdowns of the ’70s and ’80s but was also incubating a quiet, potent counterculture. His work was low-key, intimate, frank. And critics loved Drugstore Cowboy and its follow-up, 1991’s similarly grungy My Own Private Idaho.

But Van Sant didn’t suddenly turn Portland into a recognizable font of culture. He went on to bigger films—To Die For, Good Will Hunting, Finding Forrester, Milk—but they were all made elsewhere. Conversely, his Portland films—Elephant, Paranoid Park, Restless—have been low-budget, almost experimental works. And even his early successes were overshadowed by a concurrent project to the north—Twin Peaks, made by Missoula-born David Lynch, shot near Seattle, and far more influential in its moment than anything Portland has ever produced.

Then came the slew of best-forgotten movies such as Dr. Giggles, Frozen Assets, Body of Evidence, and The Temp, and short-lived prime-time shows like Nowhere Man and Under Suspicion. The one Oregon production of the time that had commercial punch, 1993’s Free Willy, was (like the state’s most successful contribution to ’80s cinema, The Goonies) mainly shot at the coast.

Meanwhile, musically, the ’90s were very rich for Portland, with the likes of Elliott Smith, Everclear, the Dandy Warhols, and Meredith Brooks all breaking big, and others such as Dead Moon, Pond, Hazel, and Heatmiser earning local legend status. We loved ’em all (well, mostly) and rightly so, but none hit the world remotely as hard as the bands that emerged from Seattle at the same time: Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, etc. Portland musicians recorded hits (“Bitch,” “Bohemian Like You”) and even an Oscar nominee (“Miss Misery”), but the bands themselves never became iconic. This set a pattern: our biggest successes in music have been in the niche world of indie rock, a microcosm big enough to make bands like the Shins, the Decemberists, and Sleater-Kinney into stars but not, like, real stars. And none of them ever released anything as big as “Smells Like Teen Spirit” or “Baby Got Back.”

That’s kind of how it’s always been: Portland does bespoke, indie, but not megafamous or world-beating or, sadly for artists (unless you’re Pink Martini), particularly profitable. Even in this moment of our Portlandia-driven ascendancy, we’re kind of embarrassed, even annoyed with our success.

We seem temperamentally ill-suited for this kind of thing. Our native recalcitrance probably engenders the biggest gripe some folks have with Portlandia. Unlike the TV series Grimm, Leverage, and The Librarians, or any of the indie films that have been shot here recently, Portlandia purports to present us to the world as we are (with, granted, the distortion involved in satire). We nitpick about specific details of Portlandness, or grouse that it distorts us or that it’s not all that funny or that it has harmfully altered our daily experience of the city.

But I suspect that the main reason Portlanders complain about Portlandia is that it’s a hit. It takes the things that are here all around us and alchemizes them into something about us that the rest of the world recognizes, appreciates, and wants more of. And, I say with love, that’s not something we like all that much. This is a town where the top tourist attractions include a bookstore and a rose garden, for Pete’s sake. When we make things, we make things for ourselves first.

It makes for a nicely low-key way of living, but it’s hardly a recipe for world domination. It is, however, how Portland does pop: locavore, DIY, and cool only until the rest of the world grows too fond of it.