A New Book Asks Questions about a Mother Turned Killer

Image: Pablo Amargo

Just after 1 a.m. on May 23, 2009, Amanda Stott-Smith drove to the middle of the Sellwood Bridge and dropped her two children into the Willamette River, more than 90 feet below. Forty minutes later, rescuers pulled 7-year-old Trinity and 4-year-old Eldon out of the water. Trinity lived, Eldon had died. Amanda was arrested and later sentenced to 35 years in prison.

Portland writer Nancy Rommelmann remembers picking up a newspaper featuring Stott-Smith’s mugshot within days of the event. “I was standing at the kitchen counter drinking a cup of coffee, looking at this picture of this woman, and I just thought, how does this happen? How does a mother drive to a bridge in the middle of the night and throw her two young children off? I instantly knew I had to find out what was going on.”

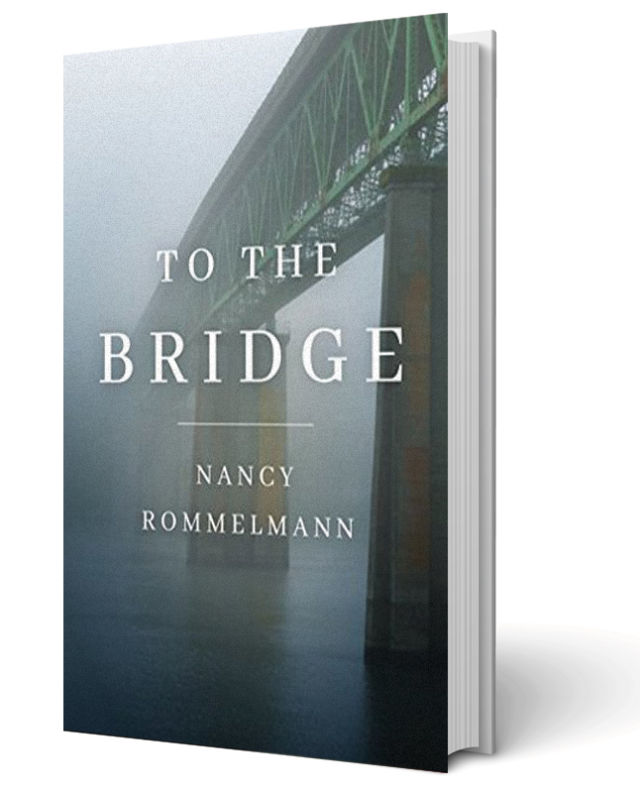

Thus began a nine-year fact-finding odyssey culminating in To the Bridge, published in July by Little A, Amazon’s literary fiction and nonfiction publishing imprint. The book is, as Rommelmann herself points out, less a whodunit than a whydunit: a drive to comprehend an event that is, to most of us, incomprehensible.

The search led Rommelmann from statistical deep dives—victims of filicide are 4 years old on average, readers learn, while the average age of a filicidal parent is 31—to several court appearances, prison records, letters from a convicted triple murderer, late-night anonymous phone calls, and one unlikely friendship.

She spoke to Stott-Smith’s school friends; friends of the children’s father, Jason; neighbors; Stott-Smith’s lawyer, Kenneth Hadley; and close family members. She attended Stott-Smith’s arraignment and trial, and combed through Eldon’s autopsy report, his mother’s prison records, her notebooks, medical reports, and police reports.

All, as she explains in To the Bridge, to bear witness to the loss of a child.

Many connected to the family were initially reluctant to talk to her. It was only a year after the crime, when Stott-Smith was sentenced, that people began to reach out to Rommelmann, who at the time was blogging about the incident. “As soon as her fate was set, they had to tell what they knew,” she says. “They all felt they had mitigating information. A lot of them knew these kids, and it was crushing them that none of this was going to be remembered, or told in a way that they felt that they could sleep at night.”

