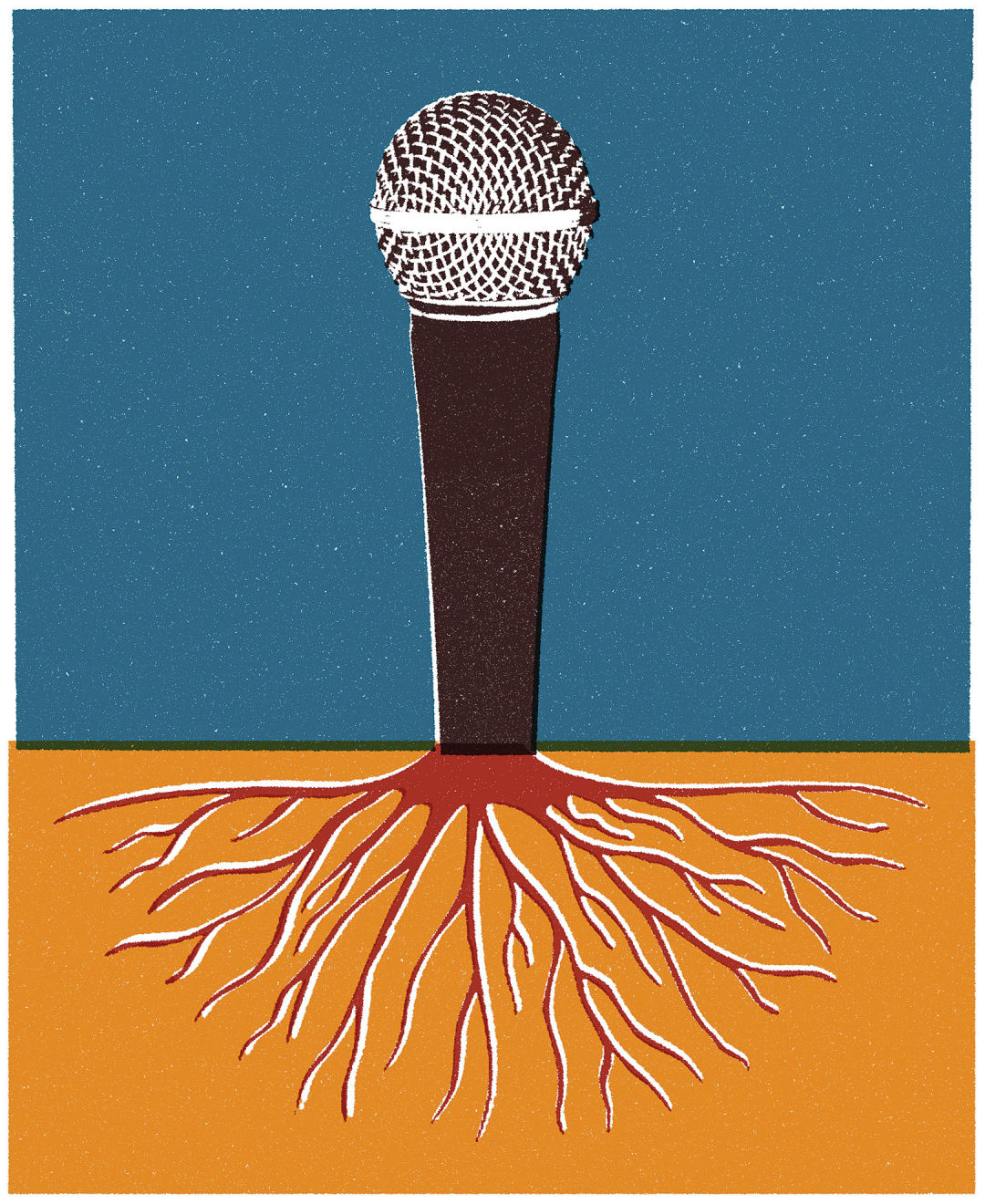

Why We Need Portland’s Burgeoning Hip-Hop Scene Now More Than Ever

Image: Matt Chase

It was a hot night in June. As I arrived at the Hawthorne Theater, a youthful crowd was already crammed in for the hip-hop showcase TNO Presents, clamoring to buy gear from artists hanging out at the merch booth. As a retired local rapper and longtime editor of an online hip-hop magazine covering the Northwest scene, I was surprised by the enthusiasm for an all-local rap show starring no clearly established acts.

