A New Exhibition Wrestles with the Meaning of Monuments

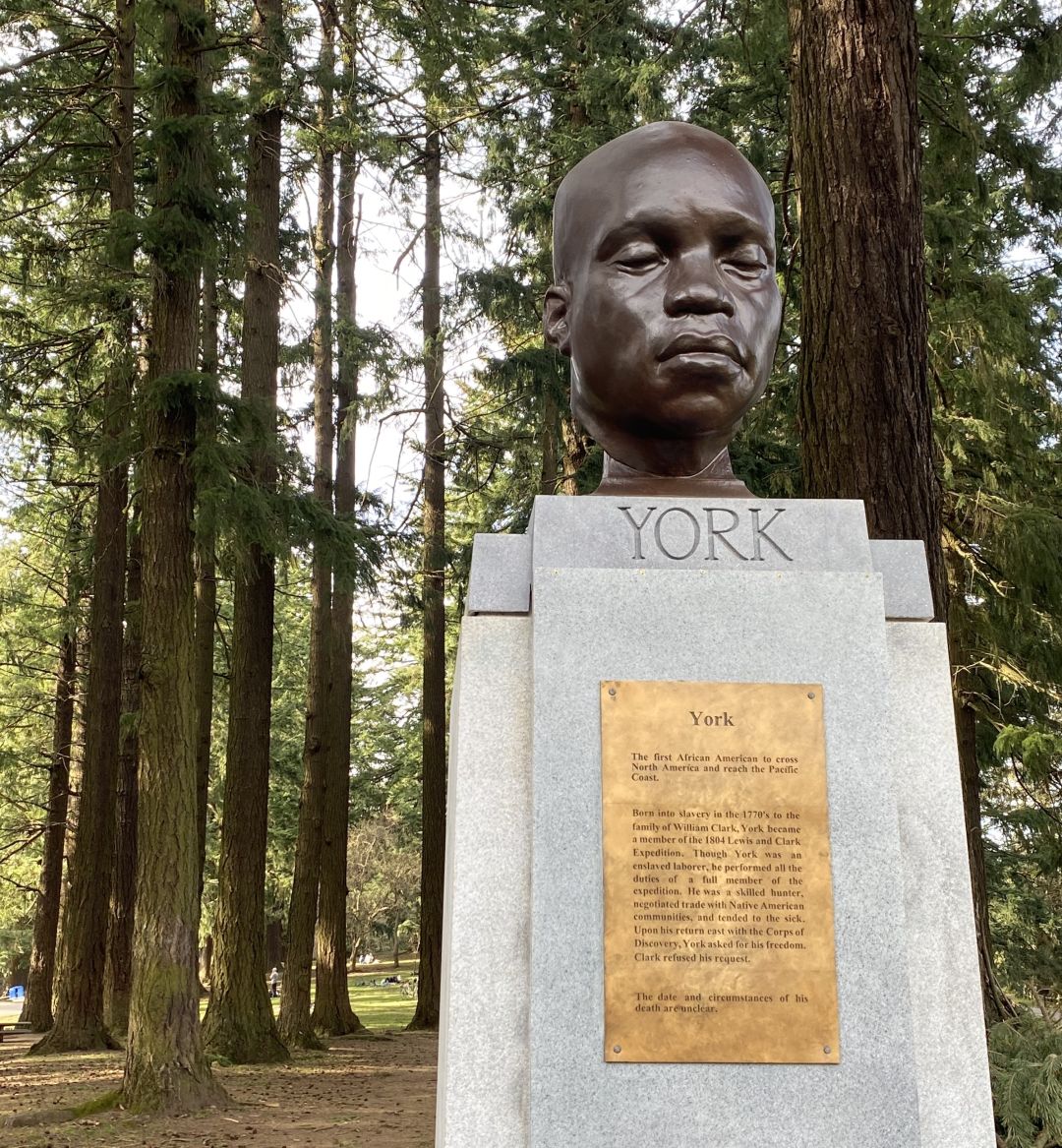

The recently toppled York bust on Mt Tabor

Image: Conner Reed

What should a monument be? It’s always been a big question; it’s gotten bigger in the last year and a half. After statues depicting a slew of historical figures started falling worldwide amid last summer’s racial justice protests, Portland received special attention, both from the press and the then-president.

