Why You Should See This Show about Rodney King (Before It Hits Netflix)

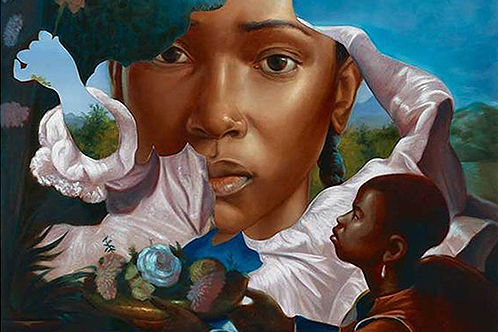

Scene from Rodney King with Roger Guenveur Smith

Image: Patti McGuire

This month marks 25 years since four LAPD officers were acquitted for their part in the brutal beating of Rodney King, a verdict that sparked riots claiming the lives of more than 50 people. Actor, playwright, and longtime Spike Lee collaborator Roger Guenveur Smith explores the story of what he calls “the first reality TV star” in his one-man show Rodney King. It’s been acclaimed as “sinuous, complicated, deeply moving” and “intensely cathartic,” and has played in theaters all over the country and around the world since it first played in LA's Bootleg Theater in 2012. Now Smith ends the piece's four-year-run in Portland, before the work goes onto Netflix in the form of a Spike Lee film, with Smith at the center (watch it online starting Friday, April 28).

We spoke to Smith ahead of his Portland visit—he's at Artists Rep April 21–23—to talk about great American speeches and homophobic raps, the legacy of an ordinary man thrust into the international spotlight, and why this town at this time is an interesting place to end the show’s long run.

Why did you decide to explore the story of Rodney King so many years after he became a household name?

In June of 2012, I was actually contemplating doing a piece on Otto Frank, the father of Anne Frank, and his journey, which was a really fascinating one. And lo and behold on Father’s Day, of all days, I opened up my laptop and found that Rodney King had expired in his backyard swimming pool, and I felt a very deep sense of loss, as if I had lost my own brother. It became clear to me that I had to at least do something for that season of mourning, to try to figure out for myself why Rodney King mattered to me and why potentially he would matter to my audience. By the time the first week of August came around I was on stage at my home theater, Bootleg Theater here in Los Angeles, trying to work it out.

How did it evolve from there?

I thought it was simply going to be a kind of intimate memorial meditation for that particular season, but for whatever reason, the story continued to resonate in the country’s imagination as the country devolved into a series of highly publicized tragic events.

Though you’ve delved into historical moments and characters before in your work, you took a different approach with the Rodney King story.

I wanted to proceed with a certain expedience with this work because I imagined it as a memorial in a sense, so it wasn’t going to be a years-long jumping into the Rodney King archives. I also wanted to maintain the position of the outsider. I wanted my resources to be the same resources as anyone who could open up their laptop and Google "Rodney King."

I relied upon stuff that was in the public domain. And also when Rodney King died, there was very strong contention within the family and I certainly did not want to step into that.

How did the piece come together for you?

I knew that the bookends of the piece would be firstly Rodney King’s speech, which he delivered May Day, 1992. I think it’s one of the great American speeches, I really do. It was delivered under great pressure, he was probably drunk, he was hot, he was disappointed, he was traumatized, he was brain-damaged, and to be able to pull it together like that and to deliver a speech with such conviction and passion and effect—because in a sense he stopped the riot. And that other King, who gave some pretty good speeches, he never stopped a riot. He proscribed the cause of the riot but he never stopped one.

Rodney King certainly could have gotten out there and said “burn it down!” and I don’t know if anybody could fault him for saying it, given that the entire world watched these officers beating him on video tape and he had to stand up in that courtroom and listen to multiple not guilty verdicts. And then to see the city explode in his name, to see 50-odd people expire in his name, was a tremendously traumatic experience, and unfortunately that speech has been relegated to a very simple soundbite of “Can we get along, can we all get along?”

That soundbite fails to take into account that he answered that question later in the speech…

He answers the question! I thought that it was essential for me to deliver the speech in its beautiful, disturbing, frustrating entirety, with all those dot dot dots and all those ellipses, and all those things you can tell that he wanted to say but his brain wouldn’t allow him to say—he couldn’t get there. All the malapropisms, all of that, it’s just a beautiful and disturbing and haunting and instructive moment. I’ve been calling it the gospel according to Rodney King.

And I knew I had to deliver some of that great rap by Willie D of the Geto Boys entitled “Fuck Rodney King,” where he lays it out. He says Rodney did not live up to the image of machismo that he needed from Rodney. He thought he was a sellout. It was a homophobic rant, and I quote a couple of verses and that’s how I kick the show off. But in between I improvised what I’ve been calling a post-mortem interrogation of Rodney King, and through that interrogation I’m able to play any number of people who touched Rodney King in some way or who were affected by his story in some way, and I’m able to construct a kind of non-linear biography of Rodney King so that the audience can hopefully understand the man behind the myth. Because I think most people, if they know Rodney King at all, only know him as a human piñata.

You call him the first reality TV star, right?

That’s what I say and I think in a certain way he was.

He became a symbol for oppression and inequality through that one piece of footage.

And in LA at that time there was a girl by the name of Latasha Harlins who was killed in a confrontation with a shopkeeper just two weeks after Rodney King was beaten, and her killing was caught on the security cam in the store where she was killed, and that image then supplanted the image of Rodney King being beaten. These stories became intertwined for the next year–the woman who killed Latasha was convicted of involuntary manslaughter. She never did any jail time and this outraged the community. That was in early April of '92, and then of course in late April of '92 was when the officers [who beat King] were acquitted. These two stories are intertwined and I try to tell that story as well, because I think that historically it's an important thing to understand.

The play has had an incredible run, and travelled the world. Now your performances are nearing an end, though the Netflix film will give it extra life. How do you feel about moving on?

I think it’s the right time. It’s the 25th anniversary of ‘92, and it’s time to move on to other work. This little meditation has expanded far beyond where I thought it would go, taken me to London and Amsterdam and New York several times, and Oakland recently, and Seattle and St. Paul and Chicago and Washington, DC, a couple times and North Carolina, and every place I’ve played has had its own Rodney King story in a sense. It’s enabled communities to rally around this idea not simply of police brutality, which I think is a universal theme—the abuse of state power against the people—but the very fundamental struggle for human survival which Rodney King demonstrated, and I think in an instructive and tragic and sometimes comedic way.

Portland’s show will be the last one, right?

I’m doing the final performance in Portland, which is having its own civic moments, breaking down a homeless camp, a crisis with the police department, multiple issues there, street demonstrations. And there’s the whole history of Oregon. Plus those guys took over federal lands two years ago in the state of Oregon. So it’s an interesting place to conclude the live performances of Rodney King.

What’s the takeaway for you after all this time on this work and on this individual?

From the beginning I’ve been calling this so-called performance a prayer, and I think that the scripture has been provided in large measure by Mr. King, who asks us a really fundamental human question: “Can we, can we, can we all get along, can we get along?” And he does answer his own question. Yes we can, we can get along, we just have to work it out. We’re all stuck here for a while, so let’s work it out.

It’s not a happy story, but I think he has left us a legacy, a kernel of truth and honor and humanity and dignity, for however many minutes he spoke on that day. And if anything, that’s something he has given us which is impeccable and speaks to not simply the American dilemma or the black dilemma, but he speaks to the crisis of human civilization.

Rodney King

7:30 p.m. Fri–Sun and 2 p.m. Sun, Apr 21–23, Artists Repertory Theatre, $15–30