The Best Oregon Books of 2021

Image: Katie Leimbach

2021 was as good a year as any to disappear into a book. While rules changed and goalposts moved and we all adjusted to new versions of "stability" every five minutes, it was soothing to slip into worlds that anchored us in place, however briefly. Plenty of Oregon writers stepped up to the plate, offering up humor, pathos, sweeping historical fictions, intimate local ones, and even some perspective on the still-roiling pandemic that consumed so much of our focus. Without further ado, these were our favorite Oregon books of 2021.

Beasts of a Little Land by Juhea Kim

Image: ecco

It is not common to open a book from a Portland writer and find yourself in the mountains of Korea, at the beginning of the 20th century, tracking a tiger. But Juhea Kim is an uncommon writer, and her debut novel, Beasts of a Little Land, is a vast, ambitious saga spanning generations and geographies that couldn’t feel farther from the present-day Pacific Northwest she calls home. It follows a series of interconnected characters in Japanese-occupied Korea—a Japanese soldier, an apprentice courtesan, a street urchin, a rickshaw driver—to the country’s ultimate independence and subsequent division. But though it unfolds against this historical backdrop, Beasts of a Little Land is as much a story of love—requited, unrequited, imperfect, fleeting, dogged, romantic, platonic, familial—and the knocks of time on our bodies and spirits as it is about a moment for one country struggling against colonialism. In Kim’s deft hands, it becomes an epic tale of human connection over a lifetime and a lyrical portrait of the land they all call home. —Fiona McCann

Born on the Water by Nikole Hannah-Jones and Renée Watson; illustrated by Nikkolas Smith

Image: Kokila

Portlander Renée Watson teamed up with renowned journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones (herself a former Oregonian reporter) for this dive into the history of a Black girl who cannot trace her family tree beyond three generations. Through a series of lyrical but accessible poems, her grandmother takes her back to their West Central African origins, where her ancestors had a language and culture and skills with the land and with each other. The story moves from bright pages of their joyous origins to dark, evocative illustrations as her ancestors are stolen and transported across the ocean with people from other villages. Born on the Water is ultimately a story of hope, resistance, and the legacy of all of those who came before, a "proud origin story” brought to life with vivid images by artist Nikkolas Smith. —FM

Crying in H Mart by Michelle Zauner

Image: Knopf

The Eugene-raised Japanese Breakfast frontwoman leaves it all on the table—proverbial and otherwise—in this gutting literary debut. From the fantastic opening line, you know where everything’s headed: Zauner’s mother died of GI cancer when Zauner was 28, and a significant chunk of H Mart recounts the harrowing experience of caring for a parent while they dwindle before your eyes. What makes the book so special, though, is the way it renders the joy in the margins of that experience—the new connections to old memories, the shared meals, the sudden floods of compassion—not to mention its remarkably clear-eyed portrait of Zauner’s late mother as a flawed, full person. It's a book about grief that finds room for laughter, a book about food that finds room for tears, and an unfair article of proof that sometimes great songwriters are also great memoirists. May it be an auspicious start to a long literary career. —Conner Reed

Easy Crafts for the Insane by Kelly Williams Brown

Image: G.P. Putnam's Sons

Taking a page from Nora Ephron’s Heartburn, Kelly Williams Brown—the Salem-based writer who (ambivalently) coined the term “adulting”—decided to spin the worst two years of her life into a cheeky instruction manual. Easy Crafts is a funny, sharp-tongued memoir about Brown weathering a torrent of tragedies, winding up in inpatient psychiatric care, and coming out the other side; it's also a crafting book, punctuated with instructions for making making paper stars, origami lights, charm bracelets, and the like. The crafts echo Brown's personal tumult, and many coincide with the self-soothing she was doing, say, after her marriage ended, or she broke her arm, or her father got sick, or or or. Gluing it all together is her irreducible voice, determinedly light in the face of immense darkness, which mimics the exhilaration you feel when your fast-talking friend cracks themselves open over a few drinks and you get to glimpse their raw, one-of-a-kind, blood-spattered heart. —CR