A sculpture of York, the enslaved Black man who accompanied Lewis and Clark on their journey west, replaced one of right-wing former Oregonian editor Harvey Scott on Mt Tabor in the fall (and then got toppled last month). Pedestals that once held the likenesses of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson still sit empty. So where do we go from here?

That's the question Prototypes, a new exhibition from Converge 45, poses. A part of the organization's ongoing Portland Monuments and Memorials Project, which to date has hosted four discussions and a film festival themed around the subject of monuments, Prototypes will present work by more than 30 artists that attempts to wrestle with a monument's place in the modern world and chart a path forward after a year of fiery debate around the topic.

"It's helpful to have programming that allows for conversation," says Jess Perlitz, head of sculpture at Lewis & Clark College and co-developer of Prototypes. "I don't know that programming actually needs to provide an answer."

Perlitz was approached by Converge 45's executive director Mack McFarland (who also serves on the Regional Arts and Culture Council's public art committee) last October to help him get his head around what eventually became the Portland Monuments and Memorials Project. It was early in his tenure at Converge 45, and he wanted to generate programming at a time the city was mostly void of it. "It seemed so important that it be something of the time," McFarland says. "Like, really getting into something that was happening right then."

So he and Perlitz and a host of others, from artists to academics to community activists, held conversations, private and public, about what the hell a successful monument was anyway. McFarland gathered work from Northwest artists who'd been grappling with these questions well before the summer of 2020, and in March, Converge 45 held an open call for the proposal of new monuments, asking respondents to consider two questions: 1) What is an appropriate monument for this time and place? 2) What monuments or memorials would you want in your neighborhood?

"We've been rereading [the responses] lately," McFarland says, identifying a pair of through lines. "There's a real desire to display other types of history: historical moments that occurred and are little-known or glossed over—everything from the individuals who were on this land before the process of settler colonialism and slavery, to a miner strike that occurred, to apple orchards that used to fill the Kenton neighborhood.... And also some more tongue-in-cheeky things that are relevant to this moment, like a proposal to create a monument to the common lab rat."

Prototypes compiles responses from that open call and presents them beside pieces that meditate on the role of monuments in general (including a piece by Perlitz herself). It will go up on August 25 in a 5,000 square-foot vacant space at 1010 NW Flanders, and remain open through October 9.

Two pieces will come from submissions created by the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde: "Traveling with Our Ancestors," which honors Indigenous links to the Willamette River, and "First Fish Herons," a series of plinths that echo Clackamas celebrations of Chinook Salmon runs.

"For a lot of people, the Indigenous names of the people of Portland are their own names, right? Clackamas, Cascades, Multnomah," says David Harrelson, manager of the cultural resources department at Grand Ronde. "And while people are familiar with the names, there really lacks an understanding of what sort of visuals are associated with those people: the art form, what they looked like, their cultural practices. Both of these projects fill that in."

When he saw Converge 45's open call on RACC's social media, rather than reach out to a single artist, Harrelson assembled colleagues at Grand Ronde who work in various strains of the visual arts to help draw up a response. "From the tribal perspective of being a Native person from this place, [proposals] are well-suited to being from communities instead of individuals," he says. "But I think that a lot of the way monuments are framed are not from a group place, but from an individual artist and an individual idea."

Rather than settle conversations they describe as "polemic" and "combative," Perlitz and McFarland hope Prototypes provides 5,000 square feet of space for people to let them marinate.

"My hope is that, when people come away from [this exhibition], that polarized conversation of, ‘This needs to come down,’ or ‘This needs to go up in its place,’ or ‘This must stay,’ and this deep anxiety around change, becomes more nuanced and can hold all the difficulties and complexities of that conversation," Perlitz says. "And maybe we can really think about what's so scary and difficult about change. Or we can struggle with what we're holding onto, and we can talk about what might be wrong with that, or what might be powerful with that."