Meet the Poets Who Defined a Portland Era—and Are Still at It

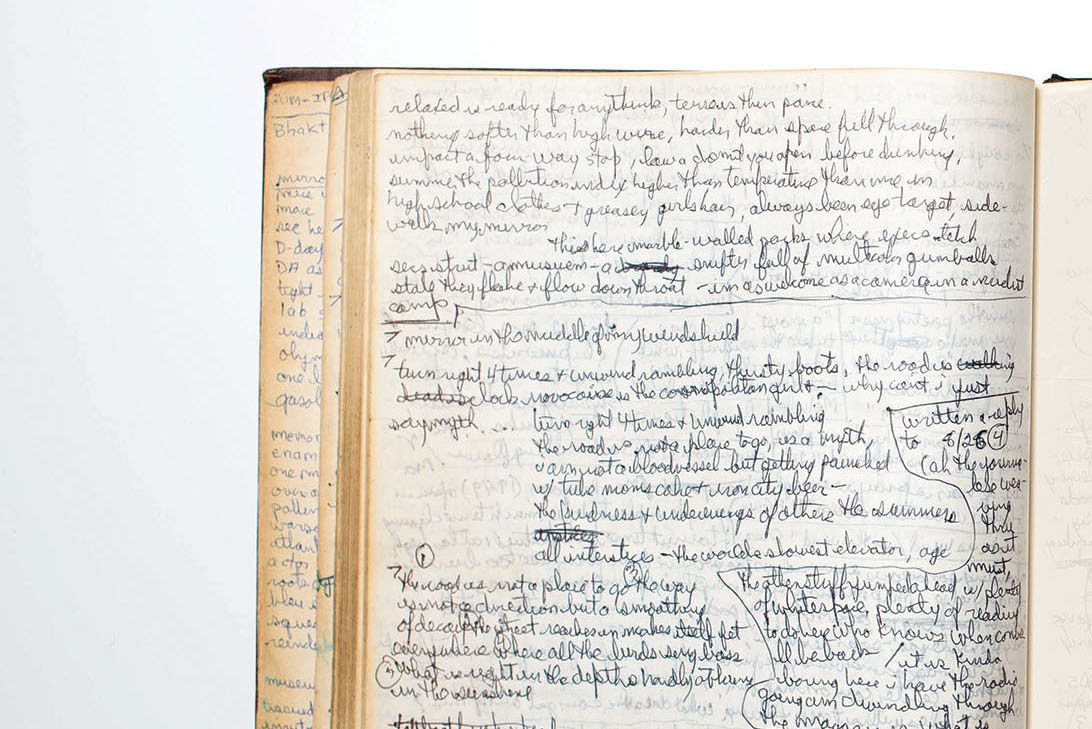

ABOVE: Image of a notebook Dan Raphael kept during graduate school in 1974 and 1975, just before the poet moved to Oregon (Photograph by Brian Breneman)

While many mourn the shuttered punk clubs and long-gone cheap rents of Old Portland, one major component of that creative bohemia is often overlooked: the poets, staging open mikes and poetry slams on music venues’ quiet nights, publishing their work in the Portland Poetry Anthology or the Clinton Street Quarterly, holding an annual festival, enjoying coverage in the Oregonian.

“These poets have been the voice of Portland in a way,” says Leanne Grabel, a poet who helped name Wordstock. (Cofounder Larry Colton gave her $50 for the idea, she remembers, for what’s now been dully renamed the Portland Book Festival.) Grabel hosted readings at Café Lena, a restaurant she ran with her husband during the ’90s. Satyricon, the legendary punk rock club in Old Town, had a poetry open mike night, as did the Long Goodbye in what’s now the Pearl District, where Geek Love author Katherine Dunn tended bar.

