A Year Ago, Armed Occupiers Seized a Wildlife Refuge in Harney County. This Oregonian Was Ready to Join.

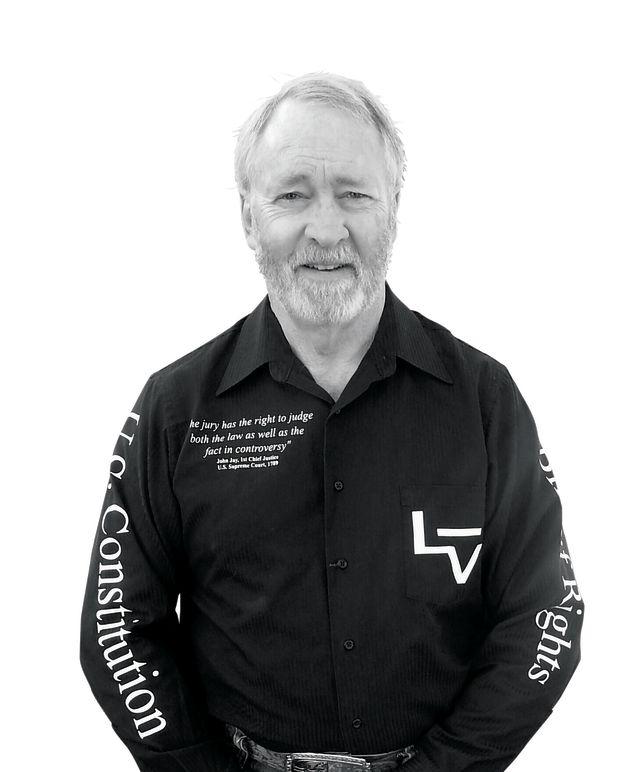

On an achingly cold late-January day in 2016, police officers swarmed Kenneth Medenbach in the parking lot of the only Safeway in Burns, Oregon. The grizzled 62-year-old stood with shoppers unloading carts filled with groceries while officers wrenched his arms into handcuffs behind his back.

He had shown up in the lot behind the wheel of a white pickup bearing royal blue signs reading “Harney County Resource Center.” In his weather-worn Carhartt jacket he looked like just another ruddied, gray-bearded workman from the county, population 7,200. And to some extent, Medenbach did fit into one of Oregon’s most remote and rural areas: he’s a carpenter, a man who builds cabins and knows his way around a chainsaw.

Image: Courtesy Kenneth Medenbach

But he sees himself as something else: an often-lonely crusader, battling the federal government on behalf of his interpretation of the Constitution. His campaign wound through the Northwest’s backwoods and backroads, through every level of courthouse and into headlines, for many years. Two weeks before his arrest at Safeway, he had traveled to Harney County and joined the occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge orchestrated by self-described “Patriot” activist Ammon Bundy. Part of a Nevada ranch family that had tangled with the federal government in a highly publicized armed standoff in 2014, Bundy attracted dozens of occupiers who insisted the federal government had no right to own the wildlife refuge land.

In Medenbach, Bundy found an ardent supporter. And in Bundy and his allies—many of them men in camouflage, in trucks, armed with guns and thousands of rounds of ammunition—Medenbach once and for all found his people.

“This was fitting in with exactly what I was looking for,” Medenbach said last September, months after his arrest. He considers the occupation a form of divine intervention in his life: “the providence of the Lord stepping in.” One might say that when he was arrested in Burns, he was exactly where he wanted to be.

The way Ken Medenbach tells his story, his confrontation with the government began in 1988, when he purchased five acres of land in Central Oregon for $700. “I had a dream to live someplace up in the hills. Freedom,” he explains. “Living up here in the high desert, I feel like I’m on top of the world.” The Massachusetts native had lived in the Eugene area since he was a teenager. As an adult, he ran into frequent legal troubles, including charges for driving drunk and without a license.

He also found God, he says, and wanted to get away from it all.

The next year, he built a small, makeshift cabin on his five-acre property and moved in. “I was just minding my own business,” he says. “I came home one day and I found stop-work orders on all of my buildings. I called the county and said, ‘What’s with all these stop-work orders? It’s my land, it’s paid for. I paid my taxes, leave me alone,’” he recalls. “They said, ‘No, no, that’s not how it works, Mr. Medenbach.’” He was told he needed permits for everything: conditional use, plumbing, to have an outhouse.

“I said, Hey, look, this is my land, I’m going to do what I want with it, I’m not hurting nobody—sue me,’” he says. “So that’s what they did.”