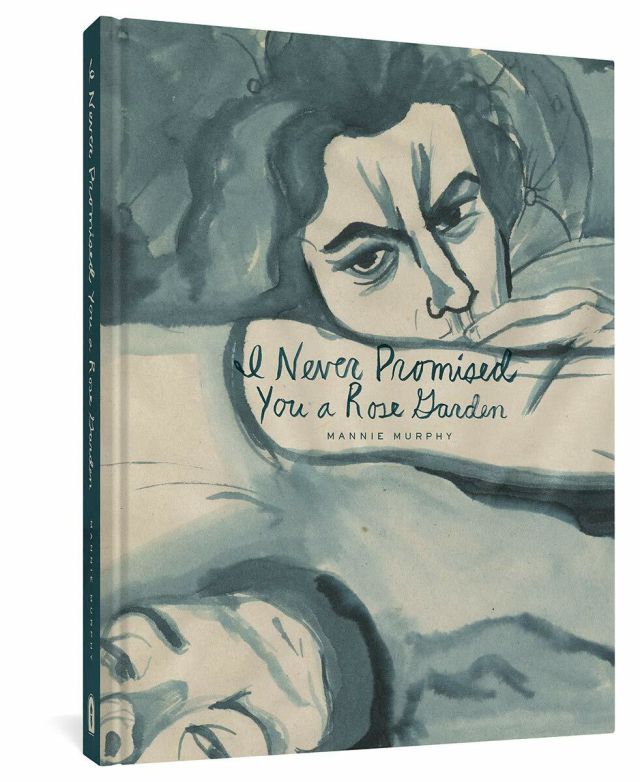

I Never Promised You a Rose Garden by Mannie Murphy

Image: Fantagraphics

In greyscale ink washes, genderqueer artist Mannie Murphy unearths a hidden history of Portland. Reflections on the death of River Phoenix and My Own Private Idaho give way to tales from Portland’s gay underground in the 1990s, from street hustlers to skinheads. Coloring it all are the enduring legacies of white supremacy and patriarchal power in the Rose City’s history, but this graphic novel, presented almost like diary entries on water-stained lined paper, evokes the ways celebrity culture and historic injustice can feel achingly personal. —Karly Quadros

Lovability by Emily Kendal Frey

Image: Fonograf Editions

The Oregon Book Award-winning poet's latest collection (following 2014's Sorrow Arrow, which clinched her that award), is a startling, mercurial meditation on the ways we kiss and kill each other. Images appear, transform, fade, and return, prodding us to reconsider our fixed relationships to the world around us. The sprawling "I Became Less Acceptable to Those in Power" lays out the goal, if you can call it that, which is to demolish hangups about whether we deserve—full stop. It could be trite, but in Kendal Frey's hands, it's the furthest thing from it: she keeps things disorienting, disarming, and as a result, divine. —CR