Unlike those rock clubs and cheap rents, a lot of the poets are still in town, finding ways to support themselves beyond the pittances paid for published work. Many are retired, with Social Security and even PERS. (Several were teachers or other public employees, or their spouses were.) For some, it means more time to volunteer at Street Roots, do readings at Broadway Books, cheer on a granddaughter’s roller derby team, or just work on their next collection. They’re still narrating our city, even if many of us have never heard them: “still writing, still reading, as a response to and revelation of our world,” says Grabel. She recently interviewed some of what she calls her “friends, peers, listeners, inspirations, partners in crime” (as well as herself) to learn what brought them here and what keeps them writing. —Margaret Seiler

Leanne Grabel

68, born in Stockton, California, went to Stanford on a math scholarship; taught at Portland Public Schools, the Rosemont Treatment Center, and elsewhere; ran Café Lena for a decade; works include Gold Shoes and Brontosaurus: Memoir of a Sex Life

I moved to Portland because of poetry, to be a poet, to be a member of the Portland poetry community, such as it was, is, and will probably forever be—vibrant, a little ragtag, sad, slow, sometimes brilliant, always cracked open like a raw egg. It was 44 years ago, August.

The open mike was at the Earth Tavern, near Cinema21. The host was a 34-year-old Walt Curtis. He swooped and swooned and swiveled to his words. I was utterly mesmerized and joyous. The next day I was utterly mesmerized by the stylized waterfalls of Keller Fountain, the blue of the sky, and the majesty of Mount Hood. (Mountainous Blazer Rodney Hood wasn’t born yet, although now I like him, too.)

Two weeks later, after selling things down in Stockton, California—stereo, piano, albums, futon, etc.—I moved to Portland. My next poetry open mike was at the Long Goodbye on NW 10th and Everett, which became Jimmy Mak’s and is now Life of Riley. I trembled up to the mike one Tuesday night, literally pushed onstage by my friend, and read three poems. Heaven. I adored it: standing in front of a mike, pouring out my guts in words I’d sculpted to song, swooping, swooning, swiveling.

I wanted big fame and glory. I still do. I’m a Leo! I wanted to be Aretha Franklin or Patti Smith or Annie Lennox. I know poetry is detached from money, but I wanted to make money from my poetry. Of course I set myself up for disappointment. It’s what I do. In 45 years, the Portland poetry scene has had its ups and downs, and so have its poets. I still get asked to do readings. Last year was better than this year, but pieces are getting published. And I still love performing the best.

What are you working on now? I have been doing some readings lately with Russ Miller on guitar and Steve Sander doing backup vocals/noises/sounds. I’ve been using my old funky Casio for beats.

FROM TOP: Walt Curtis; Leanne Grabel at Café Lena (with friend and future furniture artist Todd Isaacs); Judith Barrington in the ’80s at a book party for her first collection, Trying to Be an Honest Woman

Image: Courtesy Leanne Grabel and Courtesy Judith Barrington

Judith Barrington

75, born in Brighton, England, during a World War II air raid; came to Portland for the summer in 1976 and never left; has been a journal editor, visiting poet, writing teacher, and housecleaner; cofounded Soapstone, a nonprofit to support women writers with residencies and retreats; works include The Conversation and Livesaving: A Memoir

I’m a poet because I don’t know much about anything else. I read a lot of poems as a kid. I was fortunate to go to a moderately good school in England—all girls, private. Writing poetry started as a secret occupation, with poems and notebooks hidden away in drawers. It was intricately connected to the shame I felt and secrecy because of being a lesbian without really understanding it.

The feminist book and print world was flourishing in the ’60s and ’70s. Women’s bookstores made it possible to actually tour and give readings, which taught me a whole lot about the sound of my poems. I went to the second Women in Print conference in Montreal. The huge array of small presses and writers was wonderful. It was the context in which I grew as a poet.

Most recently, my poetry life has been disappointing. I have had medical problems that sap my energy and I’ve found that writing about illness and old age doesn’t seem to sit well with editors.

What inspires you? Horses. Old women hitting fascists with handbags.

