The Militia Verdict: 'Not Guilty' Was Just Another Chapter in an Ongoing Oregon Saga

On Thursday afternoon, October 27, when seven occupiers of the Malheur National Wildlife refuge were acquitted of all charges, they found themselves—again—in the national spotlight. It was a scene pulled from a movie script—a red, white, and blue blur of joy and confusion. One older defendant was swarmed by reporters, pressing him flat against the glass doors of the federal courthouse, cameras and microphones inches from his bearded face.

On the sidewalk, the defendants’ attorneys were assaulted with questions—one, in particular, repeated again and again: “Did you expect this verdict?”

Supporters waved flags and yelled passages from the Constitution as they paced the sidewalk. Others marched a horse in traffic. Its rider, at one point, stopped to make a show of turning his American flag—which he had been flying for weeks upside down—right side up once and for all. Cameras clicked and flashed all around him.

Some people might call what happened last week history; others might say it was tragedy. But however you look at it, a page in Oregon’s saga was written on October 27—an important part of a long chapter that started much earlier.

It was a frigid day in a Burns, Oregon. January 2: just a day after 2015 became 2016. A group of people gathered in a Safeway parking lot. After a peaceful protest over the imprisonment of two local ranchers convicted of arson on federal land, a cowboy-hatted Idaho car fleet manager named Ammon Bundy jumped on top of a snowbank and told the crowd it was time to take more serious action. It was time, he said, to make a “hard stand”—to seize the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, a federally owned bird sanctuary 30 miles from town, and to unite behind a message of outrage and desperation on behalf of rural America—and a theory of the Constitution which holds that the federal government can’t own land (or do many other things it does).

For 41 days, Bundy and his followers made their hard stand. After taking over the refuge, they held press conferences saying they planned to stay for as long as it took for the land to be given back to the people of Harney County and the imprisoned ranchers freed. They held workshops on the Constitution. They received mail and held meetings. They prayed, lit campfires, fired guns, drove ATVs, rode horses, and pawed through file cabinets and boxes of ancient artifacts.

On January 26, Bundy and several others were arrested and brought to jail in Portland. That same day, one of the occupation’s leaders, Robert “LaVoy” Finicum, was shot and killed during a police stop. By February, the occupation was completely dismantled. Bundy, his brother and 24 others were named on a federal indictment charging them with conspiracy to impede federal officers from performing their official duties.

I was there as they all appeared in federal court, covering the story for the Washington Post, and saw these men, overnight, reduced from gun-toting cowboys to simple men in shackles and jail scrubs.

