Musician Laura Veirs Switches Gears for New Kids' Book on Elizabeth Cotten

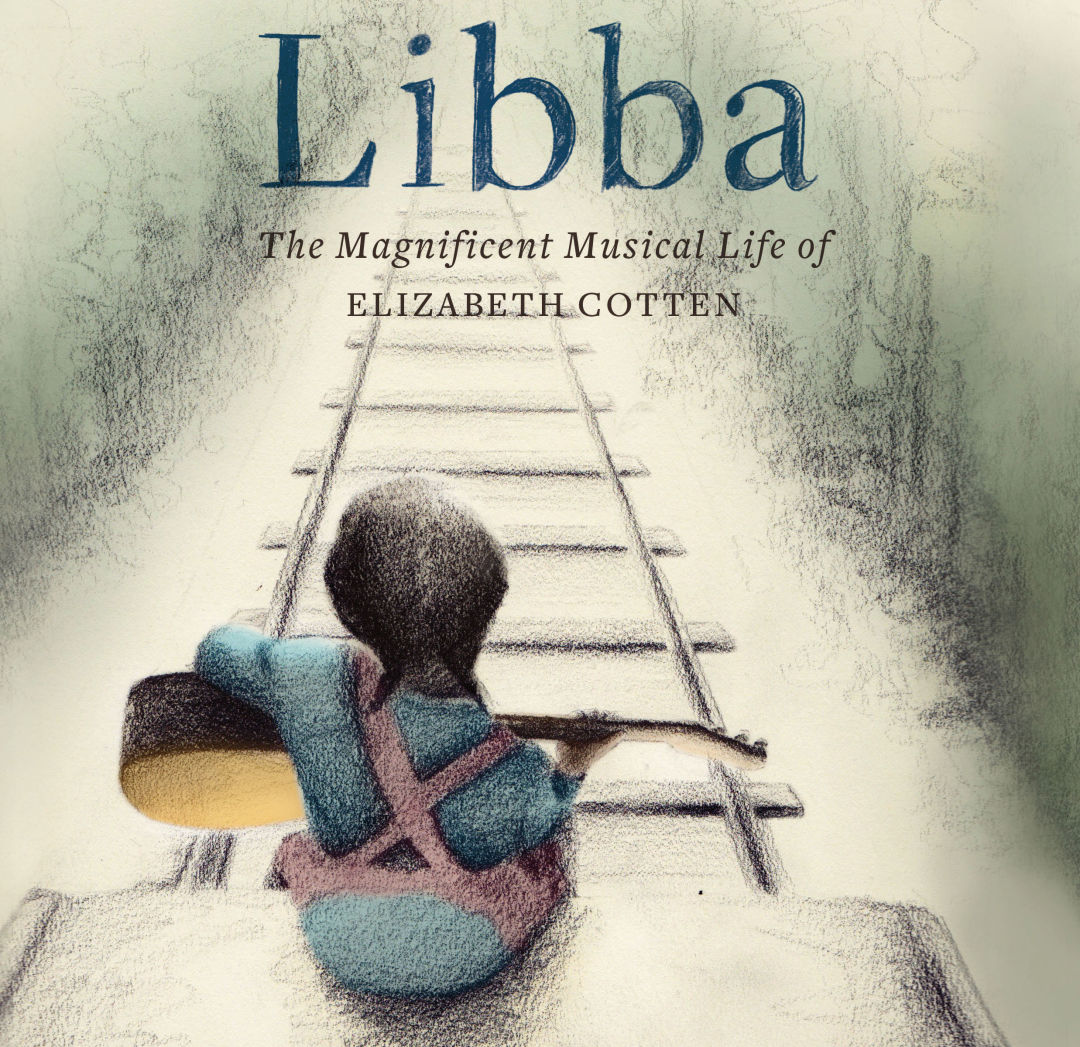

Image: Courtesy Chronicle Books

In 1985, Elizabeth “Libba” Cotten won a Grammy, but, as an African American folk singer born and raised in the segregated South in the early 1900s, her path to fame was anything but straightforward. A lefty, she taught herself to play on her brother’s guitar upside down and backwards, a style now known as “Cotten picking.” She composed her first original song and one of the best-loved folks songs today “Freight Trains,” when she was around 11 years old.

As a fellow musician, Portland singer-songwriter Laura Veirs fell in love with Cotten's songs, and then her story, which includes a four-decade break from music until she met composer Ruth Crawford Seeger and ethnomusicologist and father to Pete Seeger, Charles, who went on to spread the word about her music. So Veirs set out to write a children’s book on the subject. The result, Libba: The Magnificent Musical Life of Elizabeth Cotten, is a lyrically narrated and sweetly illustrated historical biography that reminds readers never to surrender their dreams. And it didn’t come without its complications, becoming a major learning experience for its author. “This book helped me realize how I’d been living in a white Portland bubble and how I wanted to get out of that,” says Veirs. “The book has changed my perspective that way in terms of connecting me with people. Art and music can do that.”

What made you decide to write a children’s book about Libba?

My parents sang her song “Freight Train” to me growing up, and I had played her songs onstage for years because she was a really amazing guitarist. She played really complicated finger-style guitar, which was one of the foundations of my guitar playing style, the country blues style. I just found it so interesting that someone could put their instrument away for so long and then just through coincidence and through an act of God, which is what Libba’s granddaughter told me, meet this musical family and find herself back in that world.

What moral do you hope children take from the book?

You can accomplish things at any age. You can be really young or you can be really old. You can defer a dream, or life might defer your dream for you, but you can realize it later. You can keep it hidden like a seed, and then it can come to fruit later, so it’s about maintaining your hope through challenging times and also doing things your own way. It’s okay if you don’t hold the guitar the right way. What’s the “right way” anyway? You can do things a different way and still be accomplished. A lot of times, children get corralled into sameness.

As a white woman writing about an African American, how did you ensure you were being culturally respectful?

I really didn’t think about race when I thought about the story initially. I just thought, “I like this story; I’m going to write it.” After I did my first round of interviews, I realized, “Wow, I haven’t talked to a black person. That’s not right. I need to speak to someone in her family.” I really struggled in that first round to find somebody who was alive and would speak to me. Eventually, [I found her granddaughter] Brenda Evans, who sang on “Shake Sugaree” when she was 12. I found out, through talking to Brenda, that they wrote “Shake Sugaree” together.

What changes did you make because of your interview with Brenda Evans?

I deemphasized the Seeger family. I wanted to be sensitive to not have the book be white saviorism, so we [commissioned] a sensitivity reader, who works at the Museum of African Diaspora in San Francisco. He found one place where we could add a new sentence about Libba having her own agency: “But it was Libba’s perseverance, her love of music, and her belief in herself that gave the world her voice.”

Did you ever question whether you were best person to tell this story?

I did a lot of reading around race, and I talked about it with Tatyana [Fazlalizadeh, the activist–artist who illustrated the book]. She didn’t have any question about whether I should be doing it, but I had a lot of questions through that process. “Am I the right person to be telling this? Am I getting this right?” I really wanted to be careful. There’s a lot of fear in some of the groups of people that I hang out with in the children book writing world and in the art world that people shouldn’t talk about people from a different culture, you should only write your own story, but I disagree with that. I think we can speak about other people’s stories, but we need to be really careful and thoughtful and do our due diligence and then it’s OK because, if you can’t write about other people’s cultures or stories, then all we’re left with, as a human race, is memoir.