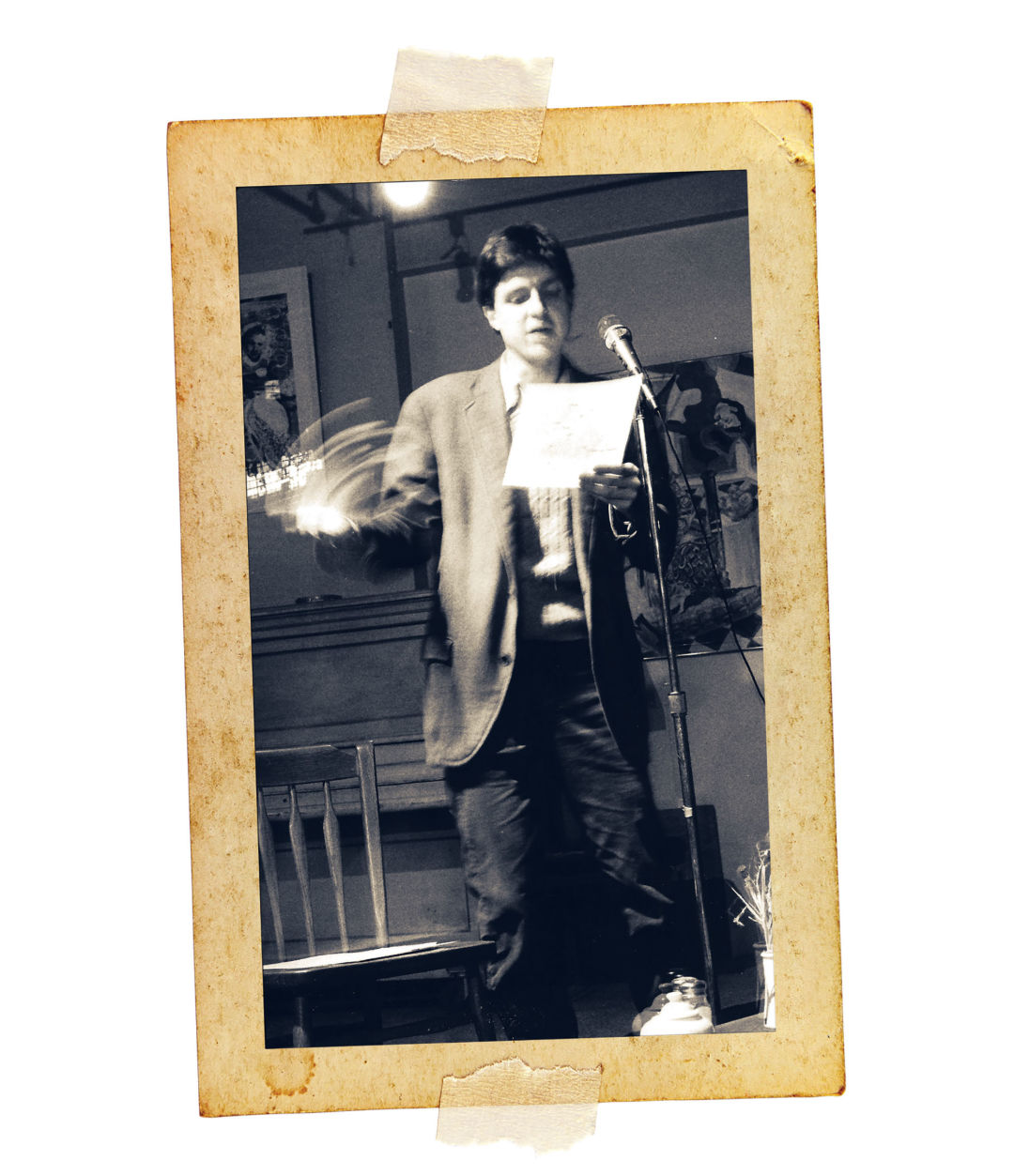

Casey Bush

66, born and raised in Michigan, has worked as a janitor, medical transcriptionist, technical writer, research administrator; works include JanesBonnets and the biographies Grandmaster from Oregon: The Life and Games of Arthur Dake and Inside the Black Box, about Oregon’s first neurologist, Robert Stone Dow

In 10th grade I wrote a book, The Confessions of the Hooded Rat. In verse. My parents never read poetry. Once I started, I never stopped. It’s a nasty habit. It’s decoding the world, but through language.