The voices most notably absent from the book are those of the story’s surviving protagonists: Trinity, Jason, and Amanda. Despite numerous attempts to talk to Stott-Smith, Rommelmann never got to interview her. When that lack of access made her wonder whether she could do justice to this story, Rommelmann’s sister-in-law offered clarity: “She said, you know, Nancy, a lot of people have written books about George Washington who never got to interview him.”

Stott-Smith’s family “closed ranks,” says Rommelmann. “They just could not, would not talk about it even among themselves,” she says. Except, that is, for one person. “Amanda’s grandmother needed to.”

What emerges from this chorus of voices and perspectives, among them Rommelmann’s own as both mother and writer, is a story of addiction, abuse, neglect, alcoholism, deceit, and systemic failure. It’s an emotionally honest, meticulous examination of a confluence of circumstances that culminated in a deadly act, and the complicity of our own city and culture in its aftermath.

Rommelmann began her research at a time of public outrage against Stott-Smith. Incensed Portlanders suggested hanging her from the bridge, or “tattooing ‘killer’ on her forehead and letting her out into the general population,” Rommelmann recalls. But Rommelmann’s book tells a complex, shifting story that also denies any pat explanation for the action at its center. Words like “crazy” or “incomprehensible” may be the easiest to access when faced with such a crime, but that doesn’t make them accurate.

“If we let mothers go around killing kids, then the world ends, right? So we can’t accept that she could ever do this with some sort of plan, or that she didn’t just snap,” says Rommelmann. “But I absolutely do not think anything comes out of the blue. This one certainly did not come out of the blue.”

Somewhere outside the pages of Rommelmann’s book, the real lives captured therein continue, lives that could be affected by the information she presents. “Have I considered that Trinity might see this book at some time? Sure. And that might be the only person that I feel very tenderly about,” says Rommelmann. Now that the book is on the cusp of release, however, she says her part is done. “It’s going to be out in the world. Some people are going to be glad it is. Some people are not going to be, but at this point it’s their book. I have no control over it at this point. I did the best job I could, and now it’s up to them. It’s up to the reader.”

Image: Courtesy Little A

Excerpt

In the following excerpt from Nancy Rommelmann’s To the Bridge, the accused appears at Portland’s Justice Center.

On Tuesday, May 26, Amanda Stott-Smith was arraigned at Justice Center in downtown Portland. Two cameramen were the only people in the gallery when I arrived. We wondered whether Amanda would appear facing forward or looking down. We talked about other parents who had murdered their children in Oregon: Christian Longo, who strangled his wife and baby, then threw his two other children off a bridge; Diane Downs, who shot her three children inside of her car.

[...]

Two guards led Amanda in. She wore a padded pine-green vest, the prison-issued “turtle shell” given to those on suicide watch. She looked Native American, maybe; her skin was a creamy coffee color, her cheekbones high and wide. Her thick dark hair was loose and not untidy. She was not, as the TV cameramen had guessed, looking at the floor. She kept her face up and stared straight ahead, but her eyes landed nowhere in the room.

The judge read the charges: one count of aggravated murder, one of attempted aggravated murder. The “aggravated” designation carried heavier penalties and, in this instance, indicated that the crimes were committed intentionally. If Amanda’s case went to trial, she would face the death penalty.

Amanda’s attorney mentioned he was here as a courtesy to the family. It was unclear what this meant. I could not stop staring at Amanda, whose gaze remained unfixed. She looked as though standing were an effort, as though a weight on her shoulders was dragging her forward and down. The judge asked, “Do you understand the nature of the charges against you?”

Amanda did not answer. The judge asked again, “Do you understand the charges against you?”

This time, Amanda looked toward the judge. She appeared to move her lips. Everyone in the courtroom was waiting to hear what she said.

What came out was, “Muh.”

At this, a syllable later interpreted in editorials, by police and politicians, as “No one will ever understand how this happened” and “No one could ever have seen this coming,” Judge Philbrook issued her orders: Amanda Stott-Smith would remain in custody until she reappeared on June 3.

A guard took Amanda’s elbow to escort her from the room. Amanda did not appear to understand the gesture. Another guard turned her, and she moved out the door as if moving through deep water.