“The excitement around these younger guys is unbelievable,” says DeAndre Woods, a 23-year-old CEO of Trust No One Entertainment, which curates this buzzing, all-ages concert series that typically sells around 300 tickets.

The night’s excitement for homegrown hip-hop acts captured the broader energy that’s boosting Portland’s scene right now. There’s an ethic of teamwork and collaboration, as opposed to a culture of division and stagnation that some think dominated Portland’s hip-hop world in the past.

“There’s a lot less eyeballing and hating,” notes rapper and Northeast Portland native Donte Thomas, 22, on the intro to his August 2016 album, Grayscale. “When you hear that someone else is doing something from Portland, you get more excited, [rather] than being like, ‘Oh, that should be me,’ you know?”

Predictions about the rise of Portland hip-hop have been made before, of course. But these days the hype seems real, tangible, and riding a wave of young talent. This summer, Aminé, 22, racked up over 19 million YouTube views—and twice that many streams on Spotify—for the catchy, playful “Caroline.” University of Oregon graduate Chris Lee, 22, grabbed more than 200,000 views for his “Lemonade” series. Young artists like Heff and Thomas are commanding thousands of video hits and streaming music plays regularly. Meanwhile, collectives such as SQD, STRAY, L$P, Gutter Family, and the Eastsiders—most of whose members are in their teens or early twenties—are banding together to cultivate significant fan bases.

“They are grasping onto the concept of quality—from production, to the image they put out, and how they handle business,” says Woods. “The younger wave is [using] iTunes, Pandora, or Spotify to go beyond Portland.”

Portland has an infamously tense history with hip-hop. In March 2014—to cite one example that has gone down in the lore of the local scene—Portland police shut down a show at the Blue Monk in Southeast, citing capacity concerns. The final scheduled performer, veteran battle-rapper Illmaculate, vowed on Twitter to never perform in Portland again “as long as the blatant targeting of Black culture and minorities congregating is acceptable common practice.”

The venue closed for good shortly thereafter, and the name “Blue Monk,” for many, became synonymous with the city’s hostile treatment of hip-hop shows. Making matters worse, in May 2015 St. Johns rapper Glenn Waco, 24, and a friend were arrested at Last Thursday on NE Alberta while providing aid to a shooting victim, in what many saw as police retaliation. The event brought newfound solidarity. Waco, a de facto leader of Don’t Shoot Portland, a group born of the Ferguson protests in 2014, helped shut down a city council session this fall over concerns about police training. Music and activism intertwined.

Superstars have helped legitimize the underground. Last summer, popular nightclub Holocene hosted the launch party for NBA player-turned-rap mogul Martell Webster’s indie music label, Eyrst, which employs a number of promising local artists, like the psychedelic Last Artful, Dodgr. Holocene also worked with Waco the following month to bring out Trail Blazer superstar Damian Lillard—a respected rapper himself who encourages his fans to write their own rhymes in his popular weekly Instagram competition, @4BarFriday—for his first live performance. (Lillard sold out the Crystal Ballroom for another show this year and just dropped his full-length debut.) And for the last three years, even PDX Pop Now!, the long-running annual festival largely associated with indie rock, has highlighted many rap artists.

“I feel like as soon as I moved, Portland started to crack,” says Tope, a longtime local artist now in Los Angeles. “You have to give credit to Damian Lillard, CJ McCollum, and some of the local celebrities that have been coming out to events because they definitely add a legitimacy factor that may have been missing in the past.”

Still, not everyone is proclaiming a hip-hop golden age just yet. Longtime Portland MC and event producer Idris “Starchile” O’Ferrall, 41, who hosts the hip-hop concert series Mic Check, is cautiously optimistic.

“Social media is one of the best and worst things to happen to music. The traditional paths to ‘getting on’ are no longer the only ways to be heard. Now anybody can make music and put it on Soundcloud, but the question remains, will people show up to support these artists?” he says. “It’s a matter of seeing what will happen going forward. We’ve been here before with U-Crew, Lifesavas, and Cool Nutz. Hopefully this new wave can go even further. The Internet makes that easier.”

Last October, Mayor Charlie Hales unexpectedly proclaimed an annual Hip-Hop Day, recognizing a few of the city’s highest profile artists—the St. Johns–born Mic Capes, Jon Belz, and Vinnie Dewayne—with a concert outside Portland City Hall. The reaction in the hip-hop community was mixed, but the move was taken as a good-faith gesture. But the truth is hip-hop had already won. The question is, just how high will it go?