In 1973, I took second place in the Atlantic’s college poetry contest and first place in the Albion College poetry contest. I went to a dinner with the judge, Mark Strand. He was a major bore. Around the time I moved here—prompted by friends in a bluegrass band known variously as Virgin Territory and the Country Clap, closely associated with the legendary (and notorious) Holy Modal Rounders—I had two poems in the Oregonian. But the poetry editor rewrote one of them.

I write for myself. When I think it’s ready to share, I read it or publish it. I expected persecution. Free speech comes with a price. There was a period when my mail looked like it had been opened. In Michigan I was the propaganda minister for an anarchist campaign.

In the ’80s I used to lunch with Katherine Dunn (who wrote about boxing), and she encouraged me to write about my hobbies. “Chess players,” she said. “It would be a good place to sharpen your pencil.” So I did. And I won a bunch of chess awards and had a chess column in the Oregonian. But I always go back to poetry, though no one is really interested in poetry. You have to do other things.

I am not disillusioned. For me, the community of poets and writers in Portland has provided a peer group to which I have aspired and found a place. This is satisfying.

What are you working on now? A book of prose poems created as reactions to avant-garde jazz CDs for music website Audiophile Audition. And a collection of short stories exploring the all too common human trait that leads us to go along to get along.

ABOVE: Casey Bush reading at the Riverway Inn at SW 10th and Salmon (now the downtown Bike Gallery), circa 1988

Image: Courtesy Casey Bush

Tim Barnes

73, born and raised around Palo Alto, came to Oregon in 1973 to visit the woman who became his first wife, taught at Portland Community College for 25 years; works include poetry collection Definitions for a Lost Language and the nonfiction Wood Works: The Life and Writing of Charles Erskine Scott Wood; edits Friends of William

Stafford: A Journal & Newsletter for Poets & Poetry

It all began with my mother and her stories of the golden days in Hollywood, her time on Star Hill Farm in the Santa Cruz Mountains above Half Moon Bay. I was raised around artists, and I liked their company and energy. They seemed, among the many glum adults I encountered as a child, to be the happiest and most engaged with living well. And poets were left to be themselves. I became a poet to have elbow room in an emotional way.

And yet poets value relationships. They value falling in love. They value truth in the form of aesthetics, things that don’t have money attached. I started writing poetry when I was a teenager, and it had to do with girls. I wrote to deal with the feelings around the things that women and adolescence conjure. Then I found William Stafford. I fell in love with him. I saw Stafford read a few times. After he read, I just stood around amazed, wanting to hear anything else he might have to say.

The first job I had in Portland was at a Parry Center group home for teenage boys. I quit after two months; as a pacifist I had served two years alternative service in the Bay Area during the Vietnam War, and my pacificism was being challenged too often around these boys. That was the winter I became a poet. I’ve been a warehouseman, bookstore clerk, events manager, coach, basketball referee, librarian, and to get through when I was adjunct and doing PITS (Poetry in the Schools) I worked temp jobs, sometimes rather gritty work. I had a column in the early ’80s in Willamette Week called “Word Events.”

Early on I imagined myself going to writing conferences and hanging out with other poets, but that is not what happened. I got into teaching and that turned out to be a mixed experience, mostly good. Teaching is, however, filled with disappointment at the lack of serious interest or thoughtfulness in some of the students.

Has it turned out as I had hoped? I don’t know. Has it turned out? Yes, absolutely. I have waves of great contentment realizing I have Social Security, PERS, a financial security my romanticism wasn’t looking for. I ended up with a damn good life. All these books around me. I can write when I want. I have interesting friends. A nice house. Personal freedom. You know, all of us are poets in some way, especially in childhood. It’s a romantic notion but I’m holding to it.