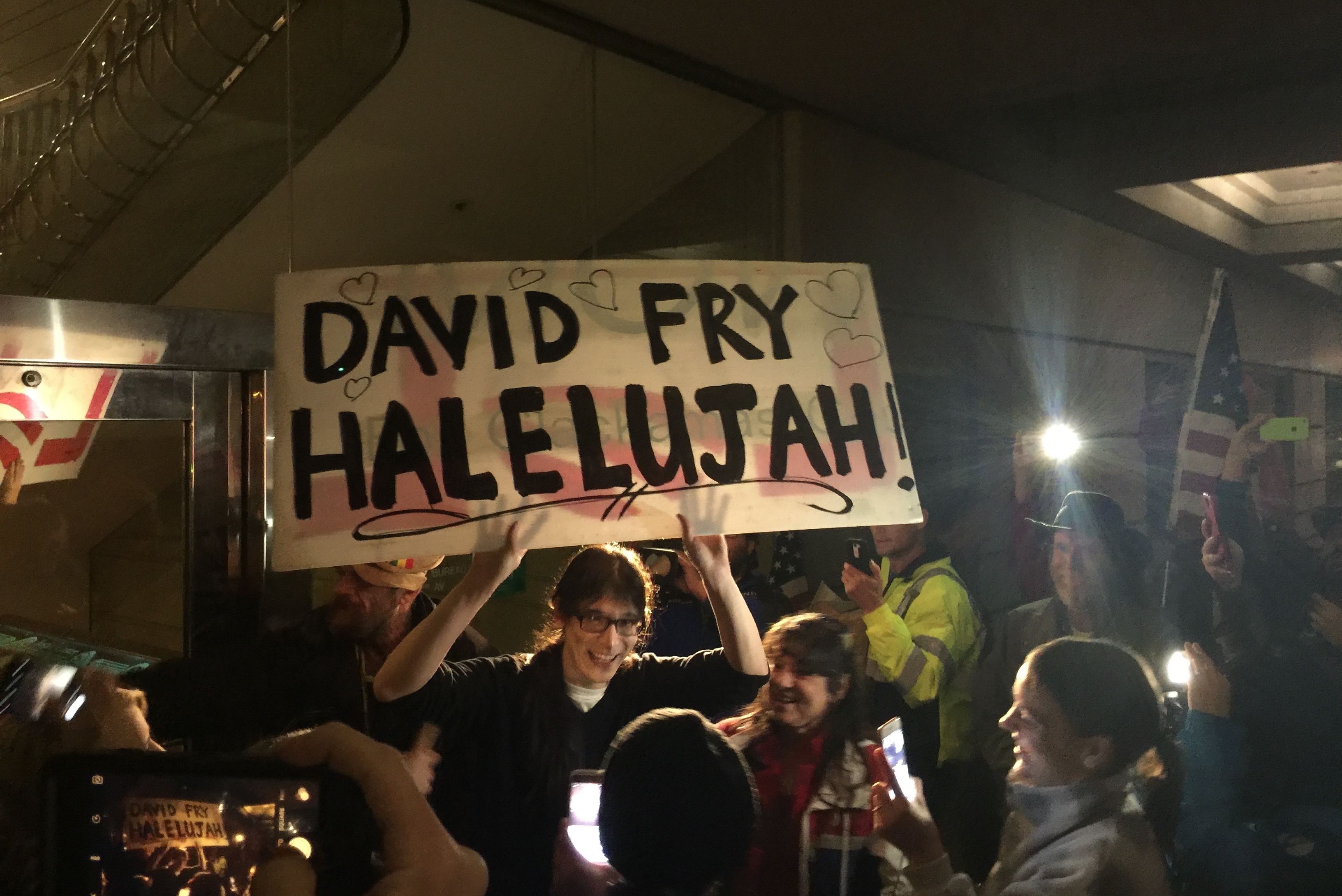

Top: David Fry, with co-defendant Jeff Banta, talks to supporters after his release from jail. Bottom (from right): Defendant Neil Wampler speaks to reporters after his acquittal; Patriot supporters march through downtown Portland shouting "not guilty!" after the acquittal was announced; Shawna Cox talks to reporters outside the courthouse after being acquitted of all charges.

Image: Leah Sottile

Most pleaded guilty as 2016 ticked by. But on September 13, a trial for the Bundys and five others began. The prosecution’s job seemed easy, given that Bundy and his men had produced a constant stream of videos at the refuge, giving interviews about tyrannical government overreach as they held guns on their hips. They took photos of themselves tearing down signs, live-streaming as they cut fences and posting to social media telling others to join them.

On September 19, Linda Beck, a refuge fish biologist whose office was used as HQ by Bundy, raised her eyebrows at a question as to why she didn’t go to work during the occupation: “Because there were people with guns in my office,” she testified. Prosecutors showed the jury 22 long guns, 12 handguns, and 16,000 rounds of live ammunition found at the refuge.

But when seven defense attorneys presented their case, the jury was given a different story to consider: The occupation was a protest. The guns simply served to get people to pay attention. The shooting of Finicum proved government overreach. There were never any threats against employees.

For 10 hours over the course of three days, Ammon Bundy testified about why he took over the refuge. He offered to read to the court the section of the Constitution that he believes says bars federal government from owning land. (His offer was denied.) He talked about his religion. He asserted that the government was out to get his family. (Bundy faces charges alongside four of his brothers and his father in Nevada for a 2014 standoff on the family ranch.) At times he became emotional on the subject of government power: “They’re too smart,” he sobbed. “They’re too strong.”

When it came time for the prosecutors to cross-examine him, they were shockingly brief: 15 minutes of rapid-fire questions. On a break, I asked a fellow reporter why she thought the prosecutor didn’t spend more time picking apart Bundy’s hours of testimony. She shrugged.

By Thursday, October 27, the verdict was in: not guilty, across the board. For hours after the verdict, I talked to everyone I could. Defendants were shocked. Defense attorneys told me they were “astonished,” “stunned” at the win they fought so hard for. Supporters hugged and cried and waved flags. They marched a horse outside the courthouse and yelled, “Not guilty! Not guilty!”

Now we know that one juror, currently known only as No. 4, saw the prosecution’s approach as arrogant. “The air of triumphalism that the prosecution brought was not lost on any of us,” he wrote in an e-mail to the Oregonian, “nor was it warranted given their burden of proof.”

He said, simply, proof of conspiracy was never given. “We were not asked to judge on bullets and hurt feelings, rather to decide if any agreement was made with an illegal object in mind,” he wrote.

On the steps of the courthouse afterward, the defendants shouted about their victory for the Constitution—that their interpretation was right all along. But that’s not what the jury decided on October 27. The verdict really proves only that the government is not as smart, or as strong, as Ammon Bundy says it is.

After the occupation, people in Burns saw generations-long friendships severed. After the trial, detractors posted the addresses of defense attorneys on Twitter and said they’d occupy their offices. My own work has caused people I’ve known almost my entire life to question why the media covered the occupation the way it did, to throw bitter insults at me for even reporting on it. I’ve received hate mail that shook me to my core. My husband, at one point, asked me not to tell him about it anymore.

In the end, though Ammon Bundy’s interpretation of the Constitution remains—to put it politely—far from mainstream, his protest worked. It got people to pay attention to rural America. But the occupation and the ensuing trial didn’t unite people; it just pushed them even further apart.

Top Photo: David Fry holds a sign on the steps of the Multnomah County Justice Center, upon his release from 9 months in jail. (Image: Leah Sottile)