In the ’90s, Medenbach engaged in several acts of protest. He would find a swatch of public land, put a small, shanty-like cabin on it, and then send a letter to officials saying that the federal government can’t own land. According to a May 1995 story in the Eugene Register-Guard (“Squatter Arrested on Old Warrant”), Medenbach set up a cabin on land adjacent to his property, then told the Prineville office of the Bureau of Land Management “to cease and desist” from managing the 640 acres there.

The then-42-year-old Medenbach told reporters, “I feel the Lord’s telling me to possess the land ... because the US Constitution says the government does not own land.” Just a few days later, Medenbach added: “If they want the land, they can take my life. Our forefathers died for these rights 200 years ago. I’ll die for them now.”

In newspaper articles, Medenbach often comes across as an outlier, a “would-be homesteader” hewing to his own interpretation of property rights. In fact, federal land management in western states became a national issue in the 1970s and ’80s during the so-called Sagebrush Rebellion: a widespread movement to put states and local governments in control of public lands, particularly for ranching, agriculture, and industries like logging or mining.

For generations the West had been run by ranchers—some of the first white people to settle the western United States, particularly in the Great Basin, a swath of land extending from Utah across Nevada and touching what is now Harney County. Ranchers “feel they have historically been priority users,” says Leisl Carr Childers, whose essay “The Angry West: Understanding the Sagebrush Rebellion in Rural Nevada” appeared in the 2015 book Bridging the Distance: Common Issues of the Rural West. “They controlled the Great Basin.” But in the late 1960s, ranchers and farmers started to feel their hold slipping, as land-use decisions began to involve outdoor recreationists and wildlife preservationists. A 1979 Newsweek cover headline captured their anger: “Get off our backs, Uncle Sam.”

Separately, across the country ad hoc “militia” groups were springing up—a loosely bound movement fueled by nonmainstream interpretations of the Constitution, Christianity, and the proper role of the federal government. The militias would find rallying points—Idaho’s 1992 Ruby Ridge standoff, in which three people died, or the 1993 raid on the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, where scores were killed.

For two decades in Oregon—starting back when Ammon Bundy was just a teenager—Medenbach’s actions suggested that angst over federal land ownership could one day merge with militia-style activism. Medenbach himself says that after Ruby Ridge and Waco, he became frightened. “Here I am fighting the government just to have a place to live,” he recalls. “How long until they send out snipers to pick me off?”

In 1995, during the dispute over his construction on BLM land, Medenbach spent a month in Lane County jail and was booted off the property. He then attempted to sue two Oregon judges. “They’re all corrupt, at the federal level, the state level, and the county level,” he told reporters after his complaints were mailed back to him.

Medenbach recalls that around then, he began to receive attention from elsewhere. A Washington state–based militia group contacted him, he says, to talk about taking over part of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. “I said, ‘I’ll tell you what, I’m not doing anything, I’ll come up and do it.’ I went up there, popped up my tent,” he recalls, adding that he set out a harmless inert grenade and an empty fertilizer bag to appear more menacing, and so no one would disturb his campsite. “I sent the Forest Service a notice saying, ‘I’m taking all of the federal lands in Skamania County for the people of Skamania County.’”

Again, he was arrested. In a 1997 Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals decision, the court wrote Medenbach “poses a risk to the safety of other persons or the community because [he] acknowledges intimidation practices, references ‘Ruby Ridge’ and ‘Waco, Texas,’ and clearly would not follow conditions of release restraining his presence at the scene of the alleged unlawful activity.”

“I went home and said, ‘I’m done with this stuff,’” Medenbach recalls. “There’s nobody here supporting me, and nobody’s gonna until they lose their jobs, lose their home, can’t feed their children.”

Years passed. He scraped together a living by building cabins and picking up odd jobs. He sold chainsaw-formed wood creations—intricately cut grizzly bears and bald eagles—at high-end Sunriver art galleries and rural roadside stands. In his spare time, he studied the Constitution and read Supreme Court decisions.

In the spring of 2014, he read about the Bundy family’s standoff with the BLM on their Bunkerville, Nevada, ranch—the culmination of 20 years of illegally allowing cattle to graze on federal land. The next year, he drove to Bunkerville and met the Bundys. He soon resumed his own battles: in spring 2015, he joined a dispute about mining rights at Sugar Pine in Southern Oregon, set up a cabin on federal land, and told BLM officers he wasn’t leaving.

On January 2, 2016, Medenbach joined a crowd in the parking lot of the town’s Safeway. It was another cold, sunny afternoon in Burns, two weeks before his arrest at the same place. The people gathered had driven from all around—Nevada, California, Idaho—to protest the imprisonment of two local ranchers on arson convictions. For hours that day, Medenbach marched in their ranks, gloved hands waving American flags against a blue winter sky.