What are you working on now? A manuscript of poems using Western American themes, harvesting poems from my journals (10 years behind)

Barbara LaMorticella

77, born in Cincinnati and raised around New York and Chicago; has been a community center director, medical transcriber, and radio host; works include 1997’s Rain on Waterless Mountain, a finalist for the Oregon Book Award

I came from a family that said about art: “Do you really like this shit?” I left home early and married young. My husband, Robert, and I moved to San Francisco in 1963 and were founding members of the Diggers (a direct-action political activist group) and the San Francisco Mime Troupe. Those were tumultuous times; when we left the city we moved to the woods in Point Reyes, and then left for parts unknown when things got very hot (phone calls from the FBI, a sheriff neighbor terrified of a hippie invasion). We loaded everything we owned in a truck and headed north. In those days people did that.

A sheriff pulled us over on Highway 30 near Forest Park. Our truck was so loaded we were an inch off the ground. We pulled up the nearest uphill road, which was Logie Trail. We pulled into a forest road to camp and promptly got stuck in the mud. I was pregnant with our second child. Robert and our friend hiked uphill a couple miles to the nearest house. Two old drunks were roasting a chicken on the porch. They told us about an abandoned house the owners would probably let us camp in. At 9 p.m. we knocked on the door of the house’s owner, Joe Satchell, who had a book called The New Radicals on his coffee table. I had worked on the book, and was thanked for my work in the introduction. Joe let us stay five years in the abandoned house, which we fixed up. This was in 1968. We bought a piece of property across the road, where I still live.

I wrote because I needed to express myself. Poetry seemed like an art you could practice in isolation and with little money. I never expected to make money or achieve literary glory. In the beginning I wrote under a pseudonym, Rain, because I was against the star system.

I read at open mikes but didn’t send stuff out. I’m trying to do that now in an organized way. Whatever recognition has come my way has been unexpected. The support and friendships poetry has brought have enriched my life immeasurably.

What inspires you? Observation of people and the natural world, words, phrases, movements of the heart, sometimes anger or tears.

Dan Raphael

68, born in Pittsburgh; recently retired from the DMV; has organized countless readings and reading series, including one called Poetland (80 poets reading in eight places over eight hours—and he’s organized a group reading with the poets from this story at 6:30 p.m. Monday, December 2, at Ford Food + Drink); collections include Impulse & Warp and Showing Light a Good Time

The only books around my house were mine or my sister’s. Our mom quit school after sixth grade to go to work, and our dad got thrown out of high school his junior year for beating up the vice principal. My parents weren’t educated. Urban ghetto setting. I just started writing a poem junior year of high school. I don’t understand why I would have written a poem. But I was impressed that I did without any logical reason why.

I came at poetry through performance. When I was 12, I was stuttering but didn’t if I was reading or had something memorized. It was easier to perform than to talk. I started going to a coffeehouse in downtown Pittsburgh where they were reading Ferlinghetti and Ginsberg.

A friend in grad school (I got my MFA in Bowling Green, Ohio) was from Oregon and said I should go there. I visited in summer 1975 and moved to Ashland in spring 1976. It was a coin flip between that and going to Washington, DC, where some of my friends were living. Ashland is a great place to live, but there’s no work and no money. I was a janitor at the Shakespeare Festival. I liked Oregon, and I liked cities; therefore, there was only one option. I got to Portland Labor Day of ’77.

I am still hopeful to get some broader recognition, maybe win a grant. I probably hold the record for the most applications to Literary Arts (and its predecessor, the Metropolitan Arts Council) without winning or being a finalist. (I’m just a big dog and I want to be petted on the head. Good poet. Good poet.) But peer recognition is most dear and sustaining, and I get a share of that. The most rewarding part is the poems themselves. I get so much pleasure and satisfaction from what I write.

What inspires you? Energy is building and I need some kind of crack for the words to come out. Sometimes I’ll think of a phrase. After movies. After concerts. Poem every week for KBOO evening news.