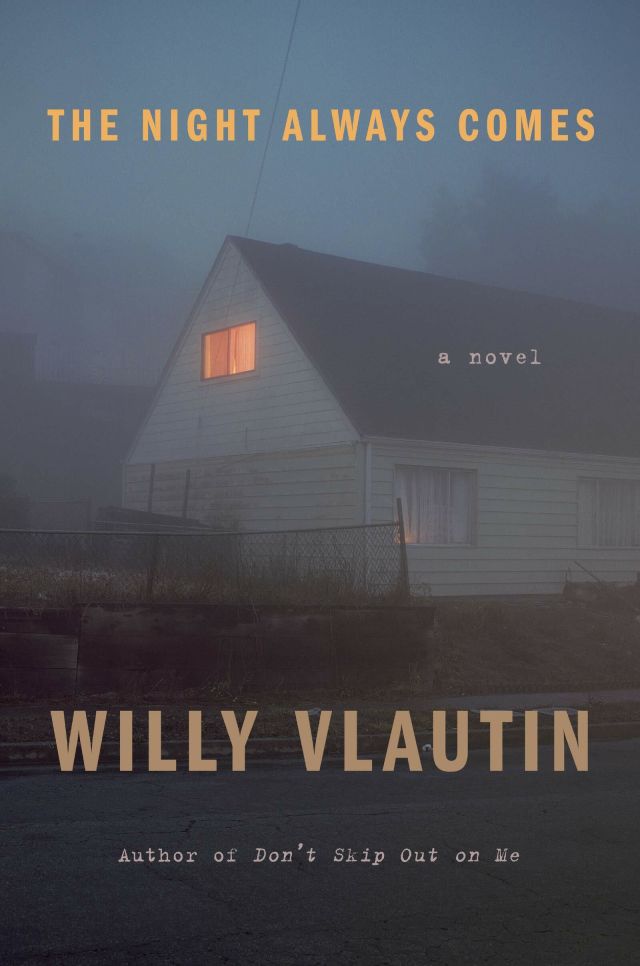

The Night Always Comes by Willy Vlautin

Image: Harper

The sixth novel from Portland musician and writer Willy Vlautin is unsparing in its depiction of the grim realities of financial struggle and loneliness. It’s the story of 30-year-old Lynette, who works multiple low-wage jobs while caring for her developmentally disabled brother and struggling to keep her head up in a PCC accounting course. She’s saving to buy the crumbling house she lives in with her family, knowing that the alternative is to lose it and any chance of owning her own place in a rapidly gentrifying city. In Lynette’s way are bad credit and a mother who has given up on trying, their combined forces pushing her off the licit path towards a slew of grifting and desperate characters. It’s a grim portrait of those our city constantly leaves behind, and a reminder of how much worse off it is as a result. In the end, Portland’s loss may well be Lynette’s gain in a searing and deeply human novel that allows her some kind of way out even as the traps close all around. —FM

Voices from the Pandemic by Eli Saslow

Image: Doubleday

“Up until a few weeks ago, I was the anesthesiologist people would see when they were having babies.” That’s Cory Deburghraeve, speaking as the intubator in a Chicago ICU in April 2020, 14 hours a day, six days a week. “They keep telling me it’s not my fault, and I’d give anything to believe that,” says Francine Bailey, after passing COVID-19 to her mother. “We’re at the mercy of the virus. We sit here and wait,” says Bruce McGillis, a nursing home resident in Ohio. These and more testaments to a year of heartbreak, loneliness, loss, and courage—27 in all, from a coroner burying his own friends to a grandmother being evicted to a young woman 287 days into long COVID—are collected in Portlander Eli Saslow’s Voices from the Pandemic: Americans Tell Their Stories of Crisis, Courage and Resilience. It’s a rich and deeply human document of the pandemic’s extraordinary toll on all of us that somehow turns the page toward hope. —FM

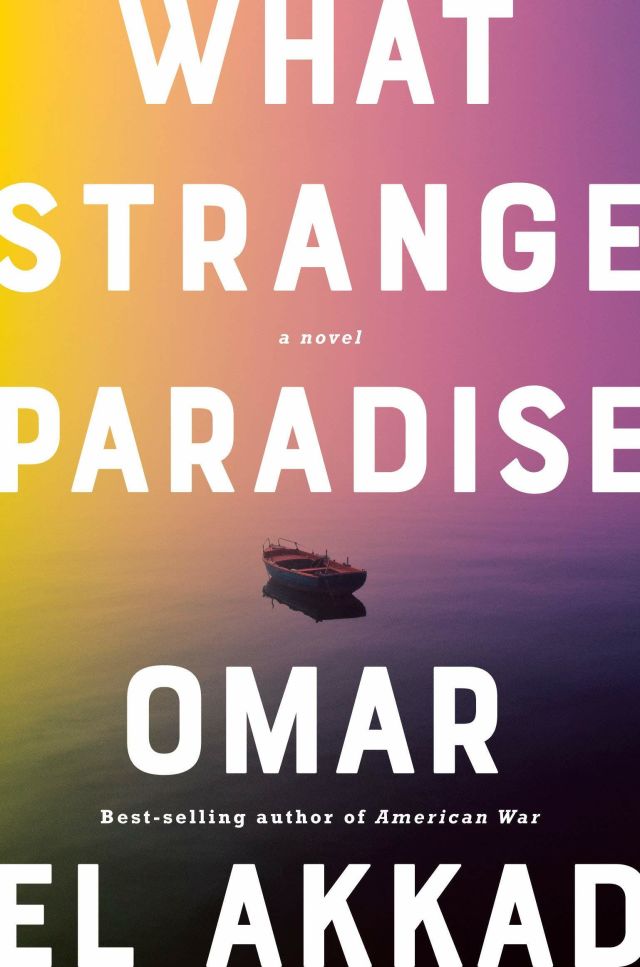

What Strange Paradise by Omar El Akkad

Image: Knopf

A former reporter covering Afghanistan, Guantanamo, and the Arab Spring for The Globe and Mail in Canada, and the author of speculative dystopian epic American War, Omar El Akkad provides unflinching but always compassionate looks at the most vast and destructive conflicts of our era: war, scarcity, exploitation. What Strange Paradise, his second novel, chronicles the odyssey of Amir, a 9-year-old Syrian refugee washed ashore on a Greek island after a shipwreck, and 15-year-old Vänna, a Nordic girl who shelters him. Flickering back and forth between Amir’s life before and after the shipwreck, the novel follows this tender and unlikely duo as they grapple with language barriers, nationalism, and liberal indifference. —KQ