When the marchers arrived back at Safeway, Ammon Bundy—a 40-year-old in a brown cowboy hat—stood up on a snowbank. “I’m asking you to follow me and go to the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, and we’re gonna make a hard stand,” Bundy called out.

“What’s the issue?” one man shouted.

Bundy was vague: “We’re going to insist that the Constitution be protected here in this county!”

Medenbach stood just a few feet away from Bundy, and piped up in support. “These are not federal lands! These are state lands!” Medenbach yelled. “They don’t belong to the federal government!”

“That’s right!” Bundy called back.

The sudden seizure of a remote tract of federal land drew rapt attention—and, from many, anger. On Twitter, the group was branded with a pair of derisive hashtags—#yallqaeda and #vanillaisis. For 41 days, militiamen, ranchers, veterans, gospel singers, and even children treated the refuge as their own. Occupiers ripped out a fence, used heavy equipment to dig trenches, lit campfires, sang songs, held prayer circles, and fired guns. They renamed the refuge, too, and replaced its signs with a name they felt more fitting of their mission: the Harney County Resource Center.

Bundy, at daily press conferences, said they were prepared to stay until the refuge lands were returned to the people of Harney County, and controlled by the state of Oregon. The Constitution, Bundy said, was their guide, and when the government realized it couldn’t legally own land, the refuge would just be handed back to the people, with the aim of “getting the ranchers back to ranching, the miners back to mining, putting the loggers back to logging.”

Bundy and others, including Medenbach, frequently cite Article 1, Section 8, Clause 17 of the Constitution, which they interpret as sharply limiting the federal government’s ability to own real estate. Legal experts scratch their heads. “The law is very clear,” says Michael Blumm, a professor at Lewis & Clark Law School in Portland and a scholar on environmental and public lands laws. “What they were claiming the law was is not true.”

“There is absolutely no basis,” says Margie Paris, a University of Oregon law professor who specializes in criminal law. “They’re pulling these notions out of thin air.” Carr Childers, the Sagebrush Rebellion historian, says that although in some ways the Malheur occupation felt like a reemergence of the ’70s movement, it also marked a distinct shift in rhetoric and tactics: “Never once during the earlier Sagebrush Rebellion did anyone take over a piece of federal real estate,” she says.

Medenbach’s mid-occupation capture made him the first of more than two dozen people arrested during the Malheur drama. (One occupier was killed during an arrest.) He was charged with conspiracy to impede federal officers, and for stealing that white pickup—property of the refuge. He also faced charges stemming from the heated 2015 confrontation at the Sugar Pine mine.

Medenbach was scheduled to stand trial in a Portland courtroom alongside Bundy and five other Malheur occupiers in September. (Seven more will go on trial here this month, with jury selection scheduled to start on Valentine’s Day.) For months, free on bail, he appeared at court hearings. One warm fall day, during jury screening, Medenbach unzipped his coat to reveal a black dress shirt emblazoned with white letters reading, in part, “The jury has the right to judge the law as well as the fact in controversy”—a nod to jury nullification, the idea that jurors can render decisions in accord with their hearts, not just the law. Judge Anna Brown noticed, and told him not to wear it again.

In October, Medenbach—who represented himself in a hybrid defense team with a court-appointed defender, Lake Oswego attorney Matthew Schindler—protested when Brown would not allow him to ask certain questions of a witness. “The corruption continues!” he yelled. Brown shot him a stern look.

Medenbach, like several other defendants, testified. Schindler told the jury Medenbach’s tale of skirmishes with the government. He told them about the cabins, the tent, the arrests—all of it. Medenbach called the Bundy family his “heroes” and said he did not fear prison time.

“I’ve been waiting for 21 years to get where I am right now,” he said as he sat on the witness stand.

Midtrial, Medenbach requested a leave of absence from the courtroom, which the judge granted. His attorney said he needed medical attention: “old guy problems,” Schindler called it.