Doug Spangle

68, born in Roanoke, Virginia; grew up at national parks (dad was a park ranger who got into park and museum planning) with a stint in Jordan and then under evacuation in Greece due to the Six-Day War; went to college in Germany; worked as a maritime traffic operator

To compose or read a piece of poetry is to see the world with a sense of order. I was writing in my grandma’s house in the Laguna Mountains in Southern California. We’d sit in front of the fireplace and tell stories. In school, I liked folk songs and I was always making up stories and songs. And then Bob Dylan.

I remember going through Portland in ’63 on a family trip and thinking it was nice. I moved back stateside in 1975, striving in vain to adapt to my girlfriend’s home state of Iowa. Failing miserably at that, I fled with my window van to the Great Northwoods of northern Wisconsin. In 1978, I threw all my portables into a backpack and hitched on the Trans-Canada Highway. I was seriously tired of the Midwest and wanted to be back out on the Left Coast, and Portland seemed the most likely place for me. Besides, I wanted to pursue writing and knew of two wonderful writers, William Stafford and Ursula Le Guin, who seemed to be thriving here. I’d been reading Le Guin’s science fiction and poetry since I was in high school. When I first got here, in 1978, I stayed in the worst flophouse in Old Town—the West Hotel. I was looking for readings. Two days later I started going to the Long Goodbye. I soon fell into cahoots with the bad crowd at that tavern. This constituted the best of the local literati outside academia. Since then, I’ve emceed a bazillion open mikes, and I still attend such dives whenever I can.

I had been aware from a very early stage that writing would be unlikely to support me, and having no particular skills otherwise, I’ve always worked at semi-menial “writers’ jobs” such as hotel night clerk, dishwasher, busperson, Ma & Pa store clerk, carpenter’s flunky, and ultimately, for over 25 years, a maritime traffic coordinator. Since then, I’ve been a reading coach for SMART and a copy editor at Street Roots. Both of these are volunteer, so I’m seeking part-time work to supplement Social Security. I’ve also done everything possible as a local literary odd-jobber.

There was a time it looked like I could write poetry and be cool, but it came and went. I would have loved to have girls hanging off me. I might have hoped for more gold and more glory. There hasn’t been much of either. Boo fucking hoo. There’s always the satisfaction of doing something well. There’s also a mountain of unpublished/unread work.

What are you working on now? Doing translations, writing blurbs, copyediting at Street Roots

Walt Curtis

78, born in Olympia, grew up in Oregon City and used to take the electric trolley to Oaks Park or into Portland; cofounded the Oregon Cultural Heritage Commission; has collaborated with filmmakers Penny Allen, Bill Plympton, and Gus Van Sant; works include Mala Noche and Peckerneck Country

I was at Oregon City High School, where the newspaper was called the Elevator. My English teacher Mrs. Wade loved my writing. She got me really charged up. I was in the Honor Society. I read Dostoevsky. My mother probably got me started by reading fairy tales. I was inspired by Kerouac and Ginsberg. Going to Portland State happened. I took a speech class. I was shy, trembling in my boots. But as soon as I started talking, I realized I had power.

I was the loneliest bastard in the world in Oregon City. I was afraid to be a gay. I thought I would ruin people’s lives with my gayness. I thought I was an aberration instead of a variation.

The voice is all we have. Words can reshape the world. The Beats opened up language, made me realize I could say anything I wanted. And I should say everything I needed to say. The first small book, Angel Pussy (named for a dog that belonged to an always-armed landlady), came out. And then The Erotic Flying Machine. They were about revolution and sexuality. Poets have to have a hunger for self-expression. But it’s also a dialogue with others. Poetry is a dialogue. It has to be a dialogue. It’s got to go back and forth. A poet has to be able to listen.

Is poetry important? Poetry is the voice of the earth.

**Meet some of these poets and hear their work at a reading at Ford Food + Drink on Monday, December 2, at 6:30 p.m.