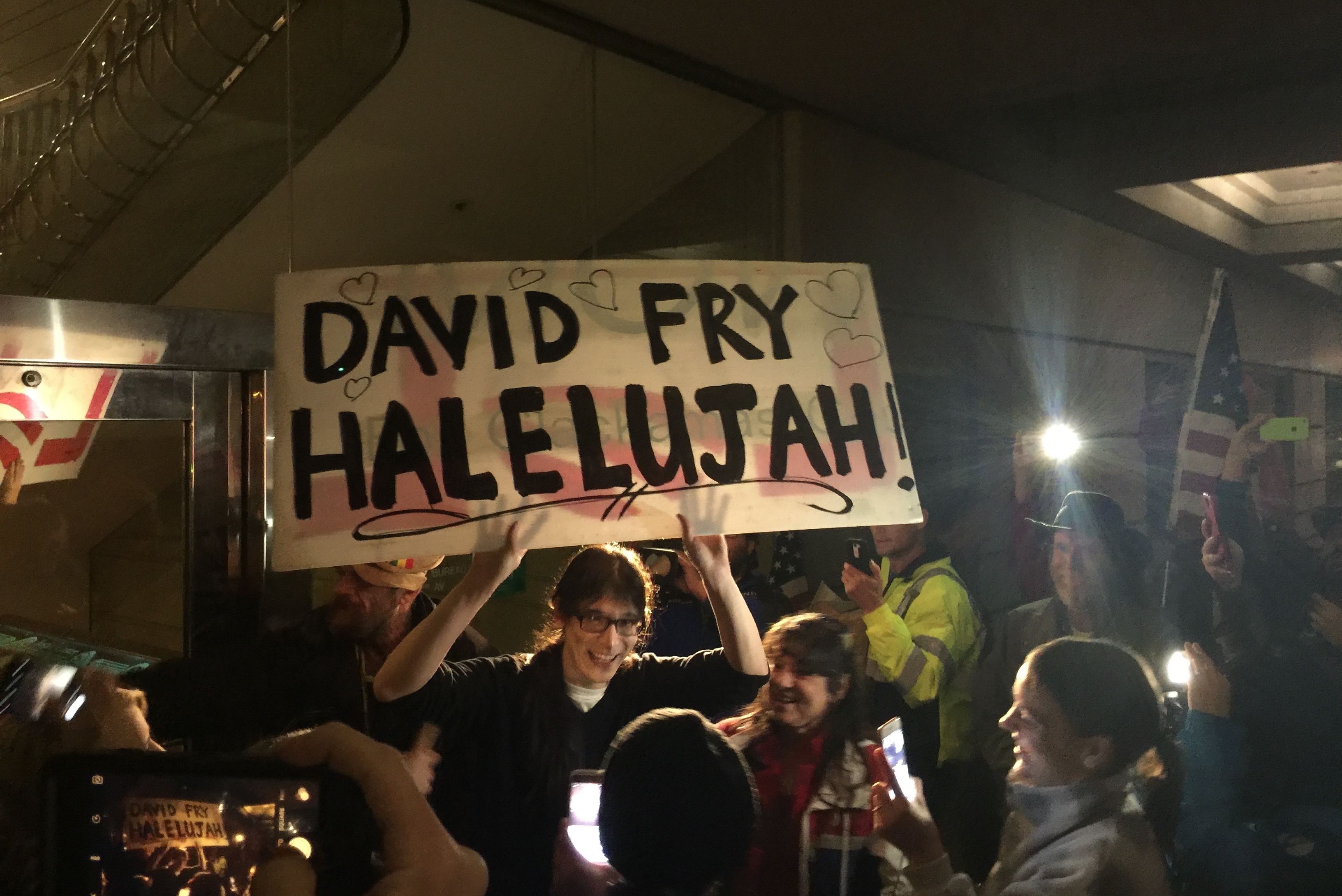

On October 27, the verdict came. Not guilty—acquittal on all charges, for all defendants. The decision was a shock to anyone who observed the trial. Even the defense attorneys seemed stunned—especially that Medenbach was found not guilty of stealing the truck, a vehicle 30 miles from where it belonged when he was arrested.

The verdict reverberated, cutting through the dense pre-election news cycle. Analysts speculated that, perhaps, prosecutors fumbled when they chose conspiracy charges; that they got greedy pursuing heavy prison time instead of more straightforward offenses. One juror told the Oregonian the prosecutors didn’t prove any conspiracy. Other observers have said the jury simply did what Medenbach pushed for, and judged with their hearts.

At the critical moment, Medenbach was lying in bed, recovering from a blood infection. His phone rang—it was a Salem Statesman-Journal reporter: “He says, ‘You all got acquitted.’” He soon talked to Schindler, their phone conversation almost drowned out by the chaotic scene of cheering supporters at the courthouse and Medenbach’s own emotions. Tears rolled down his face.

“He can’t stop weeping,” Schindler told reporters.

Weeks later, long after the verdict had been eclipsed by the November election results, Medenbach was still recovering at home in La Pine. As the anniversary of the occupation approached, he described himself as more energized than ever, determined to make government officials know that he won’t stop fighting to radically transform how the lands of the West are run.

“If I’m getting led by the Holy Spirit,” he said, “there’s nothing that can stop me.”

Top Image: Courtesy Flickr/Ken Lund